In Peru, a surprising reversal by the Supreme Court leaves a slain reporters family seeking justice.

| YUNGAY, Peru |

May 30, 2007

|

|

|

On the night of July 21, 2006, Dina Ramírez Ramírez—a kindergarten teacher in Yungay, a small town just north of Lima—received a startling telephone call from a friend in the capital: The Peruvian Supreme Court had just released the five people who had been convicted in her husband’s murder.

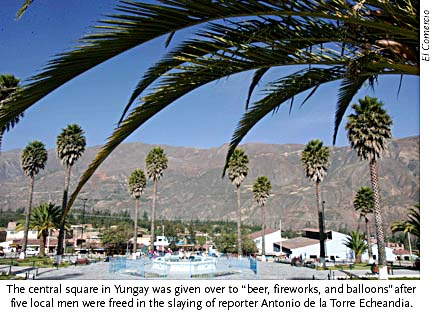

The Supreme Court’s written ruling—and the reasoning for its decision—would not be released for more than a month, but León and the others were freed immediately. The mayor retook office, and his supporters threw a party in Yungay’s central square “with beer, fireworks, and balloons,” Ramírez said. León, she said, publicly threatened her with jail if she pressed the case further. Menacing notes were slipped under her front door, and anonymous callers threatened to kill her, “like a dog, just as my husband.” When it was finally released, the court’s 18-page ruling essentially swept aside the prosecution’s case. The defendants’ statements were obtained through coercion, the remaining evidence was circumstantial, and the motive was insufficient because the journalist had criticized many politicians, the high court found.

As Ramírez continued to seek answers and press for a reopening of the case, threats against her family escalated. Fearing for their safety, she and her three children moved to Lima with help from the local press freedom group Instituto Prensa y Sociedad (IPYS) and emergency funds from CPJ. Ramírez and IPYS have now lodged a complaint with the Washington-based Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, alleging that the Peruvian government violated the rights of de la Torre and his family by allowing threats, harassment, and ultimately murder to go unpunished. León, who later lost a bid for re-election, did not return messages from CPJ seeking comment for this story. Lawyers for León and the other defendants also did not return messages seeking comment. Since 2004, CPJ has documented a rising incidence of threats and attacks against provincial reporters in Peru; two other radio journalists critical of local authorities have been murdered in the last three years. For many Peruvian journalists, then, the outcome of the de la Torre case has great significance. T Back at the radio station, he aired regular reports on alleged corruption in the local government. “We had proof for every accusation,” said his co-host, Rory Huaney Rodríguez. “We had documents that supported everything we said.” Nonetheless, in September 2003, León filed a criminal defamation suit against Huaney and de la Torre. By then, a pattern of threats and violence had emerged. CPJ interviews and a review of hundreds of pages of police records and court documents from the trial and the appeal depict an escalating series of attacks. For almost a year before the killing, León regularly called de la Torre’s house and confronted him in the street, threatening to kill him or send him to jail, Ramírez told CPJ. Anonymous threatening notes were pushed under the front door, and menacing calls were placed to the radio station. Peruvian National Police records show that by October 2003 the threats had turned violent: Unidentified individuals drove a car into de la Torre’s home; León’s wife allegedly beat the journalist with a cane; a homemade bomb exploded outside de la Torre’s house; a shack owned by the journalist was set on fire. De la Torre lodged official complaints after each attack, but there was little evidence that local police seriously investigated, Ramírez told CPJ.

On February 14, 2004—a Saturday—de la Torre left home shortly after noon intending to do some work at the radio station. Along the way, he met an acquaintance, local teacher Antonio Torre Camones, and the two spent much of the day together at a neighborhood bar, according to witnesses. Around 7:30 p.m., court documents say, the two went to another bar, where León, his daughter, her boyfriend, and three drivers from the mayor’s office had gathered for a small party. A videotape introduced by the prosecution shows an altercation between the journalist and one of the drivers, Hipólito Casiano Vega Jara. As de la Torre and Torre walked away from the bar at 8:30, court documents say, two men emerged from bushes about 200 feet away to attack the journalist. An autopsy found that two weapons were used in the stabbing. Torre ran away; prosecutors later alleged that he took part in the murder plot by luring de la Torre to the party. By 9 p.m., a hysterical neighbor was rapping on Ramírez’ door and crying: “Your husband was stabbed and he’s bleeding.” Ramírez and her eldest son, José, found de la Torre on the ground, nearly unconscious, covered in dirt and blood. Ramírez said her husband told José, “Casiano [Vega] is the one who did this” as they drove in a taxi to a local clinic. De la Torre died on a gurney moments after arriving at the clinic. Local police soon arrested Vega, the driver accused by the journalist, and Torre, the teacher. Suspect began to turn on suspect, and, though none would admit involvement in the slaying, their statements portrayed a politically motivated series of attacks leading up to the night of the murder. Vega told investigators that Antenor Alfonso Figueroa Mejía and Pedro Demetrio Ángeles Figueroa, fellow drivers from the mayor’s office, had information on the killing. According to court documents, Vega said the co-workers had earlier vandalized the journalist’s home and the radio station. Figueroa and Ángeles denied involvement in the slaying but confessed to the earlier harassment and accused León of masterminding those attacks. In his statement, Figueroa said the mayor had wanted to stop the journalist’s radio commentary. Ángeles also told authorities that Moisés David Julca Orillo, boyfriend of the mayor’s daughter, had spent February 14 with León and later vowed to kill de la Torre. Julca fled Yungay after the slaying and, though charged, was never apprehended. At the party, Vega said, he overheard the mayor saying, “Let [de la Torre] enjoy the end of his life.” León was arrested on March 17, 2004. National police conducted the initial investigation and a criminal judge oversaw the collection of evidence. During the probe, Léon, Torre, Vega, Figueroa, and Ángeles were sent to the same prison in Huaraz, capital of Áncash. Soon after their imprisonment, Ángeles and Figueroa recanted their statements, claiming police had coerced them. The Public Ministry ordered an immediate inquiry into coercion and torture allegations, which were brought forward by León as well. In medical documents reviewed by CPJ, the ministry found no physical evidence of brutality in León and Figueroa’s cases. In Ángeles’ case, investigators found a small scrape. The court concluded that there was no evidence of torture.

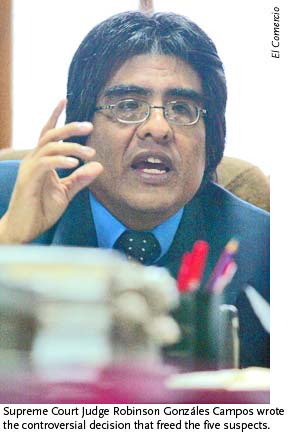

Ramírez recalled being “scared, really scared,” but also angry that the high court withheld its written ruling for several weeks. “I didn’t want to believe that his murder would go unpunished.” The decision, when it was finally made public, was widely criticized by the Peruvian press. Asked by the leading Peruvian daily El Comercio about the decision, Gonzáles said he would not comment. “Imagine the amount of time I would lose,” he said, “if I answered questions about every process that involves a journalist.” Gonzáles did not return messages from CPJ seeking comment. Press freedom advocates are concerned about the tone set by the high court and its potential effect on a similar case—the 2004 murder of Alberto Rivera Fernández, a host on Radio Frecuencia Oriental. Five men have been convicted of the crime. Pucallpa Mayor Luís Valdéz Villacorta, whom Rivera had linked to drug trafficking, is among three defendants still facing conspiracy charges. Ramírez and IPYS are asking the Inter-American Commission—the human rights monitoring arm of the Organization of American States—to review the de la Torre case and urge that it be reopened. The Peruvian constitution would allow the case to be retried if new evidence surfaced that refuted the Supreme Court’s ruling. If, for example, the alleged accomplice Julca were arrested, his testimony could pry open the case again.  They are also asking the commission to find that the Peruvian government failed to ensure justice, and to order unspecified damages. Restitution, Ramírez told CPJ, would allow her family to permanently relocate to Lima, where they would be safe from intimidation and threats. The commission’s decision could take up to a year. In the meantime, Ramírez has asked the commission to urge the Peruvian government to provide her with police protection. Regardless, Ramírez said, she will not keep silent. “I don’t want my husband’s death to disappear.” María Salazar is research associate for CPJ’s Americas program. |

||

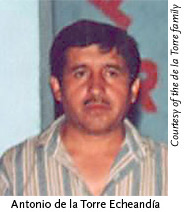

Her husband, radio journalist Antonio de la Torre Echeandía, had died after being stabbed 10 times on a street in Yungay, in the western province of Áncash, in February 2004. After a police investigation and trial that stretched out over nearly two years, a Superior Court panel convicted local Mayor Amaro León León and four others of plotting and carrying out the slaying. The three-judge panel based its decision on the testimony of witnesses, a dying utterance by the victim, and the self-incriminating statements of three of the accused, court records show. The judges deemed that the motive—silencing de la Torre, a constant critic of the mayor—was supported by a well-documented history of animosity between the two and a series of previous attacks against the journalist and his family. The defendants appealed to the Supreme Court, Peru’s highest judicial body.

Her husband, radio journalist Antonio de la Torre Echeandía, had died after being stabbed 10 times on a street in Yungay, in the western province of Áncash, in February 2004. After a police investigation and trial that stretched out over nearly two years, a Superior Court panel convicted local Mayor Amaro León León and four others of plotting and carrying out the slaying. The three-judge panel based its decision on the testimony of witnesses, a dying utterance by the victim, and the self-incriminating statements of three of the accused, court records show. The judges deemed that the motive—silencing de la Torre, a constant critic of the mayor—was supported by a well-documented history of animosity between the two and a series of previous attacks against the journalist and his family. The defendants appealed to the Supreme Court, Peru’s highest judicial body. De la Torre’s family and colleagues were stunned. The trial court had probed the coercion allegation but determined that the defendants’ lawyers were present when the statements were given and that no physical evidence supported the complaint. De la Torre had indeed criticized other politicians, but only León’s entourage was with the journalist on the night he died.

De la Torre’s family and colleagues were stunned. The trial court had probed the coercion allegation but determined that the defendants’ lawyers were present when the statements were given and that no physical evidence supported the complaint. De la Torre had indeed criticized other politicians, but only León’s entourage was with the journalist on the night he died. he journalist and the mayor had met 10 years prior to the murder and, according to Ramírez, were close friends for some time. León and his wife were godparents to de la Torre’s youngest daughter; de la Torre had volunteered in two of León’s mayoral campaigns. But a rift arose after the journalist went to work as León’s spokesman in January 2003. Within months, he was dissatisfied with León’s management, confronted the mayor, and was demoted to guard. Days later, de la Torre returned to his job at Radio Órbita.

he journalist and the mayor had met 10 years prior to the murder and, according to Ramírez, were close friends for some time. León and his wife were godparents to de la Torre’s youngest daughter; de la Torre had volunteered in two of León’s mayoral campaigns. But a rift arose after the journalist went to work as León’s spokesman in January 2003. Within months, he was dissatisfied with León’s management, confronted the mayor, and was demoted to guard. Days later, de la Torre returned to his job at Radio Órbita.  “He was too brave,” Ramírez said of her husband. “Even though everyone asked him to stop [his commentary], he said that he had to keep going.”

“He was too brave,” Ramírez said of her husband. “Even though everyone asked him to stop [his commentary], he said that he had to keep going.” Following their convictions, the mayor, his three drivers, and the teacher were each sentenced to 17 to 20 years in prison. By summer 2006, the Supreme Court had docketed their appeal. In accordance with the Peruvian legal system, the case was randomly handed to a judge—one of five on the high court assigned to criminal cases—who was charged with reviewing the file and presenting his findings to the others. In this case, Judge Robinson Gonzáles Campos was placed in charge of the case. Following a private vote, the court ordered the release of the five defendants and reserved the right to issue a ruling in the case against Julca, who had fled.

Following their convictions, the mayor, his three drivers, and the teacher were each sentenced to 17 to 20 years in prison. By summer 2006, the Supreme Court had docketed their appeal. In accordance with the Peruvian legal system, the case was randomly handed to a judge—one of five on the high court assigned to criminal cases—who was charged with reviewing the file and presenting his findings to the others. In this case, Judge Robinson Gonzáles Campos was placed in charge of the case. Following a private vote, the court ordered the release of the five defendants and reserved the right to issue a ruling in the case against Julca, who had fled.