After the murder of a radio journalist, Haiti’s press pulls back in fear.

Port-au-Prince — One often sees a dead journalist’s face on T-shirts worn by members of the Haitian press. The shirts commemorate Jean Léopold Dominique, a local radio station owner and political commentator gunned down last April along with his security guard, Jean-Claude Louissaint. They also send a message: in Haiti, anonymous threats to journalists cannot be dismissed as mere harassment.

Dominique, 69, was Haiti’s most prominent political journalist and a veteran advocate of free speech. He was also a close friend and political advisor to President René Préval. But while Dominique almost certainly died because of his journalism, it is not yet clear who killed him, or why.

Shortly after six a.m. on April 3, Dominique arrived at Radio Haitï Inter to host the seven a.m. news program. After Louissaint opened the gate to the station’s compound, located along the road from Port-au-Prince to the suburb of Pétionville, Dominique drove his car inside and parked. As he was about to enter the station, a single gunman entered the compound on foot and shot him seven times.

The gunman then fired two shots at Louissaint before fleeing in a Jeep Cherokee whose driver had been waiting for him outside the compound. Minutes after the attack, Dominique’s wife, Michele Montas, arrived at the station in a separate car and found her husband and Louissaint lying wounded on the ground. Police reached the scene soon afterward and rushed both victims to the Haitian Community Hospital in Pétionville, where they died of their wounds.

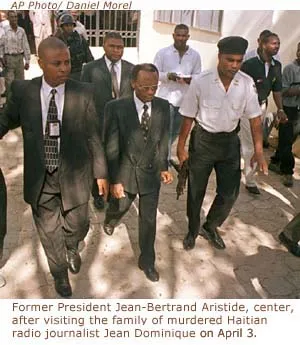

Sadly, Dominique’s murder was not an isolated case. Haitian journalists have always known to watch what they say. If they don’t, credible death threats murmured over the phone, leaflets slipped under radio station doors, and anonymous e-mails will help them remember. Local journalists see little hope for improvement if Jean-Bertrand Aristide resumes the presidency. Since leaving office in 1995, Aristide has continued to wield enormous influence; due to an opposition boycott, he is running virtually unopposed in presidential elections scheduled for November 26 (although they may be delayed until December). With the major opposition parties marginalized through violence and intimidation, many fear Aristide will rule by decree.

Sadly, Dominique’s murder was not an isolated case. Haitian journalists have always known to watch what they say. If they don’t, credible death threats murmured over the phone, leaflets slipped under radio station doors, and anonymous e-mails will help them remember. Local journalists see little hope for improvement if Jean-Bertrand Aristide resumes the presidency. Since leaving office in 1995, Aristide has continued to wield enormous influence; due to an opposition boycott, he is running virtually unopposed in presidential elections scheduled for November 26 (although they may be delayed until December). With the major opposition parties marginalized through violence and intimidation, many fear Aristide will rule by decree.

In the past, presidential decrees have not tended to favor independent journalism. After his election in 1995, President René Préval abolished the Ministry of Information, thereby eliminating any institutional contact between the press and government. “Since then, there have been no guarantees for freedom of the press,” said Ady Jean-Gardy, a journalist for the Haitian News Agency and general secretary for the Committee of the Press for Civic Action. “Any journalist who would dare say something against the government is likely to be arrested, or something else will happen to him.”

This pervasive intimidation affects sources as well as reporters. Many local economists and political observers will not even provide background on the political situation. Those who are willing to talk to the press often request a face-to-face interview, both because the phones could be tapped and to ensure that they are being interviewed by a legitimate reporter. And, because most Haitian media serve as mouthpieces for either the government or the opposition, local journalism often reads like mudslinging across an ideological divide.

This pervasive intimidation affects sources as well as reporters. Many local economists and political observers will not even provide background on the political situation. Those who are willing to talk to the press often request a face-to-face interview, both because the phones could be tapped and to ensure that they are being interviewed by a legitimate reporter. And, because most Haitian media serve as mouthpieces for either the government or the opposition, local journalism often reads like mudslinging across an ideological divide.

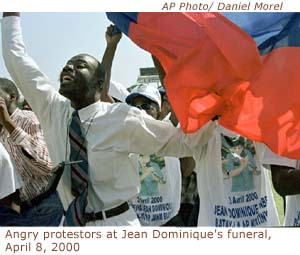

Last January, President Préval stepped back from a promise to sign the Declaration of Chapultepec, a regional press freedom pact that has been signed by nearly every head of state in the Americas. And on April 8, the day of Dominique’s state funeral (an honor accorded only to the most prominent Haitians), Radio Vision 2000, known for its anti-government stance, was visited by a mob of government-sponsored thugs who hurled stones and threatened to burn the building down.

The press must also contend with the muscle behind Haiti’s rapidly growing trade in illegal drugs. In recent years, the country has become a major staging post for cocaine and heroin on its way from Colombia to the United States. Because the drug economy remains a dangerous assignment, journalists usually limit their reporting to straightforward summaries of drug seizures. “If you talk about drugs, your body will be found in the corner,” said Guy Jean, owner and director of Radio Tropic FM.

Dominique was one of the few local journalists willing to explore this taboo topic. After his murder, a local judge questioned Dany Toussaint, a senator from the ruling Lavalas Family political party and an alleged drug lord whom Dominique’s station had criticized sharply in a program aired last October. As a legislator, Toussaint is immune from criminal prosecution. He has denied any involvement in the drug trade and has promised to help bring those responsible for Dominique’s murder to justice. But, on November 10, Toussaint ignored a judicial summons.

Dominique was one of the few local journalists willing to explore this taboo topic. After his murder, a local judge questioned Dany Toussaint, a senator from the ruling Lavalas Family political party and an alleged drug lord whom Dominique’s station had criticized sharply in a program aired last October. As a legislator, Toussaint is immune from criminal prosecution. He has denied any involvement in the drug trade and has promised to help bring those responsible for Dominique’s murder to justice. But, on November 10, Toussaint ignored a judicial summons.

Despite the use of caller ID and other security measures, Radio Haiti Inter continues to receive as many as three or four anonymous threats a week, according to Dominique’s widow, Michele Montas, who once co-hosted radio programs with her husband and is still the director of the station. Until the military relinquished power in 1994, it was generally presumed to be behind threats to journalists. No longer. “You don’t know where the threats are coming from,” Montas said.

Despite the use of caller ID and other security measures, Radio Haiti Inter continues to receive as many as three or four anonymous threats a week, according to Dominique’s widow, Michele Montas, who once co-hosted radio programs with her husband and is still the director of the station. Until the military relinquished power in 1994, it was generally presumed to be behind threats to journalists. No longer. “You don’t know where the threats are coming from,” Montas said.

Trenton Daniel, a former CPJ staff member, covers Haiti for Reuters and The Haitian Times.