Amalia Pando was once a ubiquitous presence on Bolivian radio and TV, hosting some of the country’s most popular news and political commentary programs. At age 66, she’s still at it, but her audience is a sliver of what it once was.

Claiming that the government has blacklisted her from Bolivia’s major TV and radio networks, Pando now transmits her “Lucha Libre” political talk show via Facebook and YouTube, recording her program with a smartphone in a studio so cramped that guests wait their turn in a parking lot. Instead of a salary, she scrapes by on donations.

“This is what it’s come to,” Pando said in a recent interview with CPJ. “But what can I say? I have no other options.”

Over the past decade, some of Bolivia’s most prominent independent journalists have been forced from their jobs at major newspapers and broadcasters amid a government campaign to control the news media. Many of these journalists are still reporting and commenting on the news, but they now do so from fledgling websites and online TV and radio stations that reach a far smaller audience.

They’re also earning a lot less money.

“They’ve lost the capacity to make a living off of their profession,” says Pablo Ortiz, a reporter at El Deber, Bolivia’s largest-circulation newspaper, which is based in the eastern city of Santa Cruz.

Meanwhile, nearly all of Bolivia’s biggest news outlets have either adopted a pro-government line or have softened their coverage of President Evo Morales, as CPJ has reported. This gives Morales a huge advantage as he seeks a controversial fourth consecutive term in the October 20 presidential election, according to reporters, editors, and press analysts who spoke with CPJ during a trip to Bolivia in September.

The Morales government “has a monopoly where it matters: on TV and radio,” said Gonzalo Mendieta, a lawyer and political commentator in the capital city of La Paz. “In terms of political freedom, it is very disturbing.”

Bolivia’s Communications Ministry did not respond to numerous calls and WhatsApp messages from CPJ seeking comment.

Bolivian journalist Raúl Peñaranda is one of these media refugees. A former Associated Press reporter and Nieman fellow, Peñaranda helped found the independent La Paz daily Página Siete in 2010. He edited the newspaper for the next three years but resigned in 2013 amid a government smear campaign against him and the paper.

He now edits the independent news website Brújula Digital. It is registered as a non-governmental entity rather than as a media organization which, on occasion, has helped it avoid government harassment. But Peñaranda says the audience is far smaller.

“There are still some independent newspapers and web sites, but they don’t have as much impact,” he told CPJ. “We are on the margins.”

In some cases, Peñaranda says, government officials have threatened stations with tax audits or advertising boycotts unless independent journalists were taken off the air.

Andrés Gómez, one of Bolivia’s best-known radio journalists, said that he was forced out at the private Radio Compañera station in La Paz in December 2016, after the Communications Ministry threatened to pull government advertising – a vital source of income for many Bolivian news organizations – from the station.

“The message was: you can have either Andrés Gómez or you can have advertising,” Gómez, who now teaches journalism at the Bolivian Catholic University in La Paz, told CPJ.

In May, Juan Pablo Guzmán, host of the news program “Hora 23” on the private Bolivisión TV station, resigned after he was instructed by his supervisors to serve up softball questions during interviews with government officials.

“Many of them arrive for interviews with a list of questions that they want you to ask that have been OK’d by the station,” Guzmán wrote on Facebook after he resigned.

He added that Bolivisón and other TV stations had “mortgaged their dignity” by adopting a pro-government editorial line in exchange for state advertising.

In a few cases, journalists have not only left their jobs – they’ve left the country.

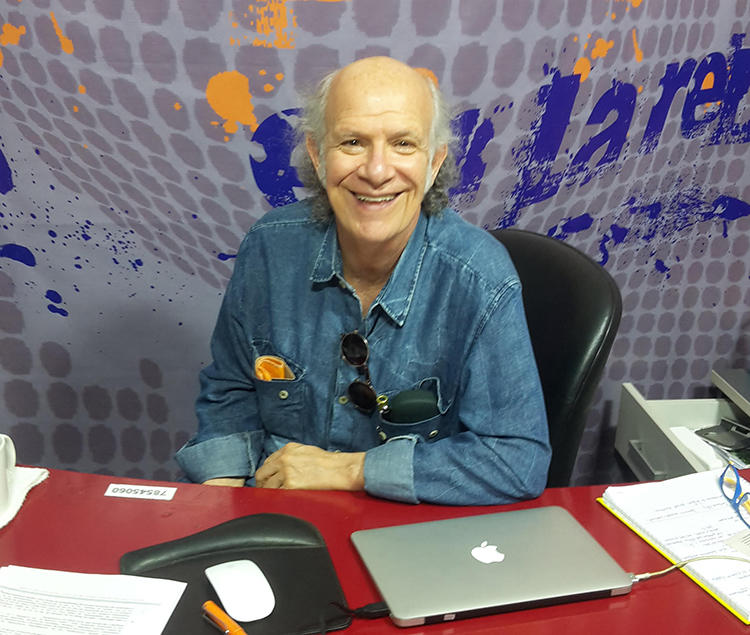

Among them is Carlos Valverde, a best-selling author who hosted widely watched news and interview programs on national TV and radio stations beginning in the early 2000s. He was initially thrilled by the 2006 election of Morales, the country’s first president of indigenous descent, but Valverde’s reports soon began to focus on government corruption.

Over the past decade, Valverde claims that the government pressured station managers to fire him or otherwise force him out. Valverde ended up working at local stations in Santa Cruz, and he kept breaking stories.

One of his biggest scoops was about an influence-peddling scandal in which Morales’ then-girlfriend, Gabriela Zapata, allegedly helped secure $500 million in government contracts for a Chinese engineering firm that employed her. Later, the unmarried Morales admitted that he had fathered a son with Zapata.

“I worked on that story for 10 months but my life became tremendously complicated,” Valverde told CPJ in an interview at his house, which doubles as a recording studio.

Angry government officials blamed Valverde and other independent journalists for what they claimed was a smear campaign against the president. After being tipped off that he was about to be arrested, Valverde fled to neighboring Argentina in May 2016. In Buenos Aires, he sold copies of his books to pay rent.

Valverde returned to Bolivia 16 months later but said he had been blacklisted by most stations in Santa Cruz. Now, he produces most of his reports and political commentary alone and uploads the material to Facebook and YouTube. He also has more than 200,000 followers on Twitter. It is a platform, but it’s a far cry from working in mainstream media.

“There’s no comparison,” he says. “I used to have a nationwide audience but now my viewership is abysmal.”

Even so, Valverde shakes his head when asked if the Morales government has achieved its goal of muzzling independent journalists.

“If the government would have managed to shut us up, it would have won,” Valverde said. “But we are winning because we are continuing to speak out.”

[Reporting from La Paz and Santa Cruz, Bolivia]