Nine years ago this month, the Committee to Protect Journalists took a stand on one of the most polarizing figures in journalism. We wrote President Barack Obama and his attorney general, Eric Holder, urging them not to prosecute Julian Assange.

The Australian hacker and WikiLeaks founder was in the administration’s crosshairs for publishing classified ‘war logs’ from the U.S. military in Afghanistan and Iraq, along with diplomatic cables.

The leaks unnerved the Washington political and security establishment. Then Vice-President Joe Biden branded Assange a “high-tech terrorist” and Holder said he was considering prosecuting WikiLeaks and Assange under the 1917 Espionage Act.

We argued that wielding a blunt World War I-era legal weapon against WikiLeaks would undermine the right to gather, receive, or publish information of important public interest.

After all, if Obama prosecuted Assange, would he not also have to prosecute The New York Times, The Guardian, and other newspapers that published some of the WikiLeaks documents? That would deal a body blow to the First Amendment’s protections of free speech and the press in the United States. It would also be a gift to authoritarian leaders overseas who could cite Washington’s example the next time they wanted to jail an irksome journalist or publisher.

It was also important to defend WikiLeaks because the Department of Justice (DOJ) had already tried to accuse reporters of encouraging leaks. This happened in 2010, when the DOJ named Fox News reporter James Rosen in a search warrant as a “co-conspirator” and tracked his movements and communications.

Amid the pushback from journalists and legal scholars, no charges publicly emerged during Obama’s time in office.

But in May this year, President Donald Trump’s administration disclosed a superseding indictment against Assange under the Espionage Act and began proceedings to have him extradited from the U.K.

Assange has long been aware of the possibility of extradition. He cited fear of being taken on to the United States if he traveled to Stockholm for questioning over alleged rape and other sex crimes after accusations by two former WikiLeaks volunteers in 2010. (Assange denies the allegations). When he lost his appeal against extradition to Sweden in 2012 he jumped bail and sought sanctuary in Ecuador’s London embassy, where he remained for seven years. He was evicted in April after a change of government in Ecuador and arrested by British police. His jail term for skipping bail ended in September but he has been kept behind bars pending the U.S. extradition application. A Swedish prosecutor dropped the investigation into the rape charge this year, saying too much time had elapsed.

The charges for which Assange is now facing U.S. extradition go back at least to 2010 when Assange, working with The Guardian, The New York Times, and Der Spiegel, published the “war logs.” Among a trove of stories was U.S. helicopter video showing the Apache aircraft shooting Iraqi civilians, including two Reuters journalists.

He had begun collaborating with The Guardian as far back as 2007, but it was the dump of information to WikiLeaks from Private Chelsea Manning about the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as a quarter of a million State Department cables, that put Assange and his site on the map.

The sheer volume of material was a challenge for the three partner publications working to edit the logs and cables and redact information that could harm people mentioned in them. Assange widened the circle of editors by bringing in the newspapers Le Monde and El País.

But he grew impatient with the time it took to publish stories and dissatisfied that only a narrow range of the information he held was being made public.

In apparent frustration, he began releasing material that had not been through this journalistic process. CPJ was made aware of the dangers of this in 2011 when WikiLeaks published un-redacted diplomatic cables that endangered the life of the Ethiopian reporter Argaw Ashine.

More generally, WikiLeaks’s practice of dumping huge loads of data on the public without examining the motivations of the leakers can leave it open to manipulation, as CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon has written.

Collaboration with the newspapers over the Manning leaks became bumpy and eventually Assange fell out with the then editors of The Guardian and the Times, Alan Rusbridger and Bill Keller, respectively.

Both, however, defend him against this prosecution and believe he should be protected by the First Amendment.

“The indictment is a mish mash of accusations, including the risk of penalizing any reporter who does more than sit back and passively wait for material to be leaked to them,” Rusbridger told CPJ. (Rusbridger, now the principal of Lady Margaret Hall at the University of Oxford, became a member of CPJ’s board in 2014.)

“Assange is not my idea of a journalistic role model,” Keller, the Times’ former executive editor, told CPJ. “But he has taken no oath to protect U.S. government secrets, and I’m not aware of any evidence that he is an enemy agent, in the traditional legal meaning of the term. He gathers information (albeit sometimes by questionable methods), packages it (albeit selectively and with malice) and publishes it (albeit with no sense of responsibility for the consequences, including collateral damage of innocents.) The First Amendment doesn’t just protect people who keep honest company, uphold standards of fairness and publish responsibly.”

Trump has stopped short of prosecuting the mainstream news organizations that worked with Assange. Indeed, during the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump repeatedly said he “loved” WikiLeaks, which had published thousands of private emails that damaged his rival, Hillary Clinton. She accused Assange of colluding with Moscow. U.S. intelligence blamed Russia for the leaks.

Yet within a year, Trump’s love affair with WikiLeaks was over. In March 2017, the site published documents known as Vault 7, which showed the government’s enormous capacity to hack electronic communications. Then-CIA director Mike Pompeo, who is now secretary of state, branded WikiLeaks a “non-state hostile intelligence service.”

Assange’s U.K. defense lawyers could well use the argument that this prosecution is selective and political at the extradition hearings, a process that in any case could take years, according to some legal experts. The U.S.-U.K. extradition treaty provides for an exception of political offenses. Assange can also argue he is protected under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which guarantees freedom of expression.

Assange’s first hearing is set for February 25, 2020. Meanwhile, Assange is apparently in such bad health in Belmarsh Prison that some 60 doctors have written to the U.K. government to urge his release.

Besides the 17 charges under the Espionage Act, Assange has also been hit with a separate indictment under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Prosecutors argue that Assange conspired with Chelsea Manning to hack U.S. government computers. If successful, such a prosecution could criminalize established investigative journalistic interaction with a source, as my colleague Avi Asher-Shapiro has reported.

To some, Julian Assange is a warrior for truth and transparency. To others, he is an information bomb-thrower.

The question with which CPJ has had to grapple is whether his actions make him a journalist. Each year, we compile a list of journalists imprisoned around the world, based on a set of criteria that have evolved as technology has upended publishing and the news business.

After extensive research and consideration, CPJ chose not to list Assange as a journalist, in part because his role has just as often been as a source and because WikiLeaks does not generally perform as a news outlet with an editorial process.

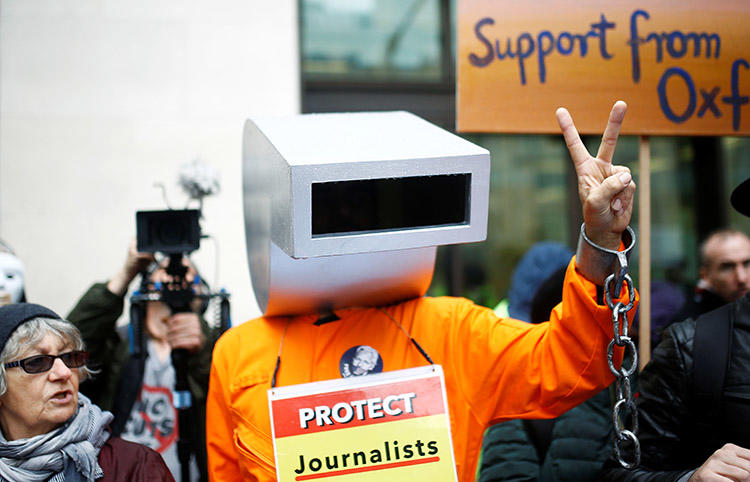

No matter what label people put on Assange, his prosecution is a threat to journalists worldwide.

Taken together, the 18 counts in the DOJ indictment criminalize key reporting practices and the publication of information obtained through them. And the extraterritorial application of the U.S. Espionage Act means that any journalist anywhere in the world could potentially be prosecuted for publishing classified information.

A successful prosecution would chill whistleblowers and investigative reporting. This is why CPJ opposes Assange’s extradition.