Mahathir wins election, stifles media

Also in this report: A. Lin Neumann discusses the Malaysian press on the eve of elections in a news analysis.

In an exclusive essay for CPJ, Far Eastern Economic Review correspondent Murray Hiebert recounts his ordeal at the hands of the Malaysian legal system.

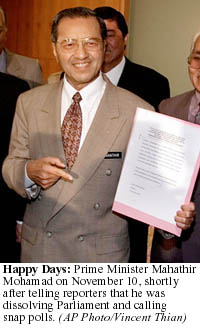

| Bangkok, November 30, 1999— Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s ruling coalition was returned to power in Malaysia’s November 29 general election, but the result will do little to staunch criticism that his government uses its power to stifle dissent and muzzle mainstream media. The National Front, which has governed Malaysia since independence in 1957, retained its overpowering two-thirds majority in parliament despite losing some ground to the Islamic party PAS (Parti Islam SeMalaysia), which gained control of the state of Terengganu and retained its hold on the state assembly of Kelantan.

In the bitter election contest, the National Front’s control of the media gave Mahathir an overwhelming advantage. More than 85 percent of political ads and news reports before the election were skewed toward the ruling coalition, according to a watchdog group. ”The overall impression is that the Malaysian media, especially the television, are completely and shamelessly on the side of the government,” Muzaffar Tate of Malaysian Elections Watch told the Associated Press in advance of the election. The result also points up the growing contrast between Malaysia and some of its neighbors. Malaysia responded to the Asian economic crisis with capital controls, a crackdown on political opposition and continued control over the media. However, within the ten-nation Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand all enjoy a free press and relatively open societies with freewheeling public debate and multi-party political systems. The mandates enjoyed by the ruling parties in those countries are the result of genuine debate in both the print and the electronic media. Whatever the outcome of the Malaysian polls it will be impossible for Mahathir to erase the fact that the result will seem tainted by the ruling party’s control over the press. Indeed, rather than looking to his neighbors for vindication, in the run-up to the election, Mahathir seemed to turn to authoritarian China for approval of his policies. Chinese premier Zhu Rongji was in Kuala Lumpur the week before the polls with blessings for Mahathir’s approach to both information and capital markets. Zhu said that foreign media criticism of Mahathir was unfair. “I said to Mahathir that his policy was correct,” Zhu said. Mahathir, who has governed Malaysia since 1981 and is Asia’s longest-serving elected leader, seems likely to use election results as further justification to continue his stranglehold on free expression. |

Malaysian Election Special: PART II

|

| Bangkok, November 22, 1999— Despite more than a year of political unrest and widespread calls for greater openness and press freedom, the Malaysian government is unlikely to change the rules of the media game during the current snap election campaign. And why should it? After all, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s National Front coalition enjoys a tremendous edge by controlling virtually the entire mainstream press.

Mahathir called the polls on November 12, leaving just 18 days of campaigning before the November 29 general election. The government’s overwhelming ability to intimidate the mass media, dictate coverage and enforce a self-censorship regime on most newsrooms raises doubt that Malaysia can enjoy free and fair elections. And the turmoil that resulted from the September 1998 arrest and subsequent prosecution of former Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim (on corruption and sodomy charges) seems only to have stiffened Mahathir’s resolve to leave the media shackled. Mahathir’s dominant political party, the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), and its coalition allies directly own or control the major newspapers, radio and television stations in the country, making it virtually impossible for alternative voices to gain widespread access to the public. Meanwhile, government officials are taking full advantage of the tilted media playing field to tout their own accomplishments. As one local journalist put it: “Suddenly ministers who have never been quoted before in the media are appearing and essentially campaigning using their government positions.” Bureaucratic barriers The sweeping Printing Presses and Publications Act of 1984 allows the government to shut down so-called subversive ublications and requires publishers to renew printing licenses every year. The licenses dictate the language each publication is allowed to use (English, Malay, Chinese or Indian, to reflect the racial mix of the country) and the frequency with which they are allowed to publish.. On May 3 of this year, World Press Freedom Day, 581 Malaysian journalists signed a petition calling for the repeal of the act. The petition was presented to Deputy Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi who told the journalists, “I shall read it. I will let you know.” They are still waiting to hear from him. Independent journalists and publishers have found it nearly impossible to secure licenses to operate daily newspapers under the act, especially since a 1987 crackdown in which Mahathir shuttered several newspapers and moved Malaysia sharply to the right. There are a few small, independent weekly tabloids, and one major political party newspaper, Harakah, the party organ of PAS, the Islamic party, has mushroomed in popularity since Anwar’s arrest by publishing opposition-oriented stories. But despite its success, Harakah is a party organ rather than an independent newspaper. Forget TV Meanwhile, critical voices are virtually excluded from electronic media. There are two private television stations, but both have close ties to the government and are unlikely to give much coverage to the opposition. And even before elections were called, the government announced that the opposition would have no access to the state-owned Radio Television Malaysia, the country’s oldest TV station. Speaking in July, Deputy Information Minister Suleiman Mohamed said opposition parties had been allowed to use state TV channels to voice their policies during past elections but often broadcast “disturbing” material. Suleiman suggested that opposition parties wanting access to television could buy a station of their own and apply for a broadcast license. At times, the government’s efforts to shut out opposition voices has taken on absurdist tones. Entrepreneur Development Minister Mustapa Mohamed told Parliament that his ministry would revoke the licenses of taxi drivers who criticize the government. Mustapa said cabbies had been warned not to play tape recordings of anti-government speeches or display pictures of opposition leaders in their vehicles, according to the official Bernama news agency. “Don’t expect the media to be fair,” wrote journalist Steven Gan in an editorial published Wednesday in Malaysiakini.com, a new alternative news website launched this week in Kuala Lumpur . “[There is] not a ghost of a chance. The media is notorious in distorting news — sometimes it is subtle, at other times, more blatant. It is especially true now that the elections are around the corner.” Democracy online? Gan,who formerly worked in the mainstream press, is providing alternative news coverage online, taking advantage of the fact that Malaysia has few restrictions on the Internet because of Mahathir’s vision of turning the country into a center for high-tech research and investment. But Gan says it will take years before the Internet can be an effective mass medium to counter the power of the major media. “Like it or not, the Internet is only getting through to a minority of the voters,” said Gan. “A huge majority still depend on mass media for their news. Which is why the elections will be unfair.” Many journalists who work in this environment are frustrated by the compromises they have to make. In the aftermath of the Anwar affair, a large number of reporters reportedly left their jobs at major dailies to protest restrictions placed on them by pro-government supervisors. A senior editor at a major daily said recently, “For me it is always a battle to get a story into the paper. You have always to think about political considerations.” Many journalists fear their phones are tapped; most refuse to be quoted on the subject of press freedom or working conditions at their papers. “We are all afraid of losing our jobs if we go too far,” said one reporter. “It is not worth the risk.” Saint Murray’s passion For those who do take the risk, there is always the cautionary example of Murray Hiebert. In September, Malaysia became the only Commonwealth country in half a century to jail a reporter for contempt of court when Hiebert, at that time Kuala Lumpur bureau chief for the Far Eastern Economic Review, was sent to prison for four weeks as a result of a story he wrote that was critical of the Malaysian judiciary. The ordeal of the two year trial and appeals process — during which Hiebert was barred from leaving the country — made him Malaysia’s press freedom poster child. “Why are they doing this?” Hiebert asked rhetorically one afternoon in his office before he lost his appeal. “I think they want to send a message to reporters not to go too far in this country.” [CLICK HERE for Hiebert’s exclusive essay for CPJ.] This oppressive media environment makes it almost certain that the ruling coalition will be returned to power on November 29 and that Mahathir, Asia’s longest-serving elected leader, will continue to dictate the direction his country will take. Until now, Mahathir’s legitimacy has been based on his ability to guarantee political and economic stability. Papering over Malaysia’s ever-widening political cracks by muzzling the press will help neither the prime minister’s mandate nor Malaysia’s future prosperity. A. Lin Neumann is the Asia program consultant at CPJ. |

Malaysian Election Special: PART IIIA Matter of Debate

|

| Washington, DC, November 22, 1999 — I’ve become quite an expert on Malaysian tourist spots over the past two years. That’s because a local judge sentenced me to three months in prison for “scandalizing the court” in a magazine article that I wrote in 1997. While my appeal wound its way through the Malaysian legal maze, I was forced to remain within the borders of peninsular Malaysia.

My problems began in early 1997 when I wrote an article in the Far Eastern Economic Review, a news weekly published in Hong Kong by Dow Jones & Co, about a mother who was suing the International School of Kuala Lumpur for $2.4 million. She mounted the suit because fellow students had kicked her 17-year-old son off a debating team for alleged cheating. I used this case as an example to demonstrate that Malaysia had become almost as litigious as the United States. I paid a heavy price for that piece: on October 11, 1999, I finally got my passport back after completing 27 months under “country arrest” and 30 days in prison. In many Commonwealth countries, including Malaysia, private citizens can bring contempt of court charges against other individuals. In my case, the plaintiff was the wife of an Appeal Court judge. She filed her case with a High Court judge who found me guilty of contempt of court and sentenced me to three months in prison. I appealed the verdict, but had to wait two years for a hearing, during which time the courts held my passport as a condition of bail. In the end, the Appeal Court upheld my conviction, but reduced the sentence to six weeks. Prison officials cut my term by one third for good behavior. Although my case was unique, it has implications for other journalists working in Malaysia. The sentencing judge stated quite clearly that he was making an example of me because of his frustration with previous criticisms of the Malaysian legal system. “In my view, for far to long there appears to be unabated contemptuous attacks by and through publications or the media on the judiciary,” the judge said. “It is high time that our judiciary shows its abhorrence to such contemptuous conduct . . .” IÕm not the only journalist in Malaysia who has faced legal intimidation because of his work. A colleague from The Asian Wall Street Journal, which like the Review is owned by Dow Jones, is being sued for millions of dollars for alleged comments he is said to have made about the Malaysian judiciary in an interview with International Commercial Litigation, a magazine published in London. In two other suits, The Asian Wall Street Journal is being sued by businessmen close to the Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad. One of them is the prime minister’s son, Mirzan Mahathir. The damages sought total several hundred million dollars. And the threats don’t end there. A local journalist with The Star, a local newspaper owned by a Chinese political party in Malaysia’s ruling coalition, was threatened with a contempt of court suit when she wrote about one of the law suits facing Dow Jones. The message for journalists is hard to miss: you risk bankruptcy and prison if you write about political and economic developments in Malaysia. Is it any wonder that Malaysian editors and journalists increasingly censor themselves to avoid lawsuits? Fortunately, Malaysian prisons aren’t nearly as violent as US prisons, or as overcrowded and run down as jails in many developing countries. The most shocking thing for me was the abrupt loss of freedom. You have to struggle to keep up hope when the prison door clinks shut behind you. And it isn’t easy to learn to sit on the floor stripped to the waist half a dozen times a day while waiting to be counted by cocky guards, or to get used to using the doorless toilet when you get sick. But it would have been much harder for me endure the ordeal if the other inmates hadn’t adopted me into the prison family. On top of that, I was lucky that my jail term was relatively short. Still it was long enough for me to reflect on the value of press freedom and freedom of speech. I also gained new appreciation for those who have struggled to protect these freedoms. A few days after I was jailed I was taken to meet the prison director who let me watch while he looked through my file. It contained copies of protest statements by CPJ, Amnesty International, President Clinton and others. The fact that the world was watching helped guarantee that I had a relatively easy stay. When I walked out of prison on October 11, my heart ached for the roughly 100 journalists around the world who couldn’t enjoy my new-found freedom. I also knew I would never again take the work of groups like CPJ for granted. |