Dangerous Assignments

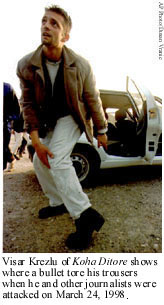

Last spring, the Committee to Protect Journalists began to document a steady stream of attacks on reporters covering the civil strife in Kosovo. Serb forces and the partisans of the Kosovo Liberation Army alike harassed foreign correspondents in the field and made it virtually impossible for local journalists to report on the civil war that would decide the future of

their homeland.

In October, as Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic faced the threat of NATO air strikes to curb his assault on the Kosovars, he resorted to time-worn tactics for stifling scrutiny of his nationalist agenda: suppression of Serbia’s independent media. Officials in Belgrade issued a series of escalating threats against the press, denouncing independent journalists as spies, and hinting that they would make good hostages should NATO take action. When CPJ responded with alarm to the Milosevic regime’s ominous promises to scapegoat the press, Yugoslavia’s Secretary for Information replied with a diatribe condemning the “many provocations” of the media in the Kosovo conflict and an invitation to me to join in forming the Committee to Protect the Truth.

Belgrade’s tactics switched from threats to action when the government issued a decree banning the media from spreading “defeatism, fear and panic,” and ordered a halt to the rebroadcasting of foreign Serbian-language news from the Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and British, French, and German radio services. The decree came the same week that Milosevic struck a deal with the NATO allies to avert the air strikes, and many journalists in Belgrade were convinced there was a connection. Some bitterly alleged that the West agreed to remain silent about the media crackdown, in exchange for Belgrade’s promise to pull out of Kosovo.

There is no evidence of such a bargain, but the rumor bespeaks the independent journalists’ despair in the face of the Western democracies’ near-silence about their plight. In solidarity with independent Serbian journalists, CPJ sent an open letter to our colleagues in Yugoslavia, expressing our alarm and condemning Milosevic’s use of the independent media as pawns in a perilous game with the Western alliance over Kosovo. We also met in Washington with Clinton administration officials, including Assistant Secretary of State John Shattuck, whose office helped generate the first public U.S. denunciation of Belgrade’s actions. Within days, the State Department had circulated another CPJ statement to U.S. ambassadors in Europe, urging them to work with their European counterparts on further denunciations of the Serb government’s attempts to silence the press.

There is no evidence of such a bargain, but the rumor bespeaks the independent journalists’ despair in the face of the Western democracies’ near-silence about their plight. In solidarity with independent Serbian journalists, CPJ sent an open letter to our colleagues in Yugoslavia, expressing our alarm and condemning Milosevic’s use of the independent media as pawns in a perilous game with the Western alliance over Kosovo. We also met in Washington with Clinton administration officials, including Assistant Secretary of State John Shattuck, whose office helped generate the first public U.S. denunciation of Belgrade’s actions. Within days, the State Department had circulated another CPJ statement to U.S. ambassadors in Europe, urging them to work with their European counterparts on further denunciations of the Serb government’s attempts to silence the press.

While Milosevic apparently remains impervious to world opinion, his KLA foes have made efforts to appear more responsive. When two Serb journalists from Tanjug, the Serbian state news service, disappeared on October 18 in Kosovo in an area where the KLA has been active, CPJ called upon the group’s leaders to investigate the disappearance and ensure their safe release. The day after we sent our letter, KLA political spokesman Adem Demaci held a news conference expressing his concern about the missing journalists. While he skirted the question of whether any of his forces were holding the journalists, he announced that he had contacted KLA headquarters to find out their account of what had happened to the pair.

We did not expect Milosevic — a master of media manipulation who is notoriously immune to international opprobrium — to loosen his grip on the flow of information. And indeed on October 20, the Serbian Parliament adopted a highly restrictive press law which formalizes the strictures of the decree. During the parliamentary reading of the law, representatives of the ruling coalition ratcheted up their accusations and threats against the independent media. Deputy Prime Minister Vojislav Seselj described independent editors as NATO officers, and referred to NATO Secretary General Javier Solana, “the man who decided on the bombing and destruction of Serbia and the killing of its citizens,” as their chief editor.

But CPJ’s advocacy has another vital purpose: To shore up the morale of our fellow journalists who are under siege from Belgrade. The principle of press freedom the independent Serb journalists are struggling to uphold undergirds all free societies. They need to know that they are not alone, and we must remind the world of the vital importance of their struggle.

Ann K. Cooper is the executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists.