CPJ Investigates the Attack on the Palestine Hotel

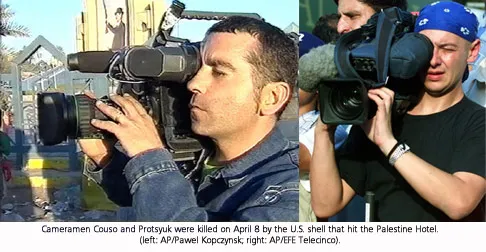

New York, May 27, 2003— Just before noon on April 8, 2003, journalists covering the battle of Baghdad from the balconies of the Palestine Hotel looked on as the turret of a U.S. M1A1 Abrams tank positioned about three quarters of a mile away on the Al-Jumhuriya Bridge turned toward them and unleashed a single round. The shell struck a 15th-floor balcony of the hotel, fatally wounding veteran Reuters cameraman Taras Protsyuk and Spanish cameraman José Couso of Telecinco. Three other journalists were wounded in the attack.

About 100 international journalists were staying in the Palestine Hotel at the time of the strike. They had survived the dangers of war–including the “shock and awe” air campaign and the Iraqi security officials who had periodically searched their rooms and expelled and detained several of their colleagues–only to be fired on by a U.S. tank during one of the last days of combat.

About 100 international journalists were staying in the Palestine Hotel at the time of the strike. They had survived the dangers of war–including the “shock and awe” air campaign and the Iraqi security officials who had periodically searched their rooms and expelled and detained several of their colleagues–only to be fired on by a U.S. tank during one of the last days of combat.

A Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) investigation into the incident–based on interviews with about a dozen reporters who were at the scene, including two embedded journalists who monitored the military radio traffic before and after the shelling occurred–suggests that attack on the journalists, while not deliberate, was avoidable. CPJ has learned that Pentagon officials, as well as commanders on the ground in Baghdad, knew that the Palestine Hotel was full of international journalists and were intent on not hitting it.

However, these senior officers apparently failed to convey their concern to the tank commander who fired on the hotel.

However, these senior officers apparently failed to convey their concern to the tank commander who fired on the hotel.

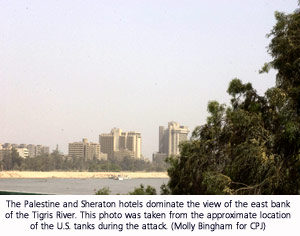

Photos commissioned by CPJ and taken at the bridge from where the tank fired show that the 17-story high Palestine Hotel was distinct against the Baghdad skyline. Along with the nearby Sheraton Hotel, it towered over all other buildings in the area.

Based on the information contained in this report, CPJ calls afresh on the Pentagon to conduct a thorough and public investigation into the shelling of the Palestine Hotel. Such a public accounting is necessary, not only to determine the causes of this incident, but also to ensure that similar episodes do not occur in the future.

Radio traffic

Chris Tomlinson, an Associated Press (AP) reporter embedded with an infantry company assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division’s 4th Battalion 64th Armor Regiment, arrived in central Baghdad on April 7 after a two-and-a-half week journey from Kuwait. Beginning at dawn that day, the battalion engaged Iraqi forces in skirmishes that continued for the next 36 hours. On April 8, as the battalion continued to push into the heart of Baghdad, U.S. soldiers encountered stiff resistance from Iraqi forces. Tomlinson spent the day inside an impromptu U.S. command center established in Saddam Hussein’s presidential palace on the west side of the Tigris River. By toggling a switch on a military radio, Tomlinson could listen to communication within the company unit, and also to the battalion tactical operations frequency, which allowed him to hear conversation between the tank company commander, Capt. Philip Wolford, and his superiors.

At around dawn on April 8, intense fighting resumed on the west side of the Tigris in the vicinity of the Al-Jumhuriya Bridge. Reporters, who had clustered on the balconies of the Palestine Hotel, located on the eastern bank of the Tigris, observed a significant counterattack by Iraqi forces armed with light arms, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), and mortars. The attack continued for several hours, and, according to AP reporter Tomlinson, snipers on tall buildings aimed at the hatches of the tanks, eventually wounding two members of Wolford’s battalion.

At around dawn on April 8, intense fighting resumed on the west side of the Tigris in the vicinity of the Al-Jumhuriya Bridge. Reporters, who had clustered on the balconies of the Palestine Hotel, located on the eastern bank of the Tigris, observed a significant counterattack by Iraqi forces armed with light arms, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), and mortars. The attack continued for several hours, and, according to AP reporter Tomlinson, snipers on tall buildings aimed at the hatches of the tanks, eventually wounding two members of Wolford’s battalion.

Fighting grew so intense that senior U.S. military officers called in air strikes on an intersection and various buildings on the west bank to weaken the Iraqi positions. According to press reports, dozens of Iraqis were killed. By late morning, U.S. forces began focusing their attention on the other side of the Al-Jumhuriya Bridge. (Earlier that morning, near where the fighting had occurred on the west side of the bridge, a U.S. air-to-surface missile struck the Baghdad office of Qatar’s Al-Jazeera news channel, killing reporter Tareq Ayyoub and wounding his cameraman, an incident that CPJ continues to investigate.)

Throughout the morning, Tomlinson heard radio communications between company units and between officers on the battlefield and their commanders. At some point, U.S. forces recovered an Iraqi radio and began monitoring communications between Iraqi forces. An Arabic-speaking U.S. intelligence officer was able to determine that an Iraqi forward observer, or spotter, was directing Iraqi fighters who were skirmishing with U.S. troops. The tanks, meanwhile, had received RPG, sniper, and mortar fire, according to Tomlinson.

At about mid-morning, two M1A1 Abrams tanks from the Alpha Division moved onto the Al-Jumhuriya Bridge, which spans the Tigris River. A videotape shot by a French television crew on the 14th floor of the Palestine Hotel shows the tanks firing several rounds into a building on the east side of the river with satellite dishes on the roof. The turret of one tank was raised, then lowered. A third tank strayed out a short distance on the bridge. According to Tomlinson, who was continuing to monitor radio communication, the tanks were frantically searching for the spotter.

Another U.S. reporter, Jules Crittenden of the Boston Herald, who was embedded with the Alpha Company of the 4th Battalion 64th Armor Regiment, confirmed Tomlinson’s account. Crittenden arrived near the battle scene in an armored personnel carrier. “There was a tremendous degree of concern because everybody was looking trying to figure out where this observer was–in fact, we were doing it, too,” Crittenden said. “We were all concerned that we were about to get an artillery barrage, which we didn’t want to happen for obvious reasons.”

Tomlinson, who has himself served seven years in the army, noted that, “The first thing they teach you when you’re a tanker or an infantry man is to kill the forward observer…that’s the highest priority target.” He continued, “If you can kill the forward observer, you have no one to direct the ground forces [or artillery fire]. And therefore you completely take away their value.”

At some point before the shelling of the hotel, while the tanks were on the bridge looking for the observer, brigade commander Col. David Perkins approached Tomlinson and reporter Greg Kelly from FOX News. (CPJ contacted Greg Kelly but FOX officials said he was not available for comment. However, a FOX official confirmed to CPJ that Perkins had approached Kelly.)

In some desperation, Perkins explained that U.S. forces were under fire from Iraqis in buildings on the east side of the Tigris, and that they were considering calling in an air strike. Perkins was aware that the Palestine Hotel was on the east side of the river in the general vicinity of where the fire was coming from. He was also aware that the hotel was full of Western journalists. Tomlinson said he believed that all the commanders, including Lt. Col. Philip DeCamp and even Captain Wolford, would have known that information since the 2nd Brigade had captured the Al-Rashid Hotel the previous day, and most people knew that the journalists there had moved to the Palestine Hotel. Perkins had a general location–probably within a few hundred meters, according to Tomlinson–and he wanted Tomlinson’s help in physically identifying the building so that it would not be hit. (He also noted that the satellite maps used by the military were about 10 years old.)

Tomlinson frantically called The AP office in Doha, Qatar, in an effort to get a description of the hotel and to reach people staying at the Palestine. His plan was to relay a message to the journalists inside and ask them to hang bed sheets out the window to make the building more easily identifiable to U.S. forces.

At about the time that Tomlinson was trying to locate the Palestine Hotel, in the late morning, one of the tank officers on the Al-Jumhuriya Bridge who was looking for the spotter radioed that he had located a person with binoculars in a building on the east side of the river. Exactly how much time lapsed between the tank officer identifying this target and the actual firing of the tank shell is not clear from Tomlinson’s monitoring of the radio traffic.

At about the time that Tomlinson was trying to locate the Palestine Hotel, in the late morning, one of the tank officers on the Al-Jumhuriya Bridge who was looking for the spotter radioed that he had located a person with binoculars in a building on the east side of the river. Exactly how much time lapsed between the tank officer identifying this target and the actual firing of the tank shell is not clear from Tomlinson’s monitoring of the radio traffic.

In an interview with the French weekly Le Nouvel Observateur, Captain Wolford hinted that he gave an immediate order to fire. However, in an interview with Belgium’s RTBF television news that aired in May, Shawn Gibson, the tank’s sergeant, said that after he spotted someone talking and pointing with binoculars, he reported it to his commanders but did not receive an order to fire for about 10 minutes. Jules Crittenden, who was located on the west side of the river with U.S. forces at that point, also recalls troops at the very least discussing the target. “I was aware that they had spotted someone with binoculars and they were getting ready to fire,” Crittenden said. “This was being discussed on the radio.”

According to Tomlinson, the round that was fired was a heat round, an incendiary shell that is intended to kill people and not destroy buildings. If the tank had fired an armor-piercing round, the damage to the building would have been much more severe.

The immediate reaction from U.S. commanders to the attack on the Palestine Hotel was anger and consternation. Lt. Col. Philip DeCamp, Captain Wolford’s commanding officer, began screaming over the radio, “Who just shot the Palestinian [sic] Hotel?” according to Tomlinson. Tomlinson listened as DeCamp confronted Wolford. “‘Did you just f***ing shoot the Palestinian [sic] Hotel?'” he demanded of Wolford.

Tomlinson said that at first, Wolford was not sure that what he had hit was in fact the hotel. Tomlinson continues:

Tomlinson said that at first, Wolford was not sure that what he had hit was in fact the hotel. Tomlinson continues:

“[After a delay of some minutes] Wolford says, ‘Yes, yes. We had an observer up there. And DeCamp says, ‘You’re not supposed to fire on the hotel.’ And then there is a brief discussion about what he did see and why did he fire because this was very serious. They weren’t supposed to shoot at the Palestine Hotel.”

Afterward, DeCamp ordered Wolford to cease firing and drove his tank to meet Wolford, apparently to have a private discussion.

After hearing the exchange, Tomlinson immediately went to Colonel Perkins, DeCamp’s commanding officer, to tell him that his effort to locate the Palestine Hotel to prevent it from being hit by an air strike was too late.

“I know, I know,” Perkins told Tomlinson. “I have just given the order that under no circumstances is anyone to shoot at the Palestine Hotel, even if they are taking fire, even if there is an artillery piece on top of the roof. No one is allowed to shoot at the Palestine Hotel again.”

The reaction

The U.S. attack on the Palestine Hotel quickly became a huge story. It happened during some of the most intense fighting between U.S. and Iraqi forces in Baghdad, and dozens of journalists were eyewitnesses or had been in the hotel at the time. The journalists inside were shocked and angered by the death of two of their colleagues. They were also at a loss to explain how a U.S. tank could have fired at the hotel, whose location was widely known to the Pentagon. News organizations were in contact with the Defense Department about their reporters’ locations, and the hotel was referenced daily in international media reports.

Journalists in the hotel were also at a loss to explain how the tank officer could have failed to notice a 17-story building–one of the tallest in Baghdad–that had journalists on its balconies and even on its roof. In fact, many had been out on their balconies during the previous 24 hours covering the fighting on the west side of the river. The Palestine Hotel, along with the Sheraton Hotel next door, dominates the landscape; one journalist said the two buildings were as easily identifiable as New York’s twin towers.

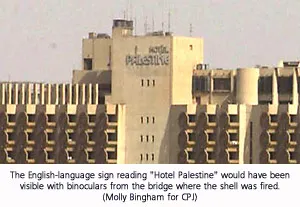

In fact, photographs commissioned by CPJ and taken from the approximate point on the Al-Jumhuriya Bridge from where the tank shell was fired show that the Palestine Hotel and the nearby Sheraton tower over the surrounding buildings. An enormous sign reading “Hotel Palestine” in English is also discernible in the photographs. While it is not clear whether the sign would have been readable to the naked eye, it certainly would have been easy to read with binoculars.

Because journalists had a clear view of the tanks on the Al-Jumhuriya Bridge, they assumed that the tank commanders could see them–though in fact, the tanks were approximately three quarters of a mile from the hotel. Journalists also said they were surprised because there was a lull in the battle at the time the tank fired, and, in any case, the Palestine Hotel was removed from the action. In fact, at least some–possibly several–journalists who had been observing the battle from their balconies went inside their rooms to file stories, thinking the action was finished.

“I was taking pictures the whole morning,” said Patrick Baz, an AFP photographer who covered the battle from his balcony of the Palestine Hotel. “There were helicopters. A whole Hollywood war. We were watching everything, and they could see us. From the first day they moved into the palace [the day before] until they shot…they could see us the same way we could see them.”

Caroline Sinz, a reporter for France 3 television whose crew filmed the tanks on the bridge before they opened fire on the hotel, says the bombardments and fighting stopped at around 11:20 a.m.

“The fighting was intense from 6 a.m. until 11:20, then it was very quiet,” explained Sinz. “We were still filming. I told my cameraman that he should still film because we need to be careful. …We filmed exactly 15 minutes before the shooting, and you can hear nothing.”

Other journalists are less definitive that it had become completely quiet, noting that there had been intense fighting all morning. Jerome Delay, an AP photographer who was in the Palestine Hotel, noted that it was difficult to tell whether the tanks did or did not receive fire from the eastern bank of the river because of the hotel’s distance from the bridge. Jules Crittenden, the embedded U.S. reporter who was on the western side of the bridge, reported hearing on the radio that there were up to 40 Iraqi RPG teams on the eastern side. According to journalists in the hotel, the tanks took fire from various government buildings on the eastern bank in the period before the shelling of the hotel. In fact, Sinz’s tape shows the tanks firing on several targets on the east side of the bridge. It also shows a dark plume of smoke rising from the west side of the river–described by one reporter as an air strike–for several minutes before the tank raises its turret and fires a single round at the hotel. Explosions of what appear to be tank fire also occasionally echo in the background.

Most journalists did not immediately realize that their hotel had been hit. “I did not react. I did not believe it was in the hotel,” Patrick Baz explained. “I saw in the parking lot people pointing at the building. I didn’t realize what was going on. I saw people running. I thought it hit the building behind.” When Baz realized that some journalists on his floor had been injured, he ran for the first aid kit.

“There were people screaming, yelling, crying, panicked. I saw this guy who was lying on the bed and injured,” Baz recounts. “I remember his face was covered with blood. There was a hole in his leg. There was a big hole, but it wasn’t bleeding.”

The shell hit a 15th-floor corner balcony of the suite used by Reuters news agency, mortally wounding Taras Protsyuk, Reuters’ Ukrainian-born cameraman who had been on the balcony, his camera set up though he was not filming at the time.

“Taras was lying on the floor on his back, unconscious,” Delay told the Los Angeles Times. “His jaws were locked. We forced open his jaws to get some air into him and got him breathing again.” Protsyuk was taken to a Baghdad hospital, where he died on arrival of abdominal wounds.

Paul Pasquale, a Reuters satellite dish technician who was on the balcony with Protsyuk, was injured, as were two other Reuters journalists on a separate 15th-floor balcony–Gulf bureau chief Samia Nakhoul and photographer Faleh Kheiber. Debris damaged the floor below, where Spanish cameraman José Couso had been filming. Like Protsyuk, Couso was taken to a Baghdad hospital, suffering from wounds to his leg and jaw. He died after surgery.

Journalists who were in Baghdad at the time offered several possible explanations for the shelling of the hotel: Some saw it as an unfortunate accident by a tank commander, but others called it a flagrantly reckless act by the U.S. military or even a deliberate attempt to intimidate journalists.

International press freedom groups, including CPJ, swiftly protested the incident. In an April 8 letter sent to U.S. secretary of state Donald H. Rumsfeld, CPJ noted that “[w]hile sources in Baghdad have expressed deep skepticism about reports that U.S. forces were fired upon from the Palestine Hotel, even if that were the case, the evidence suggests that the response of U.S. forces was disproportionate and therefore violated international humanitarian law [the Geneva Conventions].” The letter called on the Pentagon “to launch an immediate and thorough investigation into these incidents and to make the findings public.”

Centcom weighs in

A few hours after the incident, reporters at Central Command Headquarters in Doha, Qatar, questioned Brig. Gen. Vincent Brooks about the attack. He expressed regret for the loss of life but noted that being in areas where combat is occurring is dangerous, and that the military cannot know where journalists not “embedded” with U.S. forces are located on the battlefield.

He alleged that “combat actions” had occurred at the Palestine Hotel, and that “initial reports indicate that the coalition forces operating near the hotel took fire from the lobby of the hotel and returned fire.” When asked by a reporter why the tank would fire at the hotel’s upper level if fire was coming from the lobby, Brooks backtracked, stating that he “may have misspoken on exactly where the fire came from.” Later that day, Centcom issued a statement maintaining that commanders at the scene had reported that their forces came under “significant enemy fire from the Palestine Hotel in Baghdad.” Then Centcom, like Brooks had done earlier, blamed Iraqi forces for conducting military operations from civilian locations.

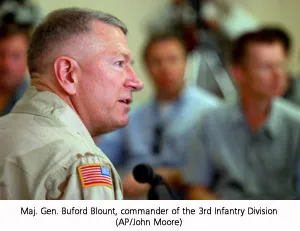

The statements from Centcom that day matched those of senior officers from the 3rd Infantry Division. Maj. Gen. Buford Blount, the division’s commander, told Reuters that the tank that had opened fire “was receiving small arms fire and RPG fire from the hotel and engaged the target with one tank round.” Colonel Perkins, the brigade commander who spoke with Tomlinson after the strike, also told Tomlinson that his unit took RPG fire from close in front of the hotel.

The statements from Centcom that day matched those of senior officers from the 3rd Infantry Division. Maj. Gen. Buford Blount, the division’s commander, told Reuters that the tank that had opened fire “was receiving small arms fire and RPG fire from the hotel and engaged the target with one tank round.” Colonel Perkins, the brigade commander who spoke with Tomlinson after the strike, also told Tomlinson that his unit took RPG fire from close in front of the hotel.

Many journalists who were eyewitnesses to the incident, or who had been in the hotel at the time, flatly deny the claim from Centcom and some commanders in Baghdad that the tank was returning fire emanating from the Palestine Hotel. Those who had been monitoring events from their balconies, which offered a full view of the surrounding area, attest that no gunfire or RPG fire had come from the hotel or its immediate vicinity.

“I think that’s quite impossible because on each floor and each room…even on the roof, there were journalists and photographers, and they were looking at what was going on,” recalled AFP reporter Sammy Ketz, who was on a 15th-floor balcony at the time of the incident. Anne Garrels, an NPR correspondent and CPJ board member who had reported from the Palestine Hotel throughout most of the conflict, echoed this point. “All of us were on our balconies watching the battle,” said Garrels, who had been on her balcony throughout the day but was at her desk in the hotel at the moment the shell hit. “We would have seen snipers in the building. You can imagine how rattled everyone is.” Colleagues who had been on the roof earlier, she said, also reported no signs of sniper activity or gunfire. Other journalists said that they already knew Iraqi forces might possibly use the hotel as cover, but that they never encountered armed Iraqi forces operating from the building during their time in Baghdad. Other journalists discounted the allegation of some U.S. officers that there was an Iraqi bunker near the hotel.

On April 10, Lt. Col. Philip DeCamp, the commander of the 4th Battalion 64th Armor Regiment, apologized for the incident in an interview with the Los Angeles Times and referred to himself as “the guy who killed the journalists.” But he also continued to assert that Iraqi fighters in bunkers at the base of the hotel had opened fire with AK-47s and RPGs at his tank unit. An earlier article in the Los Angeles Times quoted Captain Wolford, the company commander of the tank unit that opened fire on the Palestine Hotel, claiming that he had given the order to fire on the hotel after one of his tank gunners noticed someone from the hotel observing his unit with binoculars. Wolford told the newspaper he had received intelligence that men with RPGs were at the foot of the hotel. The Los Angeles Times, citing military sources, said that at the time, Wolford’s unit was coming under mortar fire from the hotel’s side of the river.

A few days later, Wolford told Jean Paul Mari of the French weekly Le Nouvel Observateur that his unit had been engaged in a “brawl” for several hours on the morning of April 8 and had received heavy enemy fire as they approached the eastern side of the Al-Jumhuriya Bridge. Two of his men were wounded that day, he said, and his tanks came under rocket fire from several directions, including the area around the Palestine Hotel. He told the magazine that after his men sighted an individual carrying binoculars, identified by someone in the unit as an artillery spotter, they opened fire. “Me, I return fire,” Wolford was quoted as saying. “Without hesitation, that’s the rule. I learned 20 minutes later that we had hit a hotel full of journalists.”

In the interview, Wolford maintained that he had no information from command headquarters that there were journalists in the building. “I don’t imagine for an instant that a piece of information sent by the headquarters of the division would not get to me,” he said. He told the Boston Herald‘s Crittenden that the hotel had not been marked on his maps. The tank officer, Sgt. Shawn Gibson, would later be quoted as saying that he, too, was unaware that the building was packed with journalists.

In response to CPJ’s letter to Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld, Pentagon spokeswoman Victoria Clarke wrote to CPJ acting director Joel Simon on April 14 stating that “coalition forces were fired upon and acted in self-defense by returning fire.” She acknowledged the Pentagon’s responsibility to exert caution on the battlefield but noted that news organizations had been warned that Baghdad would be a “particularly dangerous” place and should pull their reporters from the city.

A CPJ request to the Defense Department to interview Captain Wolford is still pending. CPJ is also awaiting the results of Freedom of Information Act requests for information about the incident.

Lingering questions

The last official communication from the U.S. government regarding the Palestine Hotel incident came in an April 21 letter from Secretary of State Colin Powell to Spanish foreign minister Ana Palacio. Powell wrote that a military review of the incident indicated that the U.S. tank had fired in response to “hostile fire appearing to come from a location later identified as the Palestine Hotel.” He concluded that “the use of force was justified and the amount of force was proportionate to the threat against United States forces.” The following week, during a visit to Spain, where the local media seethed at Spanish journalist Couso’s death, Powell reiterated that U.S. troops were not at fault and said the U.S. government would continue to investigate the incident.

There is simply no evidence to support the official U.S. position that U.S. forces were returning hostile fire from the Palestine Hotel. It conflicts with the eyewitness testimony of numerous journalists in the hotel.

While all indications are that the tank round was directed at what was believed to be an Iraqi spotter, other questions emerge. For example, how is it possible for a tank officer to observe a person or persons with binoculars, wait 10 minutes for authorization to fire, according to the tank sergeant, and, during that interval, not notice journalists with cameras and tripods located on other balconies, or the large, English-language sign reading “Hotel Palestine”? Moreover, the France 3 video shows that the tank had pointed its turret at the hotel earlier in the morning before the shelling occurred–possibly indicating that U.S. forces had the opportunity to obtain a good view of members of the media on balconies–but turned away.

According to Tomlinson, the effort by the tank officer to pass on the location of the alleged spotter occurred at a time when the brigade commander, Colonel Perkins, was frantically trying to locate the Palestine Hotel in order to avoid hitting it in an air strike. Why was the tank commander not instructed to recheck his target and make sure it was not the Palestine Hotel? And even before that, why were military units not made aware of a major civilian location on the battlefield?

According to Tomlinson, the effort by the tank officer to pass on the location of the alleged spotter occurred at a time when the brigade commander, Colonel Perkins, was frantically trying to locate the Palestine Hotel in order to avoid hitting it in an air strike. Why was the tank commander not instructed to recheck his target and make sure it was not the Palestine Hotel? And even before that, why were military units not made aware of a major civilian location on the battlefield?

The radio traffic monitored by Tomlinson, as well as Colonel Perkins’ reaction to the shelling of the hotel, raises questions about whether all appropriate measures were taken to avoid firing on the hotel. Clearly, Colonel Perkins was concerned that the hotel might be hit, and Lieutenant Colonel DeCamp was angry and upset once it actually was hit. Perkins told Tomlinson that he gave an order after the fact that the hotel should not be hit under any circumstances. If that was his goal, and his discussion with Tomlinson makes clear he was making extraordinary efforts to avoid hitting the hotel in an air strike, why had he failed to disseminate an order throughout the ranks that the hotel was to be avoided?

Lieutenant Colonel DeCamp appeared to be so upset with the strike that he ordered Wolford to cease fire and drove out to the area so he could have a private meeting with Wolford. What did they talk about when they met? Only an honest and thorough Pentagon investigation can make this clear.

Finally, remarks by Wolford seem to contradict his own statements and those of other officers. Wolford said in press interviews that he fired immediately, though the tank officer said there was roughly a 10-minute delay between the moment when he reported the spotter and when he received his order to fire. Wolford’s statements are also confusing since he said on the one hand that the tank that fired on the Palestine Hotel was “returning” fire but clearly stated at other times that the tank was firing at a spotter with binoculars. Which versions of these events are correct?

These and other questions can only be answered by the Pentagon, which should provide a full, public accounting of the events as they took place on April 8. Although U.S. secretary of state Colin Powell remarked in April that the incident was still under investigation, there have been few indications that a full, thorough, and public inquiry is forthcoming.

Joel Campagna is CPJ’s senior program coordinator responsible for the Middle East and North Africa. Rhonda Rhoumani a research consultant to CPJ’s Middle East and North Africa program.