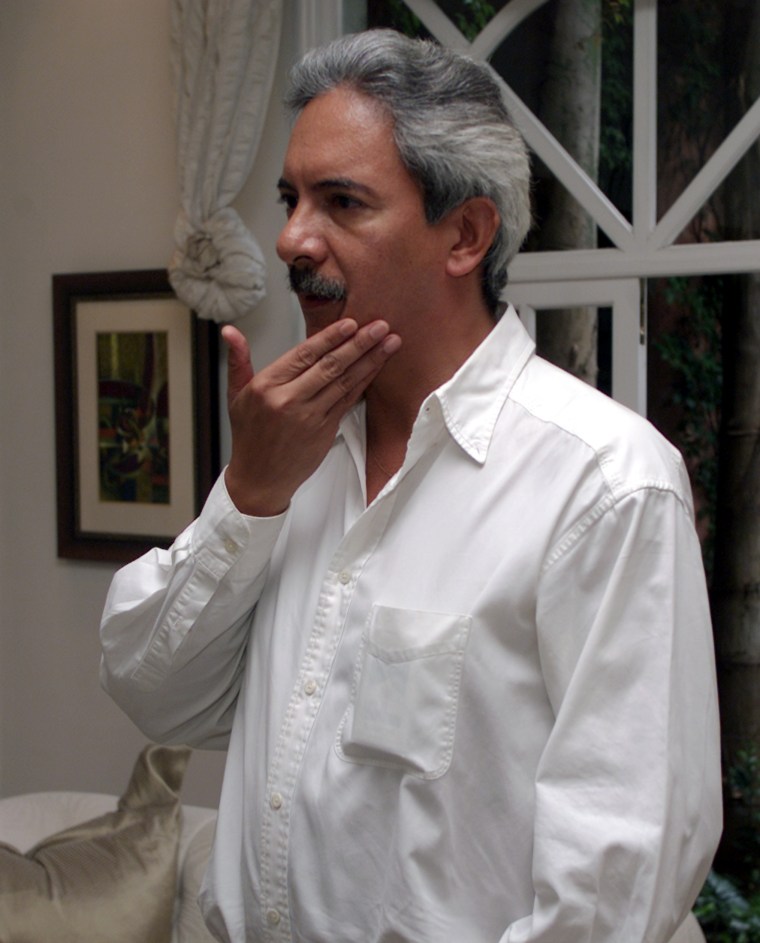

Two days after being abducted and badly beaten in Guatemala, prominent journalist José Rubén Zamora was still in shock. “I can’t remember what happened, but I was drugged and left unconscious in a hospital in the outskirts of Guatemala City,” he told me on Saturday after he was released from the local hospital.

His colleagues at the daily elPeriodico and members of the local media were stunned by the news on Thursday. Rumors had spread that morning that Zamora had been killed. Claudia Mendez, an editor at the paper, told me that she started crying. Zamora, a 1995 recipient of CPJ’s International Press Freedom Award, is considered one of the top investigative journalists in Central America by his peers.

On Wednesday night, Zamora ate dinner at a local restaurant with a couple of friends and then went to a bar for drinks. His friends didn’t like the place, he said, so they left. Zamora paid the check, and that’s the last thing he remembers. His car was found the next morning a few blocks away. His credit cards and cell phone had been stolen. When his family and close colleagues called him that morning, someone answered and said that Zamora had been murdered.

In the early afternoon a call from a local hospital brought great relief: Zamora was alive and recovering. I was visiting the office of Cerigua, a local press group, when someone from the UN called to tell us. Ileana Alamilla, the group’s director, then phoned Juan Luis Front, elPeriodico‘s editor, and he confirmed the good news.

Details of the disturbing incident were published in the press the next morning. After being badly beaten, Zamora was left almost naked and unconscious in the town of Chimaltenango, 25 miles (40 kilometers) away from the capital. Someone called the local firemen, who took him to a nearby hospital. Zamora‘s vital signs were so weak that he was then taken to a hospital in Guatemala City. It was then, while still in state of confusion, that the journalist called his family.

Zamora had been the victim of a vicious attack in 2003, and his colleagues said he has made many enemies as a result of years investigating organized crime and corruption in Guatemala. Zamora said he has no idea if his attack was a result of the climate of violence in the country or an act of intimidation, but that “there are video cameras that have caught one of the attackers, and investigators will probably find out.”

Human rights ombudsman Sergio Morales gave me some chilling statistics: Guatemala has a daily average of 16 killings, with a total of 21,000 over the last three years. Nine out of 10 murders go unpunished, he said.

President Álvaro Colom and other high-ranking officials have expressed their concern about Zamora’s attack, while the prosecutor who investigates crimes against the press has begun an inquiry. In the meantime, Zamora needs police protection. The OAS Inter American Commission on Human Rights ordered protective measures after the 2003 attack, but surprisingly, authorities did not provide Zamora the necessary protection to ensure that he is able to work without fear of reprisal.