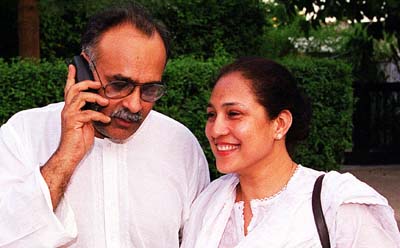

We released a statement Thursday–CPJ supports Pakistani journalists facing threats–about the decision of two Pakistani journalists to publicly announce the threats they had been receiving. Najam Sethi, editor of The Friday Times and host of a popular Urdu-language political program on Geo TV, and Jugnu Mohsin, also a Friday Times editor, said they had lived under threat for years but the level of danger had become so menacing in early 2011 that they were forced to leave Pakistan. A few months later, the two went public with the threats. Then, on Thursday, Sethi told us that he and Mohsin had decided to return to Lahore on Friday.

The two journalists were recipients of CPJ’s 1999 International Press Freedom Award. That year, they asked us to watch their backs. Sethi made the same request to us this year, and stressed the importance of international groups like CPJ and Human Rights Watch. “It’s rough out there,” he said. “One never knows whether the Taliban is gunning for you or whether the agencies are gunning for you. And sometimes you don’t know because one is operating at the behest of the other.”

Here is part of Sethi’s most recent message to us:

“Jugnu and I have decided to return to Pakistan and dig our heels in. Wednesday, I made a formal statement on my GEO television show regarding various threats to my family and me since 2007, but especially in 2011.

I wasn’t specific, but I said that the threats came from both state and non-state actors, including extremists. On the program, I said I had informed various media bodies at home and abroad about the specific nature of the threats but preferred not to say more for the moment. I said my family and I would hold certain organizations and persons, regardless of their sensitivity or rank, responsible in the event we were harmed in any way. I confirmed that the Interior Ministry had formally issued notice in 2011 to all police and intel organizations regarding the threats to my family and me.

In publicizing our decision, I referred to the recent case of Hamid Mir and said that all journalists should lodge complaints and bring such threats into the public domain. I added that at least two Pakistani journalists, one from Karachi and one from Quetta, had applied for asylum abroad because of similar threats to them.”

On December 20, Hamid Mir, a prominent television anchor and political panel discussion leader, circulated a detailed email message describing the threats he had been receiving. At the time, we said that Mir’s open, public response to the threats was a textbook case of how to handle the steady stream of intimidation that journalists face–not just in Pakistan, but in other parts of the world as well–and we encouraged others receiving threats to do the same. The next day, we reported that Mir had been given protection by Pakistan’s Interior Ministry and that President Asif Ali Zardari had ordered an investigation into the case.

The tactic seemed to be working. Umar Cheema, a reporter for Islamabad’s The News, and I began encouraging other journalists facing threats to do the same. In 2010, Cheema had set the standard for confronting threats and attacks made on journalists when he went public with the attack made on him by men he is convinced were agents of Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence Directorate.

But I have a concern: Sethi, Mohsin, Mir, and Cheema are prominent journalists. Others with a lower profile who faced similar threats have not gotten the same level of response to their decision to go public. Ghulamuddin, a producer for Samaa TV in Karachi, and his co-producer Mohammad Aatif Khan, came forward to tell the world about the torrent of threats they received as soon as their story on students held in chains at a Karachi seminary had aired. But when we published a story on the matter, “Where is the state?” asks Pakistani journalist under threat, there were only two comments at the bottom of the post, unlike the long string of comments that followed Mir’s story. And, more important, there was very little, if any, official reaction.

I am in talks with two more Pakistani journalists who have told me of being threatened the way Sethi, Mohsin, and Mir were. So far, those two have decided not to come forward. These reporters are lower in profile, peers of Ghulamuddin.

Ghulamuddin’s words portray a different reality for less prominent reporters who dare to speak out:

“Given these highly stressful circumstances, I am living in hiding in Pakistan. My wife and our six-month-old child are with me, all because I produced a story advancing human rights and freedom.

For my colleague Khan and our families, it is a stark reality that the entire state of Pakistan remains a silent spectator as we and others in the journalists’ community face such threats as we go about pursuing our jobs. As it stands now, we are considering the option of seeking asylum outside our country as the only way of avoiding being butchered by the groups pursuing us.”

The headlines about Sethi and Mohsin’s return to Pakistan–“Threats for speaking on military’s role in politics: Sethi,” “Questioned military’s role, Pak journo ‘threatened,’” “Pakistani journalists under threat from military“–are typical. They would almost make you think the threats are coming from the military and security establishment, even though Sethi makes clear they are from a variety of sources. Yes, the ISI and its friends are prime suspects in some of the attacks on journalists, but by no means in all of the cases.

A level of danger pervades the industry, and for the last two years, CPJ has ranked Pakistan as the world’s deadliest country for journalists. The courageous steps of some men and women in recent days to confront that menace head-on is admirable, but their courage alone won’t be enough to reverse the trend. The reality is that governance is weak in Pakistan, and it will require a concerted effort over a long time before Pakistani journalists–and normal citizens, for that matter–can live without fear of retribution.