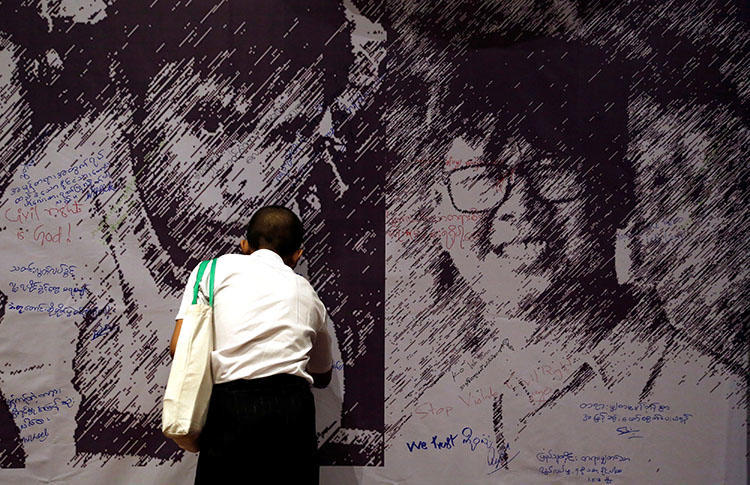

Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo have spent nearly five months in detention in Myanmar, on charges of violating a colonial-era Official Secrets Act. At the time of their arrest in Yangon on December 12, the reporters were investigating a mass killing of Rohingya men by Buddhist villagers and Myanmar troops that took place in the Rakhine state village of Inn Din on September 2, 2017, Reuters reported.

If Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo are convicted, they could face up to 14 years in prison.

In a phone interview with CPJ, Reg Chua, the chief operating officer of Reuters Editorial in New York, spoke about his colleagues, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, and why it was so important for Reuters to publish the story they had been working on.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo have been jailed for nearly five months. What are they like as reporters and how did they join the Reuters team?

You can see from Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo’s work–that great story that they did earlier this year–the kind of reporters they are. They spent months working on that. They were dogged, they went through, they checked all their facts, they tracked down not just the people in the village but people who had left the village. While they couldn’t participate actively in the editing of the story because they were in jail, the editors who went through the story found everything to be perfectly reported in the draft.

Kyaw Soe Oo is from Rakhine state. He’s someone who actually prefers poetry to journalism, but he was also in a place where he saw the sorts of things that were happening to his region and really wanted to tell the world about it. So he crossed into journalism. He joined us late last year, but he’d been reporting already in Rakhine state.

Wa Lone is a much more outgoing character. He’s been with us a couple of years now. You can see from his appearances at each of the hearings how unbowed he is by the circumstances he’s under. He always comes out and he talks about the importance of free press, the importance of democracy, and the work they’re doing. He stood up to all of this. He too has his own personal side–he’s set up a charity, written children’s books. He didn’t know when [he was arrested,] and neither did his wife at that time, that she was pregnant. They’re very happy about it, but obviously it just adds a whole extra dimension to his continued detention.

Reuters made the decision to publish the story on mass graves that Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo had been covering despite their arrest. Why was it so important to tell this story?

We had a draft of the story in at the time they were arrested. At the time, we didn’t know what was happening with them–we only found out that they were in custody a few days after they went missing, and we only found that the charges being contemplated were under the Official Secrets Act some time after that. We were editing the story while also working for their release.

Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo were both strongly in favor of publishing and that we should get the story out. Part of that is just because it was a great story and they wanted it published and part of it is obviously that it was in the public interest and in the interest of Myanmar citizens to understand what’s going on in Rakhine state. [Also,] we needed people to understand … this was the sort of work they were working on at the time they were arrested.

Myanmar has imposed reporting restrictions on Rakhine state for a long time. What impact has that had on the press and do you think the climate for press freedom in Myanmar has changed in recent years?

If you go back 10 or 15 years, when Myanmar was under military government, clearly the media environment was much worse. Things have, without a doubt, improved. There are more newspapers, there’s freer media, and a lot of the exiled media have moved back into Myanmar. So, there is more information available and that’s a good thing. We have to remember that there is a pace of opening up that all countries find on their own.

What has happened of course is that reporting restrictions from Rakhine state have gotten tougher, and that’s been a problem for people who want to know what’s happening [in that region]. Clearly there’s a big important story that concerns not just Myanmar, but the rest of the region and the rest of the world. We, like everybody else, would like to have much more open access to see what’s really happening.

Beyond the detention of Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, there have been far more arrests in recent years of journalists … that obviously brings a chilling effect on the press in Myanmar. That cannot be a good thing for freedom of information and for the citizens of Myanmar.

Have the arrests impacted Reuters’ ability to report and cover Myanmar and Rakhine state?

Has it impacted our ability? Well, two of our best reporters are in jail–so yes.

But, has it dampened our resolve to cover the country well? Has it chilled us in any way from the kind of coverage that Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo were doing? No. Not at all.

Do you think that by targeting Wa Lone, Kyaw Soe Oo, and Reuters, the Myanmar government is sending a warning to the media to end critical news coverage?

There’s been any number of arrests–again not only of Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo–in the last few years [and] I think journalists have clearly seen a message, “Be careful about your coverage.”

It’s never a good thing when any country arrests journalists for doing their job and I think that while some journalists will be deterred, others will just be more careful, and in some cases that will spur people on to want to do even more coverage.

Do you have hope that Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo will be able to walk free?

I have to be hopeful. If we weren’t hopeful we wouldn’t be doing everything that we’re doing. We think we have a strong case. You can see the way it’s gone, you can see the contradictory testimony of the prosecution, you can see the police captain’s testimony about how this was a set up. You have to look at all of those things with an impartial eye, and on the face of it, they should be freed today. We’re going to keep working on it until they get out.

What else should people know about your colleagues and this case?

When [Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo] hear about support locally and around the world, people that they’ve never met [who] are arguing and fighting for their freedom, they and their families are incredibly grateful. It gives them a real sense that they’re not in this by themselves.