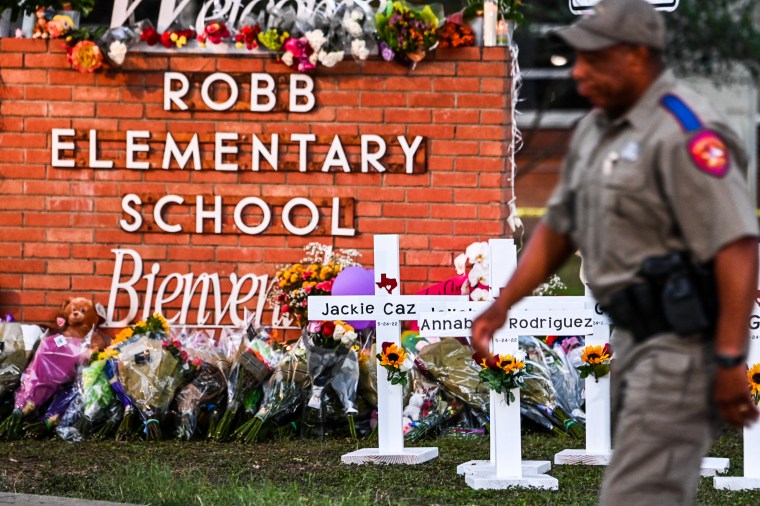

False narratives, threats of arrest, and a biker group blocking access. These are just a few of the challenges journalists have faced while covering the aftermath of the May 24 shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas.

Threats to press freedom are hardly the main story in Uvalde, where police failed to stop the 18-year-old gunman from killing 19 students and two teachers. But efforts by the authorities to impede the free flow of information about the tragedy ultimately do a disservice to the local community in its search for answers.

To learn more about what journalists faced, CPJ spoke by phone with Guillermo Contreras, a staff writer at the local San Antonio Express-News and Zach Despart, a politics reporter at state-wide non-profit news website Texas Tribune, who have covered different aspects of the shooting. The interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

CPJ left a voicemail requesting comment from Uvalde school district’s police chief, Pete Arredondo, but did not receive a reply. Chris Olivarez, the Texas Department of Public Safety’s spokesperson for the south Texas region, did not respond to CPJ’s email.

Guillermo Contreras, San Antonio Express-News reporter

Police in Uvalde threatened to arrest you and other journalists who went to school district headquarters June 1 and 2 to interview the Uvalde school district’s police chief, Arredondo. What’s your explanation of this?

To have police come along and tell us that you will get arrested for doing your job, you know, that’s troubling to me.

As more details are coming out, there’s been a growing sentiment [among law enforcement] that we’re out to get the police – to me that’s just not true. We’re trying to just get the truth about what transpired.

There have been so many shifting narratives about what happened — and that does not help. Local officials don’t know how to handle this mass attention. There’s frustration with us. But no matter how polite we are — we come in and ask if there is a statement they can print out or point us to — we’re [stonewalled].

It’s not like I’m not going into somebody’s crime scene. We’re going into a public building where someone can get answers as quickly as we can.

Police have also allegedly coordinated with local biker groups to impede journalists, including from your newspaper, from reporting at funerals.

Some cops are more aggressive than others. It’s left to the police’s discretion. You don’t want to test that because you have your job to do and you don’t want to become part of the story — that’s not my intent. My intent is to cover and inform people.

We saw our [San Antonio Express-News] photographers being harassed by bikers who claimed that police asked them to help do this. Even when the photographers would go up to residents, just to speak to them to make sure they were comfortable, the bikers would go up to them and say, “You don’t have to talk to them.” That’s not something we’ve really seen before in this type of situation.

Biker groups are prevalent in some small towns [in Texas], they’ll have little local chapters. It’s only [recently] that we’ve started to see these types of incidents. It just seems like they’ve gotten together and decided that they are trying to be obstructive.

There seems to be genuine concern among locals in Uvalde that some reporters are being too invasive in their coverage. What has been your experience on the ground?

No one wants to approach someone who’s just lost a loved one. It’s not something that we look forward to. It’s very, very sad. These are people in their most vulnerable times. But we do have to explain and try to tell their stories. You have to be prepared for different reactions and know when to move on.

You also covered the 2017 Sutherland Springs shooting, when a gunman killed 26 people at a Texas church, and its aftermath. What has stood out to you about this recent shooting?

Following the mass shooting in Sutherland Springs in 2017, there were different agencies at the scene but they were all putting out information in unison. You expect some information to be wrong initially. But when officials come back and change their stories so quickly — that’s a huge difference.

We had a teacher who was practically dying of guilt wondering if she had left a door [open before the gunman entered the school, as Texas officials initially claimed]. As we saw, [law enforcement acknowledged] she did close it. That erodes public confidence when [law enforcement changes its story so quickly].

In normal times, reporters will try to compete against each other for stories. At this point, following a mass shooting like this, you’re just trying to get out there and avoid complications with police, just to try and get answers and accountability. Our role is to try and get answers with the hope that it will lead to accountability.

Can you talk about the emotional impact of covering these events?

It can be difficult to talk about. The other day I was walking into work and I got a call from an attorney who is working on a case for a survivor [of the Uvalde shooting]. He told me a story about what had happened in detail and I was just picturing it in my head. [The attorney] was at the point of tears. I had to go sit down.

Hearing these details, I can’t help thinking that my daughter is the same age, and the same grade — it could happen to any of us. It takes a toll emotionally.

At the same time, I have to put my feelings aside. I’m not a columnist, I don’t do opinion. I have to see if I can gather some of the facts and that’s what I’m striving for. You’ve got to put that aside and put the feelings down and go forward.

I’ve been in the news business for more than 25 years and have covered three or four [mass shootings] — it’s never easy, you know. I hate to say it but it’s kind of the inevitable nature of the job.

Zach Despart, politics reporter at the Texas Tribune

Local authorities have been, at best, avoidant of media, and at worst actively tried to obstruct coverage. What has it been like to try to cover the police response amid these hurdles?

One of the things we tried to stress in our reporting is yes, there has been a lack of transparency from local officials with journalists, but we’re far less concerned about that and far more concerned about how our residents — the people who are constituents of these local officials — are not being served because of this lack of transparency.

For example, residents want to hear from Uvalde school police chief, Pete Arredondo, and they’re quite upset that Arredondo — the man who was the incident commander during the shooting, and whom the state police had said made the critical mistake of not ordering police to immediately confront the shooter, instead waiting more than an hour before the shooting was finally ended by law enforcement — has been quiet.

The fact that he has essentially been in hiding from public view for 10-12 days is quite upsetting to them and is sort of underlies that a lot of residents that I have interviewed expressed dissatisfaction with local law enforcement generally. They felt like they are not responsive to the community’s needs.

[Editor’s note: After CPJ’s interview with Despart on June 6, the Texas Tribune ran a lengthy interview with Arredondo.]

What, if any role has mis- or dis-information played in the news story?

In the initial two or three days after the shooting, the governor and state police had officially changed their narrative about what happened in the shooting [from saying police acted bravely to detailing their slow response to the shooting] in a way that was obviously frustrating for journalists because they always want to get it right. It was also frustrating for residents because they wanted to know whose fault it was and why it went wrong.

It affects the trust in the public and what state officials are saying when the official story changes.