Senegalese journalists say justice is not on their side when they are victims of abuse by powerful officials or security forces. I met recently in Dakar with journalists targeted with criminal acts in apparent reprisal for their work. In these two high-profile cases, CPJ has found evidence of political influence on the judiciary.

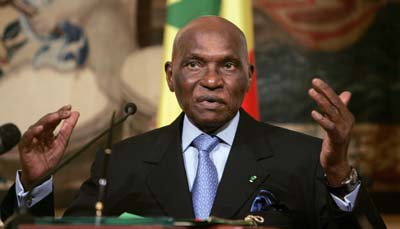

Three years ago this month, on June 21, 2008, reporters Boubacar Kambel Dieng of Radio Futurs Médias and Kara Thioune of West Africa Democracy Radio were the victims of scuffle with police officers following a soccer match at the capital Dakar’s Léopold Sédar Senghor Stadium. Dieng’s tape recorder captured the cries and shrieks of the two handcuffed journalists as officers punched and kicked them in a secluded room inside the stadium. The shocking audio was later broadcast on RFM. Yet even as mounting public outrage forced the government to announce an investigation and formal complaints by Dieng and Thioune were filed, top Senegalese officials appeared to interfere in the case and predetermine its outcome. Interior Minister Cheikh Tidiane Sy released a press statement blaming the journalists for the violence, accusing Dieng of “provoking” the policemen by “punching one of the officers.” President Abdoulaye Wade picked senior magistrate Mahawa Sémou Diouf to oversee preliminary investigations while repeating his interior minister’s accusation against the journalists during a press conference in Chicago.

Authorities then transferred the case to a military tribunal, arguing that it was more competent to adjudicate allegations of misbehavior by members of the security forces. It was not until November 26, 2010 that the journalists’ three indicted aggressors, warrant officer Lamidou Dione and peace officers Moussa Coulibaly and Mbaye Diouf, faced reckoning. But of the three officers, only Diouf was convicted on charges of “aggravated assault and battery, acts of torture,” and sentenced to a suspended one-month prison sentence and ordered to pay 750,000 CFA francs in damages to the journalists.

Months after the verdict, Thioune and Dieng are unsatisfied and cynical about the effectiveness and independence of Senegalese justice. “I’m not satisfied with the verdict and the trial was neither just nor fair, and it’s a shame for Senegalese justice,” said Dieng, who was hospitalized for three weeks for injuries sustained in the beating. He contested the competence of the military tribunal and claimed the court refused to hear witnesses who could have testified in his favor. “The trial is over, there’s no means to appeal and even if there was, I would not have done it.” Thioune went further: “I’m persuaded that the judges received instructions. Otherwise, for policemen who did what they did that day, with all the humiliation, the blows and injuries and violence we suffered, this trial is far from being just and fair.”

Perceived unfairness also marked the case of prominent journalist Abdou Latif Coulibaly, editor of La Gazette, a weekly critical of the government. On the night of October 5, 2010, assailants broke into Coulibaly’s home, taking his laptop, mobile phones and his 4×4 Kia vehicle. Police arrested five men, but only two were convicted and sentenced to prison terms. Officers returned the stolen items to Coulibaly, but the journalist told CPJ that he noticed sensitive files on his laptop, which were basis for future investigative stories, were missing. “The ‘burglars’ must have opened my computer and deleted some files. At this time, I’m wondering if this break-in was not masterminded,” he said.

True or not, this possible lead appeared not to have been explored by the Senegalese police during its investigation. In an interview with CPJ, national police spokesman Col. Aliou Ndiaye was quick to brush aside any lead other than a mundane criminal act. “The facts of the case demonstrate that it was just a break-in because neither of the defendants ever cited the name of a mastermind to police or judicial authorities,” he said. He went on to say that the case was closed and that “the work of the police was not to check the journalist’s computer but to find it and return it.”

Perhaps the break-in would not have raised suspicions if Coulibaly was not a top government critic who regularly takes on the ruling elite with dossiers breaking high-profile government corruption scandals. In fact, Coulibaly is facing multiple criminal defamation prosecutions brought by top officials, and is currently appealing two separate suspended prison sentences. Commenting on the outcome of the break-in at his residence, Coulibaly called Senegalese justice “corrupt and disorganized,” an assertion disputed by Senegalese High Commissioner for Human Rights Mame Bassine Niang. “Senegalese justice is professional and independent. As the first female lawyer in Senegal, I have no doubt about it,” she told CPJ. “President Wade has great respect for journalists and the government does not get itself involved in cases before justice,” she added.

Yet Wade, a career lawyer, has prominently used his power to intervene decisively in a case in which Farba Senghor, his former transport minister and the chief propagandist of his ruling PDS party, was found responsible for masterminding the August 17, 2008 ransacking of two critical newspapers, L’As and 24 Heures Chrono. Among the assailants arrested by police were a driver and bodyguards of Senghor, but state prosecutor Ousmane Diagne declared in an interview that only Wade could “authorize” criminal prosecution of a cabinet minister. Wade eventually sacked Senghor from the government, only to dictate the terms under which his subordinate would face justice. In a subsequent statement to reporters, the president said Senghor would be tried before the High Court of Justice, a tribunal run by the PDS-controlled parliament that handles cases involving public officials.

Nearly three years later Senghor, whom the president considers as close as a “son,” has yet to be tried by the High Court and is leading Wade’s political campaigns ahead of 2012 presidential elections. Meanwhile, the perpetrators of the attacks on L’As and 24 Heures Chrono are all free, pardoned by the president shortly after they were sentenced to prison terms.

Reporting from Dakar. Nassirou Diallo contributed to this report from New York.