At least three journalists a month flee their home countries to escape threats of violence, imprisonment, or harassment. By Elisabeth Witchel and Karen Phillips

Posted June 19, 2007

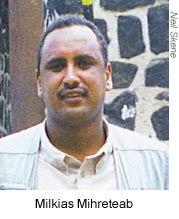

Nearly six years ago, Eritrean authorities raided the offices of the country’s private newspapers, shut them down, and detained at least 10 journalists. Tipped off by friends, Milkias Mihreteab, then editor-in-chief of the  independent weekly Keste Debena, went into hiding, narrowly escaping arrest. He began a harrowing journey on foot across local borders before securing passage to the United States, where he eventually was granted political asylum.

independent weekly Keste Debena, went into hiding, narrowly escaping arrest. He began a harrowing journey on foot across local borders before securing passage to the United States, where he eventually was granted political asylum.

Since coming to the United States, Mihreteab has worked a variety of jobs, including as a coffee shop server and a security guard, but none related to journalism. He attempted to launch a new version of his paper for other Eritrean expatriates but couldn’t afford to keep it going. He has watched his once ardent hope of returning home within a few years wane, as more than a dozen publishers and editors continue to languish in prison in Eritrea today. Mihreteab still wants to go home, but the prospect is not imminent.

His is one of 243 cases of journalists forced into exile that the Committee to Protect Journalists has documented over the past six years.

Among the key findings: At least three journalists a month flee their home country to escape threats of violence, imprisonment, or harassment; more than two-thirds of the 209 journalists currently in exile have not found opportunities to continue in their profession; and only one in seven journalists who flees ever returns home.

Joel Simon, CPJ’s executive director, deplored the conditions that have led to the exodus of journalists in so many countries and called on governments to do the following: investigate and offer protection when journalists are assaulted or threatened; prosecute all parties when a journalist is murdered; cease unlawful arrests of journalists; and reform criminal defamation laws.

“The fact that in two out of three cases, the exiled journalists were driven out of the profession altogether, only finishes the job of those who seek to silence the press,” Simon said.

CPJ began tracking journalists in exile with the launch of its assistance program in July 2001. The program helps journalists in dire situations as a result of their work, including those who need to go into hiding or exile to escape threats.

CPJ began tracking journalists in exile with the launch of its assistance program in July 2001. The program helps journalists in dire situations as a result of their work, including those who need to go into hiding or exile to escape threats.

CPJ limited its survey to those individuals who research determined had fled persecution for their work as journalists, and whose whereabouts, status, and current activities were known. The survey does not include dozens of journalists and media workers who left their countries for professional or financial opportunities, or individuals who fled their homelands before July 2001. The survey also does not include journalists who may have been targeted for activities other than journalism, such as political activism.

The survey found that the leading reason journalists flee their homelands is the threat of violence, followed by imprisonment or threat of imprisonment, and harassment.

CPJ determined that 94 journalists fled their homelands after violent assaults or death threats from fundamentalist militias, paramilitaries, and political gangs. In some cases, they heeded ominous warnings from military or government officials. The worst offenders in this category were Colombia, Haiti, Afghanistan, and Rwanda, where, according to CPJ research, 50 journalists went into exile at some point during the survey period in fear of violent attack. In many cases, authorities could not or would not provide adequate protection for journalists, and attempts to relocate within their countries did not bring an end to the threats.

Colombian investigative reporter Jenny Manrique moved from Bucaramanga province to Bogotá in 2006 after receiving a steady stream of death threats in response to her reporting on paramilitary abuses in the region. But the threats didn’t stop. Manrique finally left Colombia with the help of regional and international press freedom organizations, including CPJ.

Colombian investigative reporter Jenny Manrique moved from Bucaramanga province to Bogotá in 2006 after receiving a steady stream of death threats in response to her reporting on paramilitary abuses in the region. But the threats didn’t stop. Manrique finally left Colombia with the help of regional and international press freedom organizations, including CPJ.

“When I learned that the people who were harassing me had located my house in Bogotá and they made threatening calls that put my loved ones at risk, I decided that it was time to do what they’d been ‘requesting’ me to do for the last eight months: shut up. I had to leave the country,” Manrique told CPJ.

In the other cases, 76 journalists fled upon their release from prison or under threat of imprisonment for their work, and 73 left after enduring sustained harassment.

The 243 journalists surveyed by CPJ came from 36 countries, with more than half hailing from just five: Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Colombia, and Uzbekistan. Sixty percent were from African countries, where porous borders and harsh press freedom conditions contribute to a steady exodus of journalists.

North America, Europe and Africa host the most journalists in exile, with the United States, Britain, Kenya and Canada ranking as the top four countries of refuge in the CPJ survey.

Nearly three-quarters of the journalists currently in exile landed outside their region; 123 sought and obtained asylum on their own or were resettled by the U.N. High Commission for Refugees. At least three dozen ended up in neighboring countries, in many cases unable or not permitted to find work. Most of those are living in extreme poverty, and some have been harassed by police who routinely shake them down, threatening to send them to refugee camps or report them to officials in their home countries.

Over the period surveyed, 34 journalists who had gone into exile eventually returned home when conditions seemed safer for them. Of those who returned, 86 percent resumed work in journalism, either in their former positions or in comparable jobs. This is in sharp contrast to the journalists who remained in exile: Just 30 percent were able to obtain jobs related to journalism (a category that includes teaching), though larger numbers have continued to contribute sporadically to expatriate media or media outlets in their homelands. The vast majority, however, have had to take jobs requiring a lower level of skills.

Pakistani journalist Majid Babar has been working in a gas station in the United States since getting asylum in 2004. He fled Pakistan the previous year after being harassed by authorities for working with foreign correspondents covering terrorism.

Pakistani journalist Majid Babar has been working in a gas station in the United States since getting asylum in 2004. He fled Pakistan the previous year after being harassed by authorities for working with foreign correspondents covering terrorism.

He can’t find work as a journalist even though he spent his first year in the United States as a Humphrey Fellow in Journalism at the University of Maryland and has kept in touch with members of the U.S. media with whom he worked in Pakistan.

“Although I have so many friends in the mainstream media here in the United States … I can’t get any job with these media, because I am no longer considered a journalist,” Babar told CPJ. “I am just one among the millions of refugees.”

Forward Maisokwadzo, coordinator of the Exiled Journalists Network,which supports journalists in exile in Britain, urged the media in host countries to provide a platform for exiled journalists to write about their experiences and to keep the spotlight on mistreatment of the press.

“They can open their doors to journalists who have faced persecution,” he said.

Elisabeth Witchel is CPJ’s Journalist Assistance Program Coordinator and Karen Phillips is the Journalist Assistance Program Associate.

|

JOURNALISTS IN EXILE

|

|

|

A STATISTICAL PROFILE

July 2001 – June 2007 |

|

| Total who went into exile in this period | 243 |

| Total currently in exile | 209 |

| Total who have returned from exile | 34 |

|

MAIN REASONS FOR GOING INTO EXILE

|

|

| Threat of violence or death | 94 |

| Likelihood of imprisonment | 76 |

| Harassment | 73 |

|

THE 10 COUNTRIES THAT HAVE FORCED

THE MOST JOURNALISTS INTO EXILE |

|

| Zimbabwe | 48 |

| Ethiopia | 34 |

| Eritrea | 19 |

| Colombia | 17 |

| Uzbekistan | 16 |

| Haiti | 14 |

| Afghanistan / Liberia | 10 |

| Rwanda | 9 |

| The Gambia | 6 |

| Iran | 5 |

|

MAJOR HOST COUNTRIES FOR EXILED JOURNALISTS

|

|

| United States | 72 |

| United Kingdom | 24 |

| Kenya | 21 |

| Canada | 20 |

| Southern Africa (South Africa, Botswana, Zambia) | 14 |

|

PROFESSIONAL STATUS

|

|

| Exiled journalists currently in media-related jobs (including academia) | 64 (30%) |

| Journalists who returned from exile currently in media-related jobs | 30 (88% ) |