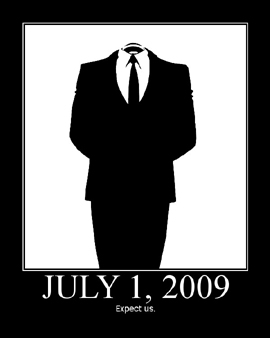

A self-styled army of Internet users, Anonymous Netizens, has announced its intention to wage war on government censors, starting July 1. Global Voices Online has the text in English; it’s also here in Chinese. Whether their scheduled attack (its nature is not specified) will be felt or not, the irritation of the document’s drafters is palpable: “NOBODY wants to topple your regime.”

The reason is this month’s massive censorship drive in China, ostensibly mounted to protect citizens from online obscenities. Substitute the phrase “antigovernment” for “vulgar” or “pornographic,” and it becomes clear why the new measures are a concern to journalists and internet users.

Google’s English language search engine has spread large amounts of vulgar content that is lewd and pornographic, seriously violating China’s laws and regulations,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Qin Gang told reporters after Google.com appeared inaccessible in parts of China last week, according to China Daily. The accusation lent credence to Internet users’ assumptions that the site and related services, including Gmail, had been officially censored. Google acknowledged only that it had experienced some interruption. “We are investigating the matter, and hope that (we) can restore all the services as soon as possible,” the company said in a statement on Thursday, according to Agence France-Presse.

But whether the apparent block was instigated to suppress porn or dissent, the logic behind it was hard to fathom. China’s Information Ministry already has sophisticated filters in place to limit banned content. What’s more, pages that could not be reached through Google’s English searches were still widely available on the Chinese version, Google.cn, or on Google’s main Chinese competitor, Baidu, according to analyst Rebecca MacKinnon.

Even if you overlook the fallacy that search engines actively “spread” content, rather than merely facilitating access to it, the action still makes no sense. Pornography (and information that challenges China’s government) can still be viewed; but a lot of irate people can’t check e-mail. Patience with official interference in Web use was already wearing thin, both domestically and internationally, following the furor over soon-to-be-mandated censorship “Green Dam” software. Now, for many, it has snapped altogether.

China’s electronic surveillance capabilities have long posed grave threats to citizens’ freedoms. Liu Xiaobo, the democracy activist and writer, was charged this month with attempting to subvert state power, according to international news reports. He was arrested in December 2008, the day before Charter ’08, a political manifesto he is accused of co-authoring, was circulated online. A Tibetan guide was recently sentenced to three years in prison for sending e-mails and text messages that “distorted the facts and true situation regarding social stability in the Tibetan area” following riots in the region in March 2008, according to the Dui Hua Foundation, a San Francisco-based advocacy group for political detainees in China.

Chinese dissidents oppose rights violations of this kind, but media control generally prevents a public outcry. Yet if the Anonymous Netizens (“innumerable … omnipresent … omnipotent … unstoppable”) are anything to go by, the latest censorship measures have tapped into a vein of opposition that is much more mainstream. When they tell the Internet censors of China, “YOU are waging this war on yourself,” it’s hard not to feel they have a point.