How much should journalists hold back when covering terrorism in Europe?

By Jean-Paul Marthoz

European journalists are on edge. Since the brutal execution of eight colleagues at the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo on January 7, 2015, they have become acutely aware that they are in the firing line of extremists.

“Journalists will not cede to fear,” said Ricardo Gutierrez, the European Federation of Journalists’ general secretary, after a second attack, on November 13, 2015, claimed the life of another journalist who was covering the Eagles of Death Metal concert at the Bataclan Theater.

Most vowed not to submit to such fears, though some (cartoonists, in particular) confessed at the time that they thought twice before filing a story or writing a column that might trigger the ire of terrorists.

Their unease also stems from a nagging feeling that authorities, despite their public commitment to defending free speech and a free press, look at journalists with a degree of suspicion, as if they are a hindrance in the fight against terrorism.

The question facing journalists in such an environment is: At what point does self-restraint become self-censorship?

EU member states do not go as far as Turkey President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who rushes to denounce critical reporters and columnists as accomplices of terrorism. But former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s characterization of the media as “the oxygen of terrorism” is treated as dogma by many in European security circles. By describing the situation as a “war,” government officials expect the media to toe the line.

The risk was highlighted in a January 26, 2016, report by the Council of Europe’s Committee on Political Affairs and Democracy, which noted that “combating terrorism and protecting Council of Europe standards (respect for human rights, rule of law and common values) are not contradictory but complementary… While acknowledging the need for member States to have access to sufficient legal instruments to combat terrorism efficiently, the Assembly warns against the risk that counterterrorism measures may introduce disproportionate restrictions or sap democratic control and thus violate fundamental freedoms and the rule of law, in the name of safeguarding State security.”

Little by little, drop by drop, the media integrate these concerns into their news routines and some even anticipate or go beyond security service orders or recommendations. Though they may reject any notion of self-censorship, “caution” has become the byword of “ethical” or “responsible” journalism.

After the killing of a Catholic priest on July 26, 2016, at Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray, in Normandy, the leading French news channel BFM TV decided to stop showing pictures of terrorists. “We want to avoid putting terrorists on the same level as their victims whose photos we do broadcast,” said BFM TV news director Hervé Béroud. The 24-hour news channel banned in particular a photograph of one of the killers, “a smiling beautiful young kid who had just cut a priest’s throat,” Béroud added.

France’s newspaper of record, Le Monde, took a similar approach. “Following the Nice attack (on July 14) we will no longer publish photos of killers in order to prevent potential effects of posthumous glorification. Other debates on our practices are going on,” wrote its editor-in-chief, Jérôme Fenoglio. The decision was limited to photos taken by terrorists themselves or drawn from their daily life before they committed attacks. The ban did not include photos that had clear news value, Le Monde added.

Europe 1, one of the top French radio stations, went even further by deciding not to name the killers. “Such decision appears laudable, but it is unlikely that one of these terrorists was radicalized while reading Le Monde,” Catholic University of Louvain professor of journalism ethics Benoit Grevisse said. “It ignores the reality of social media and internet sites. Besides, it contradicts a founding value of journalism ethics: the obligation to look for and publish the truth on matters of public interest. To make of non-publication an a priori implies that elements of information like names or faces would never be of public interest.”

Although other newsrooms reaffirmed their right and perceived duty to show and name alleged terrorists, these initiatives reveal the ethical dilemmas the mainstream media faces in the coverage of terrorism. Appeals for restraint and responsibility have proliferated since the wave of attacks in France and Belgium, mainly due to the fact that wall-to-wall coverage of these dramatic events led to a number of egregious mistakes and missteps. A few media outlets, and especially 24-hour news channels, crossed red lines in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack and during the hostage-taking at the Hyper Cacher store in Paris a few days later. On February 12, 2015, the French audiovisual higher council, known as CSA, issued a strong statement highlighting 36 “failings” in the media’s coverage of these events, in particular the broadcasting of information on the deployment of police forces that might have been watched by the terrorists as well as the revelation that people were hiding in parts of the buildings where the terrorists were still active.

Likewise, in March 2016, a French newsweekly revealed that the Belgian police had found the DNA of Salah Abdeslam, a participant in the November 2015 attacks in Paris, and who was the most wanted fugitive in Europe, during a raid on a house in a Brussels suburb — a leak that could have tipped off Abdeslam. In another incident, the transmission truck of a major Belgian private TV channel was pre-positioned close to the house where Abdeslam was hiding before the police had even started its operations.

“They offer the security of my staff on the altar of ratings,” the director of Belgium’s judicial police, Claude Fontaine, said during a TV debate.

After each attack, media outlets have been slammed, including from inside the profession. On August 8, 2016, three weeks after the Nice slaughter, prize-winning columnist and writer Jean-Claude Guillebaud published a damning column titled, “When the media become crazy.”

There is no doubt that some in the media went into overdrive and lost sight of the rules of the ethical highway. But if the danger to journalistic integrity lies in overhyping terrorist acts, it also stems from the conviction some hold that the press should be part of the general fight against terrorism.

There is little doubt about where journalists stand. After Paris, Brussels, and Nice, editorials, articles and broadcasts were universally filled with the strongest condemnation of these heinous acts. However, there is a danger that such concerns about potentially endangering public security or the desire to be in sync with a shocked public could lead journalists to defang their legitimate coverage of counter-terrorism and minimize their watchdog role in the name of national unity or the common good.

A few Belgian journalists grumbled when on November 22, 2015, the Belgian police “invited” the press to go silent during a raid against suspected terrorist hideouts in Brussels, but the media complied and instead ran photos of cats on their websites until it was considered safe to report on the raids. “Are Belgian media more responsible or more servile than French ones?” asked Le Monde‘s Brussels correspondent, Cécile Ducourtieux.

“Restricting the live coverage of police operations is considered legitimate as long as they do not constitute an act of news censorship,” Jean-François Dumont, deputy general secretary of the Belgian Association of Professional Journalists, said.

Belgian journalists remained on the scene and continued filming without broadcasting live or posting online precise details on the location of the raids. But a few hours later they provided full coverage of the events.

“The media have a duty to monitor police actions; they have a duty of inventory,” explained Jean-Pierre Jacqmin, the head of news for Belgium’s Francophone public broadcaster RTBF.

In fact they have of duty of going beyond “fusion journalism,” which naturally prevails in the first hours following an attack and tends to be driven by empathy for the victims, calls for national unity, admiration for the rescue teams, and respect for the security forces’ mission.

The general consensus among journalists is that feelings of grief and humanity cannot supersede the press’s duty to report the facts — including shocking or inconvenient facts. Some politicians are quick to stigmatize journalists who are out of step and insist on asking “Why?” at the risk of breaking the nation’s emotional communion. During a November 26, 2015, Senate Q&A session, French Prime Minister Manuel Valls declared that he was “weary of those people always looking for excuses or cultural and sociological explanations” for the attacks. On January 9, 2016, in an homage to the victims of hostage murders at the Jewish store Hyper Cacher, Valls drove the point home. “Explaining is already a little bit like excusing,” he said. His approach, however, was contradicted in a March 2016 report commissioned by the government after the November 2015 attacks. “Knowing the causes of a threat is the first condition to protect against it,” wrote the authors, a team of researchers at the prestigious Athena Alliance (a collective of social sciences researchers), using words that also define the journalistic ethos.

The point is that revulsion over the attacks does not absolve journalists of their duty to tell the facts and ask tough questions. “On the Opinion pages one factor taken into consideration was timing – judging when readers would be willing to engage with an idea that in the first 24 hours after the attacks may have jarred,” The Guardian standards editor Chris Elliot wrote on November 23, 2015, just after the Paris attacks. “The idea that these horrific attacks have causes and that one of those causes may be the West’s policies is something that in the immediate aftermath might inspire anger. Three days later, it’s a point of view that should be heard.”

Alain Genestar, the director of the glossy photojournalism magazine Polka, authored an editorial along those same lines in September 2016, defending the media’s right and duty to inform independently. “Every citizen is entitled to put in doubt the efficiency of the government’s security policy when the death toll is of 230 dead in 18 months,” he wrote. “Every citizen is entitled to ask explanations from the Interior minister who, after the Nice attack, was tight-lipped. Unity, in a true democracy, does not mean granting blind and deaf trust to a man, even to the President.” The headline of his editorial, “During the attacks democracy continues,” underlined that the response of democratic states, the methods they use, and their care not to enforce abusive exemptions from the rule of law and fundamental rights, is crucial to the fight against terrorism. Few journalists, however, focus on investigating stories that might question the effectiveness or the legality of police and intelligence agencies’ operations. Such issues are mostly left to researchers of human rights or civil liberties associations.

“Some journalists may fear being shut off from inside sources who provide them with tips on operations, arrests, or investigations,” Andrew Stroehlein, European media director at Human Rights Watch, said. “They may also be afraid of upsetting the public, who in times of crisis tend to trust the authorities and consider maverick journalists as unpatriotic or even as useful idiots of terrorism.”

The idea expressed by former Washington Post publisher Katherine Graham, that “news is the lifeblood of liberty,” is not unanimously shared. In the trade-off between liberty and security, most people, according to many surveys, would choose a restriction of freedoms and a security-first approach. In the wake of the July 14, 2016, “mad truck” slaughter on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice, which killed at least 84 and wounded hundreds, an Institut Français d’ Opinion Publique survey (IFOP) concluded that 81 percent of the French adult population agreed with the imposition of limits on the traditional liberal-democratic way of life to combat terrorism. “We are witnessing a form of democratic approval of a decline of democratic freedoms,” said Paris University professor François Saint-Bonnet.

Some authorities may also be tempted to abuse the argument of public security or police safety to defend controversial policies unrelated to the terrorist threat. In August 2016, Christian Estrosi, a leading member of the opposition center-right party and a former mayor of Nice, threatened to sue social media users who shared photos of a team of municipal police questioning a modestly-clad Muslim woman sitting on the beach. He claimed these photos, taken at the height of the controversy over the banning of the burkini, a full-body bathing suit, had led to threats against the agents.

Authorities are increasingly acting as if the threat of terrorism or public disorder could justify a number of exceptions to the freedom to report. In the Netherlands, the “public interest” or the risk to “public order” or “peaceful coexistence” was invoked to ban journalists from doing their most basic job when reporting on an issue of deep public interest: migration. In a number of Dutch small towns, the governments created a press ban to prevent journalists from covering public debates between the authorities and local residents over the opening of refugee centers. The authorities claimed the presence of cameras or reporters would inflame passions and derail efforts to discuss this controversial issue in a civil manner.

“In an open and democratic society, it is up to the media to decide what to report on, how to report and what methods to use,” the Dutch Society of Editors in Chief complained.

But Sander Dekker, the Dutch State Secretary for Education, Culture and Science, supported the decision in an answer to a parliamentary question, arguing the measure was “not disproportionate.”

Increasingly, democratic governments adopt public safety laws and measures that compromise the exercise of independent journalism. On June 30, 2015, the Spanish government put into force a Public Security Law, known as the gag law, which allows the imposition of heavy fines on anyone filming the police in action. Such laws, the Spanish government argued, are meant to protect the privacy and safety of security forces and their families. But human rights and press freedom groups complained that the law effectively undercuts the right of the press to monitor the behavior of the police and guaranteed impunity for any abusive act or violation of fundamental rights.

In April 2016, Axier Lopez, a journalist working for the Basque magazine Argia, was the first journalist to be fined under the Spanish law. He had posted on his Twitter account an “unauthorized” photo of police making an arrest. “Through these images it is possible to identify the officers taking part in the operation, with the risk that for the officers can result from their public identification,” the judge in the court case that followed said.

Likewise, in France, a “snoopers law” was put in force in July 2015, allowing the security services to intercept online conversations. The law does not exempt journalists and therefore poses a potential risk of intrusion in their legitimate work and compromises the confidentiality of sources, press freedom groups warned. The law “grants excessively large powers of very intrusive surveillance on the basis of broad and ill-defined aims, without prior judicial authorization and without an adequate and independent oversight mechanism,” according to the U.N. Human Rights Committee.

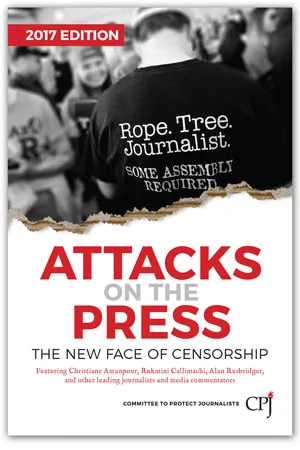

Amid the debate over the media’s – and, by extension, the public’s – right to know, few question the idea that terrorism is a major threat to democratic societies. Most in the media are aware of its dangers and of their responsibility not to provide terrorists with the “oxygen of publicity.” But terrorism is not only dangerous due to its violence against people who are often innocent civilians. It is also part of the killers’ efforts to portray democracy as an empty shell that can easily be broken by fear. Terrorists attempt to chip away or even dismantle what constitutes the essential guarantees of an effective and vibrant democracy.

As a result, journalists who are attempting to be circumspect and cautious in their reporting must also address the reality that independent watchdog journalism is necessary, now more than ever, to protect democratic states and their citizens from their own instincts to overreact – essentially, that a free press can act as a guardrail against abuses and restrictions, which could effectively lead targeted countries into the terrorists’ trap. Legendary rebel journalist I.F. Stone’s assertion could serve as a warning. “All governments lie,” Stone famously wrote in his 1967 book, In a Time of Torment, “but disaster lies in wait for countries whose officials smoke the same hashish they give out.”

As U.S. Senator J. William Fulbright advocated in an April 25, 1966, speech during the Vietnam War: “To criticize one’s country is to do it a service and pay it a compliment. It is a service because it may spur the country to do better than it is doing; it is a compliment because it evidences a belief that the country can do better than it is doing… Criticism, in short, is more than a right: it is an act of patriotism–a higher form of patriotism, I believe, than the familiar rituals of national adulation.”

Jean-Paul Marthoz is a Belgian journalist and writer whose recent book on journalism and terrorism was published by UNESCO. He teaches global journalism at the Université catholique de Louvain (Belgium) and is CPJ’s former EU representative.