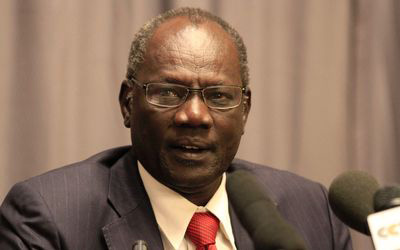

Last week, South Sudanese Information Minister Michael Makuei warned reporters in the capital, Juba, not to interview the opposition or face possible arrest or expulsion from the country. According to the minister, a lawyer by profession, broadcast interviews with rebels by local media are considered “hostile propaganda” and “in conflict with the law.”

Makuei’s remarks follow a recent interview conducted by the Juba-based, independent Eye Radio with a rebel leader at peace negotiations taking place in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. “We will not allow any journalist who is hostile to the government to continue to disseminate this poison to the people,” he warned local and foreign reporters at the press conference. While South Sudan’s interim constitution protects freedom of speech, Makuei told reporters to convey “a neutral position that does not agitate against the government.” He did not specify how they should do this.

Attaining a balanced perspective on the South Sudan’s political crisis has been challenging for reporters since it began three months ago. While reporters have access to rebel-controlled areas, local journalists told me, acquiring an interview with rebels suspicious of outsiders in restive areas is not easy. “Attaining access [to the rebels] is bad enough,” said one photojournalist who asked not to be identified. “Now trying to air their story may lead to even more challenges.”

Since January, the government of South Sudan has been in peace talks with a rebel group led by former Vice President Riek Machar after a conflict broke out in the capital on December 15 between forces loyal to Machar and those loyal to President Salva Kiir. Driven by political aspirations, the conflict soon took on ethnic dimensions, pitting the two most populous tribes, the Dinka and the Nuer, against one another.

Irrespective of what they write or broadcast, journalists of Nuer ethnicity are immediately perceived by authorities as siding with the rebels under the control of Machar, a Nuer, and cannot do their jobs, local journalists told me. Similarly, journalists from the Dinka tribe are targeted for their ethnicity in the rebel-controlled areas, the same sources said.

Fearing retribution, reporters of Nuer ethnicity are avoiding the government- controlled areas, freelance journalist Bonifacio Taban told me. The hardline stance of the government is making it more and more difficult for the local press to remain impartial. “The news in South Sudan is not balanced, it has become one-sided, the government side,” Taban said.

Oliver Modi, the chairman of the Union of Journalists in South Sudan (UJOSS), condemned Minister Makuei’s remarks, saying the public needs information from both parties in the conflict. “We need information from all sides–this helps reach decisions that can lead to peaceful negotiations,” he said in an interview with the U.S.-backed broadcaster Voice of America.

While there have been no substantiated reports of prosecutions of a journalist for airing the rebels’ views, the government warning is likely to deepen self-censorship, local journalists told me. UJOSS cited 20 incidents of harassment, attacks, and targeted looting against journalists in the first month of the crisis alone. For example, security agents confiscated two editions of the independent daily Juba Monitor in January, Managing Editor Michael Koma told me. Agents seized after printing one edition for publishing an article that criticized Kiir’s leadership and another edition for running a comment by a U.N. official that claimed the police had killed many ethnic Nuer citizens at Gudele Police Station, Juba. “We are very sad–these days, we self-censor to survive,” he said.

Government intolerance toward the views of opposition groups is not unusual in East Africa; where reporting a rebel group or opposition party’s stance is sometimes even a criminal offense. Radio France Internationale and Bonesha FM correspondent Hassan Ruvakuki spent 16 months in jail after he interviewed a leader of a rebel movement in Burundi. Originally sentenced to life in prison for “participating in terrorist acts,” the sentence was reduced on appeal in January 2013 to “participating with a criminal group.” In Uganda, police routinely harass journalists over opposition coverage and temporarily closed two media houses in May 2013 for publishing material from a dissident security chief within the ruling party. Since Ethiopia passed anti-terrorism legislation, even email exchanges with opposition groups who the ruling party deems to be terrorists can lead to a heavy prison sentence. Eleven journalists have been prosecuted under this legislation since 2011, according to CPJ research.

Prior to the peace agreement in 2005 between Sudan and South Sudan that paved the way for the latter’s independence in 2011, Sudanese media coverage of the rebels in the South was scant and extremely biased. Balanced coverage of the 22-year long conflict was impossible for the press in Khartoum, Sudan’s capital.

Press conditions may still be more tolerant in South Sudan compared to its restive neighbor, where newspapers are routinely censored or confiscated and reporters and editors harassed. But South Sudanese authorities’ growing intolerance toward a free press increasingly resembles the oppressive tactics of Khartoum–repression that led the South Sudanese to fight for their independence in the first place.