Li Wenliang, a doctor in Wuhan who was reprimanded for warning colleagues of a new coronavirus earlier this year, used the messaging app WeChat to share his concerns on December 30, 2019, according to The Wall Street Journal.

“Be careful, our group chat can be suspended,” a contact responded, according to screenshots purporting to show the private exchange. CPJ could not independently verify the screenshots, which were widely cited in online discussions and media reports after Li sickened and later died from the COVID-19 disease.

On December 31, at least some posts involving the virus were already subject to censorship on Chinese platforms, according to a report published this month by Citizen Lab, which is based out of the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. China’s sophisticated censorship apparatus blocks foreign social media platforms, while requiring their local counterparts to monitor and control what their users are able to share. CPJ reporting suggests Chinese companies use automation and manpower to block topics that are perennially sensitive, as well as implement propaganda directives issued when news breaks.

Not all information about the ongoing public health crisis has been suppressed—related discussions were easy to find on Chinese social media this month, according to CPJ monitoring. But some posts remained subject to control, including a March 10 interview with another Wuhan doctor that was shared as an audio recording, translated into Korean, and even encoded by WeChat users to evade censorship, according to the China Media Project at Hong Kong University.

Citizen Lab’s report lists dozens of keywords that triggered censorship of posts on both WeChat and YY, a live-streaming platform, between December 31, 2019 and February 15, 2020. Citizen Lab says this restricted factual public health information, as well as opinions about the government’s handling of the outbreak. Cases of COVID-19 have since been confirmed in more than 110 countries, the WHO said in March.

CPJ requested comment on Citizen Lab’s findings from WeChat’s parent company Tencent via their website, and from YY via email, but received no response before publication. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Cyberspace Administration of China, and the Public Security Bureau in Wuhan did not respond to CPJ’s messages requesting comment.

CPJ interviewed Lotus Ruan, a Citizen Lab researcher who co-authored the report, via email in March. Her replies have been edited for length and clarity.

First off, what triggered your interest in analyzing social media censorship in China around the COVID-19 outbreak?

As a research lab focusing on digital technologies and human rights, Citizen Lab has been tracking Chinese social media censorship for years. The COVID-19 outbreak is one of the many events we track.

We noticed that discussions on the coronavirus outbreak started to trend on Chinese social media in early January. Meanwhile, we started to pick up censored keywords on YY and WeChat. As we gathered more data we decided to share our findings, as this is not just any event, but one that pertains to a global public health issue.

Chinese netizens are known for using wordplay as a workaround when keywords are censored on social media. Did you come across any during your research?

Some keyword combinations [that were censored] include sarcastic homonyms or word play related to COVID-19. One example, “virus of officialdom,” is a homonym of the Chinese phrase for coronavirus.

What are the implications for journalists trying to report on the outbreak and the public’s right to information?

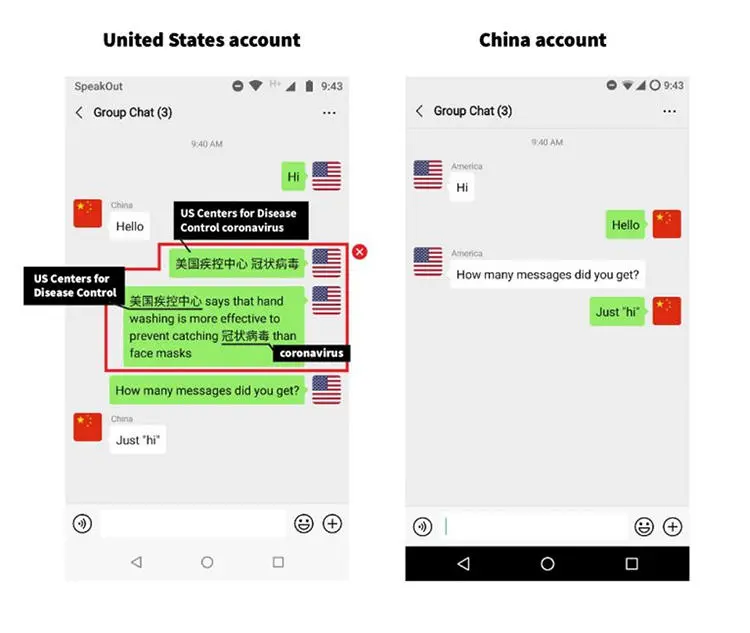

WeChat implements censorship on China-registered accounts. When reporters (or any users) register their WeChat account with a Chinese phone number, they will be subject to censorship, even when they move outside mainland China and unlink the original phone number.

Moreover, censorship is conducted “silently,” in the sense that users will not know their messages are censored unless they double check with recipients. Such a system can potentially hinder communications among reporters who try to discuss work or share notes with their colleagues via WeChat.

Your report says Chinese authorities vowed to rid the internet of rumors about the epidemic that they say will cause public fear and chaos. Do you think China would have been able to control the spread of the virus without censorship?

It is arguably reasonable to moderate content to prevent the spread of misinformation and disinformation. The question is moderation by whom, and according to what standard. Content moderation needs to be done with transparency and accountability. In the case of YY and WeChat, we have not seen transparency or accountability from either company.

Censorship is an important part of China’s propaganda apparatus, which aims to manage public opinion. Broad censorship of neutral and even factual information related to the virus might have limited the public’s ability to share and discuss knowledge of the prevention of the disease.

We do not measure China’s ability to control the spread of the virus. Whether China—or any country for that matter—is able to control the virus and whether it censors information related to it are not mutually exclusive.

Do you think that restricting communication related to information about COVID-19 contributed to the spread of misinformation online?

While we don’t have data to measure the correlation, the wide scope of censorship we observed from YY and WeChat is problematic, because blocking broad information during a health crisis can limit the public’s ability to stay informed and protect themselves.

The Wall Street Journal reported recently that a Singapore-based subsidiary of YY has begun exporting the system it uses to moderate content. Are you aware of any such systems being deployed elsewhere?

We have not come across foreign platforms using Chinese filtering technologies. However, the case of WeChat is worth studying, as the implications of censorship on WeChat go far beyond its impact on China-based users.

Because of the way it implements censorship, WeChat’s content controls affect not just users in China but also those who emigrated from China. If users only read information on WeChat even after they move abroad, their perception of news events and local politics may be heavily skewed based on how WeChat filters relevant information.

Were any English keywords about the coronavirus outbreak censored?

We didn’t find any during our testing period for this report. However, in past reports we observed that Chinese social media platforms censor content in other languages. WeChat also censors content in English, and in some cases, Hindi and Tibetan as well.

In our study of keyword censorship on China’s mobile gaming platforms, we found that some platforms censor Japanese and Korean keywords.

How does China’s approach to censorship compare with other countries around the world?

The censorship apparatus in China is sophisticated because, on one hand it is conducted through a system of intermediary liability, and on the other hand, laws and regulations on content are vague and broadly defined. Companies are expected to share the burden of controlling content on their platforms, but also to figure out what specific content they should censor. As a result, private companies often end up self-censoring to play safe.

Authorities or private companies may lift censorship around some keywords as they become less sensitive or attract less public attention, while continuing to block others. Censorship on Chinese social media is dynamic—therefore it is important to continue tracking how information is controlled.

How can the authorities in China and elsewhere learn from this tragedy?

Keeping the public informed with accurate information related to disease prevention helps them to be better prepared. While it may be reasonable to moderate information in a moment of crisis to keep public fear and misconceptions in check, it is important to do so with transparency and accountability.

CPJ’s safety advisory for journalists covering the coronavirus outbreak is available in English, Español and فارسی.

CPJ China correspondent Iris Hsu contributed reporting from Taiwan.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: The name of the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy has been corrected in the third paragraph.]