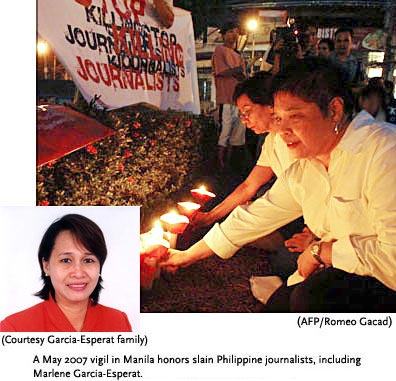

Marlene Garcia-Esperat is among dozens of reporters murdered in the Philippines. Unlike all the others, though, her case might actually be solved.

MANILA, Philippines

Marlene Garcia-Esperat was an accidental journalist. A chemist for the agriculture department on the southern island of Mindanao in the early 1990s, she was scrounging to equip her laboratory when she discovered her unit was receiving just 40 percent of the funds the government had supposedly allotted. When she set out to investigate, she found a system so ridden with graft that officials were pocketing millions from government contracts as poor farmers went without seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides.

Enraged by what she learned, Garcia-Esperat used the antigraft provisions in Philippine law that allow citizens to file corruption complaints in court. She gave testimony at trial and even served as the agriculture department’s ombudsman for a time. But antigraft prosecutions can move slowly, and those she had charged were well connected enough to drag out and manipulate the process.

Impatient for results, Garcia-Esperat turned to reporting. She exposed the corrupt deals in a program she hosted on Radio Natin and in a column called “Madame Witness” for the Midland Review in Tacurong, a small city set amid cornfields in the island’s heartland. Expanding her scope, Garcia-Esperat went on to document a string of corruption allegations against high-ranking officials in both Mindanao and Manila. In a country where guns proliferate and the justice system is compromised, hers was risky work.

On March 24, 2005, as Garcia-Esperat was having dinner with her two sons, a man walked into her dining room, greeted her with a “Good evening, ma’am,” and pulled out a .45-caliber pistol. He shot her once in the head. She was 45.

Audio Slide Show: Elisabeth Witchel discusses CPJ’s campaign against impunity in journalist murders.

CPJ’s database of all journalist deaths worldwide since 1992.

At least 32 Philippine journalists, including Garcia-Esperat, have been killed in direct relation to their work since 1992, the year CPJ began compiling detailed research on journalist deaths worldwide. While the country has a vibrant press that takes its watchdog role seriously, it is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a reporter. In Manila and other big cities, the media are able to work freely, but in out-of-the-way places like Tacurong, lawlessness and a culture of impunity mean that journalists put their lives on the line.

Garcia-Esperat’s case could have been like so many of the others in the Philippines, unsolved and ultimately forgotten. But her killing outraged local and international journalists, who launched intensive campaigns to bring attention to the case. The government, facing rising criticism for ignoring violence against the press, devoted national resources to ensure a thorough investigation. A gutsy private lawyer agreed to help prosecute, witnesses were given some protection, and the trial was moved to an impartial venue.

In October 2006, the gunman and his two lookouts were sentenced to life terms—making the Garcia-Esperat case, according to CPJ research, one of only two in the Philippines since 1992 in which the murderers of journalists have been convicted.

In October 2006, the gunman and his two lookouts were sentenced to life terms—making the Garcia-Esperat case, according to CPJ research, one of only two in the Philippines since 1992 in which the murderers of journalists have been convicted.

Now, the two officials said to have ordered the killing may also face trial. Incredibly, in the 15-year period analyzed by CPJ, no mastermind has been convicted in the slaying of a Philippine journalist. The Garcia-Esperat case, advocates believe, may serve as a map for justice in even the most intractable of places.

Worldwide, journalists have been killed in direct relation to their work more than three times per month since 1992, according to CPJ’s ongoing analysis of journalist deaths. The vast majority—about 73 percent—are not killed by crossfire during combat or while covering other dangerous assignments. They are murdered.

And most of these murders are never solved, CPJ’s analysis shows. About 85 percent worldwide have resulted in no conviction at all. In less than 7 percent of cases are both assassins and intellectual authors convicted. These sobering figures have pushed the issue of impunity to the forefront of international press freedom efforts.

“The anti-impunity battle is attracting more attention among the international press community now than it did 10 or 15 years ago,” said Juan Francisco Ealy Ortiz, who heads the Inter American Press Association’s Committee against Impunity. “There is a greater awareness on the part of journalists of how impunity and violence have reduced the ability to report and, what is even worse, have encouraged self-censorship.”

In rural Colombia, intimidation has led to journalistic silence on the murderous excesses of paramilitaries and rebels. In vast areas of Mexico, reporters have virtually stopped covering drug trafficking and other crime. And in Russia, an alarming string of unsolved killings has caused journalists to shy away from risky political topics.

Russia and the Philippines are among the very worst in solving journalist murders, and perhaps not coincidentally, they are among the world’s five deadliest nations for the press. Russia has trumpeted many arrests in high-profile cases such as the 2004 slaying of American Paul Klebnikov and the 2006 murder of Anna Politkovskaya, but it has been incapable or unwilling to see these cases through to conviction.

CPJ research suggests that countries with high impunity rates also have a higher incidence of killings. “Impunity is a chronic disease,” said Karen Nersissian, a lawyer representing the families of three slain journalists in Russia.

|

The Private Prosecutor

As a private attorney in the Philippines, Nena Santos does not have standing to try a murder case … » by Joel Simon |

Marlene Garcia-Esperat had received so many threats, her murder seemed inevitable to her family and friends. Unfazed by the risk, she was fond of saying that she had been reared on bullets. Garcia-Esperat grew up in Mindanao, in a dusty plains town settled by Christian migrants who came to live in the country’s Muslim south after World War II. Her father was a local police chief who survived two assassination attempts. Her first husband, Severino Arcones, an outspoken broadcaster for Bombo Radio, was killed by an assassin in 1989.

She was targeted too. One failed 2001 assassination plot led to an arrest. “When the police searched his belongings,” Garcia-Esperat recounted in an interview that year, “they found a picture of me, with my name and address and an X mark at the bottom of my picture.”

Garcia-Esperat requested police protection after a third attempt on her life that year, but she still pursued high-profile investigations, including one that sought to link officials close to President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo to a multibillion-peso scam involving government fertilizer purchases. Throughout, she focused much of her journalistic energies on the same agriculture department that first sparked her outrage, an agency known as one of the best-funded and most graft-prone in the government. Her journalism earned her a reputation for integrity and courage.

It did not earn her much money. She bankrolled her crusades by selling Tupperware, running a small sundries shop in her home, and renting the motorized tricycles that are ubiquitous in rural Philippines. She earned another 18,500 pesos (US$400) a month working in a government auditing office, which employed her after she left the agriculture department.

Like many of her friends, I remember Marlene as a woman with a sharp mind, short skirts, and low necklines. My colleagues and I called her “Erin Brockovich,” after the legal clerk whose work on a major U.S. negligence lawsuit was made famous in the 2000 film. She had the sartorial style of the film heroine and the same in-your-face grit. Funny, tough-talking, and street-smart, Marlene could recite from memory the names and phone numbers of government officials—and, with little prompting, the list of charges and evidence she had filed against them. Once, she visited my office at the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism decked to the nines, her jet-black hair dyed a light brown, her eyes decorated with glitter. “I want to look pretty when the assassins come to get me,” she said.

If you’re looking for the answer to why impunity exists, first ask, Who? Who are the journalists being killed? Who are the suspects? CPJ’s worldwide analysis shows that more than 40 percent of victims had covered corruption or politics. Another 14 percent had reported on human rights violations. All of these topics are likely to inspire the wrath of powerful political and social actors.

“It’s those journalists who work on sensitive subjects who are under attack,” said Nersissian, the Russian lawyer.

Though most cases are unsolved, CPJ’s analysis of publicly available documents reveals a correlation between a victim’s beat and the potential perpetrator. In more than a third of journalist murders, CPJ found evidence that the killings were likely orchestrated by people connected to governments—elected and appointed officials, and members of the military and government-backed paramilitary groups. And when government officials are corrupt, said Nersissian, “they have the power and the ability to impede murder investigations.”

Though most cases are unsolved, CPJ’s analysis of publicly available documents reveals a correlation between a victim’s beat and the potential perpetrator. In more than a third of journalist murders, CPJ found evidence that the killings were likely orchestrated by people connected to governments—elected and appointed officials, and members of the military and government-backed paramilitary groups. And when government officials are corrupt, said Nersissian, “they have the power and the ability to impede murder investigations.”

Witness intimidation is a particular scourge. Two witnesses were killed and a third nearly gunned down before the case of slain Philippine broadcaster Edgar Damalerio could reach trial. In 2005, a police officer was finally convicted of the 2002 shooting–one of the rare victories in the Philippines–but the prosecution did not reach those said to have ordered the killing.

Impediments can be societal as well, such as dysfunctional justice systems and a lack of police and prosecutorial resources. “Impunity has its roots in weak judiciaries, weak or nonexistent legislation, political neglect and lethargy, inadequate training of reporters on risks and security issues, little solidarity among media and journalists, and a lack of public awareness as to what the murder of a journalist means,” said Ealy, the impunity director for the Inter American Press Association.

Garcia-Esperat’s assassins arrived during the Easter holidays, when normal life in the predominantly Catholic Philippines grinds to a halt. She had told her police bodyguards to take a few days off and spend some time with their families. That week, as she was home alone with her children, contract killers put her under surveillance and waited for a time to strike.

The three men who murdered Garcia-Esperat were professional assassins who based their fee on the prominence of the target and the difficulty of execution. As evidence presented at their trial showed, they were paid just a little more than 100,000 pesos (US$2,700). Garcia-Esperat, they said, was not “big-time” and so did not command a high price. They were certain they could get away with the crime, having little reason to think that killing a reporter would shock so many.

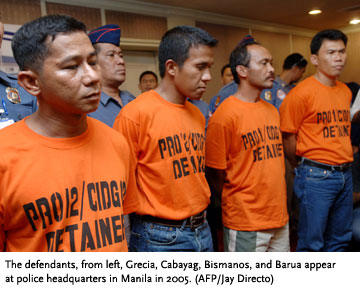

The killers–later identified as Gerry Cabayag, Randy Grecia, and Estanislao Bismanos–monitored the journalist’s movements and routines. They bought cigarettes at the family’s sundries shop, which was attached to the Garcia-Esperat home, and befriended the journalist’s children, who often minded the store. They played chess with Garcia-Esperat’s 13-year-old son, Kevin, and got pedicures at the salon next door.

On March 24, Maundy Thursday, the men visited the store several times on the pretext of buying cigarettes and “loads,” or minutes, for their cell phones. Grecia returned to the store in the late afternoon and stayed long enough to see Garcia-Esperat preparing to have dinner with her family. According to court documents, he sent text messages to his companions to say that their target was home and would be there for some time.

Shortly after 7 p.m., Cabayag went into the store and asked Garcia-Esperat’s daughter, Rynche, 23, for a cigarette. As she turned to get one, Rynche testified, Cabayag bolted into the house and, within moments, the pop of a gunshot could be heard. Kevin, who was at the dinner table with his brother, James Derek, when their mother was shot, recognized Cabayag as one of the men who had been at the store in previous days. The boy chased Cabayag, but the gunman hopped aboard a motorcycle with Bismanos and roared off.

The killers were so brazen, they left plenty of clues. Police quickly traced Grecia’s identity through his cell phone, and he, in turn, identified his accomplices. Nine weeks later, as police amassed further evidence, the hit men confessed to their roles in Garcia-Esperat’s death and said they had been hired by a military intelligence officer named Rowie Barua.

Barua told investigators, and later testified in court, that he hired the killers at the behest of Osmeña Montaner and Estrella Sabay, two regional agriculture department officials whose dealings Garcia-Esperat had investigated for years. Montaner was finance officer for the department’s central Mindanao office; Sabay was the regional accountant.

Garcia-Esperat had identified the two as being at the hub of departmental corruption, and outlined detailed allegations that they had skimmed millions from government contracts. She accused them of once burning down the department’s regional office to destroy evidence of corruption.

On October 7, 2006, after a six-month trial, the three hired assassins were sentenced to life imprisonment. Barua, the middleman, was acquitted after testifying for the prosecution. Despite Barua’s detailed testimony implicating Montaner and Sabay, Judge Eric Menchavez declined to indict the two men, citing a lack of jurisdiction. Calls placed by CPJ to Montaner and Sabay were disconnected after a reporter requested comment. Subsequent calls by CPJ went unanswered.

T he Garcia-Esperat case stands apart in several ways.

he Garcia-Esperat case stands apart in several ways.

Wide publicity–including heavy news coverage and intensive advocacy by press groups such as CPJ–insulated the case from political pressure. Public outrage spurred the national police to create a special task force. The Supreme Court allowed the transfer of the trial from a rural outpost in Mindanao to Cebu City, a provincial capital of more than 700,000 where witnesses felt they would be safe. The witnesses, including Garcia-Esperat’s children, were placed in a government protection program. The Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists, the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines, and CPJ all raised money to help pay legal and protection expenses.

Nena Santos, a lawyer and friend of Garcia-Esperat, agreed to act as private prosecutor, helping state prosecutors not only gather and present evidence but also convince witnesses mistrustful of the police and the courts to testify. The Philippine legal system allows private lawyers representing the families of victims to assist in the prosecution of criminal cases. Apart from contributing their time and expertise to the financially strapped state prosecutorial system, they provide needed oversight.

Press groups around the world are using these and other tools. Some techniques, such as the use of private advocates, are tailored to local law or custom. Others, such as trial monitoring, can be important global techniques. In Peru, the press group Consejo de la Prensa Peruana (Peruvian Press Council) sent a team of 20 journalists to the rural province of Ucayali to observe proceedings surrounding the 2004 murder of radio host Alberto Rivera Fernández. Under such watch, the prosecutor ultimately announced an intention to pursue conspiracy charges against the local mayor, according to the group’s director, Kela León.

Press groups are also making use of international bodies. Ruling in a case filed by the widow of slain Ukrainian journalist Georgy Gongadze, the European Court of Human Rights found that authorities had failed to protect the editor’s life and thoroughly investigate his death, awarding her damages of 100,000 euros (US$139,000). In Latin America, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has agreed to review 11 cases. The Inter American Press Association has been instrumental in raising such cases.

Although international bodies are often limited in their ability to order direct action, they have the effect of shaming governments. Thus, each case has the potential to cause domestic changes, said Philip Leach, director of the European Human Rights Advocacy Centre, an organization that specializes in bringing cases before the European court.

Can sustained efforts to combat impunity make a difference? The Inter American Press Association has operated its anti-impunity campaign since 1993. CPJ’s independent analysis of murder cases in Latin America shows that about 43 percent now end in arrest and prosecution, an increase from the region’s 28 percent rate in the 1990s.

For all the successes in the Garcia-Esperat case, the task is unfinished.

In September, family and press advocates met with acting Justice Secretary Agnes Devanadera to urge that prosecutors reopen the case against the two agriculture officials who allegedly plotted the murder. Top law enforcements officials, including those who met with CPJ in July, say they are receptive to pursuing the case.

Santos has persisted in the meantime, gathering evidence, drafting a potential indictment, and working with police to keep the case alive. But Santos, who has worked for free, has paid for her work: Threatened, she has had to move to Manila, accept police protection, and leave behind her Mindanao law practice.

“There was a lot of pressure on us and the public prosecutors to drop this case,” Santos said. “But it was essential for me to be there at the outset, from the gathering of the evidence, the securing of the evidence, talking to the witnesses and convincing them to testify. If I left it to the police, they may not have been able to get enough evidence and the case could be open to manipulation. The police and the state prosecutors have to know that there’s oversight of the case, and the possible consequences if they messed around with it.”

Her sacrifice, she said, is small compared to that of Garcia-Esperat’s children, who saw their mother murdered, lost their everyday lives to witness protection, and endured the fear and anxiety of testifying at trial. “All they want is to see justice for their mother,” Santos said. “We have to get the others.”

Sheila Coronel, a CPJ board member, is a veteran Philippine journalist who now heads the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia University. Elisabeth Witchel, CPJ’s impunity campaign coordinator, reported from New York. CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon and Europe Program Coordinator Nina Ognianova contributed to this report.

« Return to Main Menu: The Road to Justice