For the second year in a row, Turkey was the world’s leading jailer of the press, with 40 journalists behind bars, according to CPJ’s annual prison census. Authorities continued to harass and censor critical voices, firing and forcing the resignation of almost 60 reporters in connection with their coverage of anti-government protests in Gezi Park in June. The government tried to censor coverage of sensitive events, threatened to restrict social media, and, in one case, used social media to wage a smear campaign against a journalist. Peace negotiations between the government and the jailed leader of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, did not result in the expected release of Kurdish journalists. Legal amendments undertaken by the government did not result in meaningful reform of anti-press laws. In March, the Turkish Parliament began examining a bill known as the “fourth reform package,” aimed at aligning the country’s laws with international standards. The bill, adopted in September, introduced modest advancements, such as limiting the scope of a provision of the anti-terror law—”making terrorist propaganda”—that has been used against journalists, especially those who had reported on opposition parties. But the amendments did not address one of the most problematic articles of the penal code—”membership of an armed organization”—under which more than 60 percent of the imprisoned journalists in Turkey as of December 1, 2013, were charged. The jailing of journalists, the conflation of criticism with terrorism, and the government’s heated anti-press rhetoric, which emboldened prosecutors to go after critics, marred Turkey’s press freedom record and thwarted its aspirations to be regarded as a regional leader and democratic model.

Turkey

» Turkey continues to be the world’s leading jailer of journalists.

» Dozens of reporters fired in the aftermath of June anti-government protests.

For the second year in a row, Turkey was the world’s leading jailer of the press, with 40 journalists behind bars, according to CPJ’s annual prison census. Authorities continued to harass and censor critical voices, firing and forcing the resignation of almost 60 reporters in connection with their coverage of anti-government protests in Gezi Park in June. The government tried to censor coverage of sensitive events, threatened to restrict social media, and, in one case, used social media to wage a smear campaign against a journalist. Peace negotiations between the government and the jailed leader of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, did not result in the expected release of Kurdish journalists. Legal amendments undertaken by the government did not result in meaningful reform of anti-press laws. In March, the Turkish Parliament began examining a bill known as the “fourth reform package,” aimed at aligning the country’s laws with international standards. The bill, adopted in September, introduced modest advancements, such as limiting the scope of a provision of the anti-terror law—”making terrorist propaganda”—that has been used against journalists, especially those who had reported on opposition parties. But the amendments did not address one of the most problematic articles of the penal code—”membership of an armed organization”—under which more than 60 percent of the imprisoned journalists in Turkey as of December 1, 2013, were charged. The jailing of journalists, the conflation of criticism with terrorism, and the government’s heated anti-press rhetoric, which emboldened prosecutors to go after critics, marred Turkey’s press freedom record and thwarted its aspirations to be regarded as a regional leader and democratic model.

For the second year in a row, CPJ found that Turkey was the leading jailer of journalists. Most of those behind bars are Kurdish, charged under vague anti-terror laws.

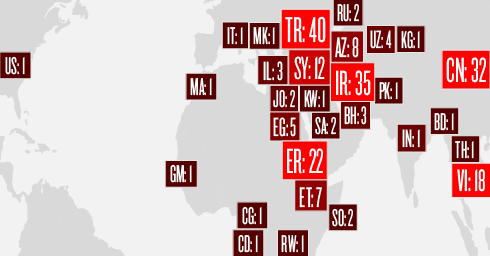

| Azerbaijan: 8 Bahrain: 3 Bangladesh: 1 China: 32 Democratic Republic of Congo: 1 Egypt: 5 Eritrea: 22 Ethiopia: 7 Gambia: 1 India: 1 Iran: 35 | Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories: 3 Italy: 1 Jordan: 2 Kuwait: 1 Kyrgyzstan: 1 Macedonia: 1 Morocco: 1 Pakistan: 1 Republic of Congo: 1 Russia: 2 Rwanda: 1 | Saudi Arabia: 2 Somalia: 2 Syria: 12 Thailand: 1 Turkey: 40 United States: 1 Uzbekistan: 4 Vietnam: 18 |

In June 2013, Ankara Mayor Melih Gökçek began an inflammatory Twitter campaign against a BBC reporter. Gökçek called Selin Girit, a reporter for BBC's Turkish service, a traitor and a spy, in apparent relation to the BBC's coverage of anti-government protests.

Paradoxically, the mayor used Twitter to target the journalist while Turkish authorities have called the social network a "menace." Turkish citizens are increasingly getting their news from the Internet because the space for independent information in the traditional media has shrunk.

At least 22 journalists were fired and 37 were forced to quit in connection with their coverage of anti-government protests in Gezi Park in June, according to the Turkish Union of Journalists. Police used tear gas and water cannons to disperse protesters and journalists covering the demonstrations. The union did not say who gave the order to fire journalists or force them to resign.

The personnel moves related to Gezi Park were the culmination of years of repressive policy by the government of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Hasan Cemal

The leading columnist was fired from Milliyet a few weeks after Erdoğan, in March 2013, criticized the newspaper's coverage and Cemal's work in particular. The paper had published leaked minutes of a meeting between the PKK leadership and deputies from the pro-Kurdish BDP party. Cemal had written in support of Milliyet's decision to publish the minutes.Yavuz Baydar

In July 2013, Baydar, who often contributes analysis and opinion on press freedom to international media, was fired from his longtime position as ombudsman at the pro-government daily Sabah. The dismissal came after Baydar wrote an article reportedly saying that an ombudsman should be able to operate independent of the publication's editor-in-chief. The column was not published. Baydar had criticized authorities' reaction to massive anti-government rallies, known as the Gezi Park protests.Can Dündar

The veteran journalist was fired from the daily Milliyet in late July 2013, shortly after the dismissal of his editor-in-chief, Derya Sazak, and the appointment of a new editor. In his personal blog, Dündar said he had been informed of his dismissal via a phone call by Milliyet's owner, Erdoğan Demirören. Dündar said he had expected the action after the newspaper froze his column for three consecutive weeks in apparent retaliation for his reporting and commentary on the Gezi Park protests and the government's harsh dispersal of the rallies.Mustafa Balbay, a columnist with the leftist-ultranationalist daily Cumhuriyet, was imprisoned for almost five years in connection with his alleged involvement in Ergenekon, a shadowy conspiracy that authorities claimed was aimed at overthrowing the government in a military coup.

Balbay was detained in March 2009. In August 2013, he was sentenced to 34 years and eight months in prison. At least 19 other journalists were sentenced in the same case.

On December 9, Balbay was released from prison after Turkey's Constitutional Court said he had been held without a conviction for an unreasonably long time. The court also said that by having jailed him—an elected member of Parliament—authorities had violated the people's right to be represented.

Balbay's release stirred hope among press freedom advocates that more journalists held on similar charges and in similar conditions could be released.