Introduction

On January 6, 1999, rebel forces entered Freetown and launched a campaign of terror. Revolutionary United Front (RUF) fighters systematically murdered, mutilated, and raped thousands of civilians. During the three weeks that it took for Nigerian-led West African peacekeeping troops to expel the rebels from Freetown, Sierra Leone officially became the most dangerous country in the world in which to be a journalist.

The RUF saw all journalists as enemies, to be hunted down and killed. Rebel fighters murdered at least eight journalists–some together with family members, all of them brutally. A ninth was killed by soldiers of the Nigerian-led West African peacekeeping force (ECOMOG), and a 10th died in prison after the government denied him medical treatment.

The civil war began in 1991, when the RUF launched its first offensive from neighboring Liberia. Since then the independent press in Sierra Leone has faced harassment, threats, and censorship, often in the name of “national security.” Journalists have been targeted by every party to the increasingly complicated conflict: civilian governments, various military juntas, rebel forces, ECOMOG peacekeepers, even South African mercenaries and traditional Sierra Leonean hunters, or Kamajors, who organized themselves into civilian guards in an effort to defend their villages against the rebels.

Both government and rebels fought to control Sierra Leone’s lucrative diamond trade. In effect, the conflict seems rooted more in commerce than in ideology. In May 1997, I was living in Freetown and working as a free-lance reporter for the BBC and several other Western news organizations. On May 25, renegade soldiers and their RUF rebel allies seized power from the civilian government of President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah. That was Sierra Leone’s third coup in five years, and it ended the country’s brief experiment with democracy. Sierra Leone’s first democratically elected government in nearly three decades had lasted just over a year.

This was the most violent coup to date; it also marked the first time that the war had reached Freetown. All that day, mixed groups of soldiers and civilians shot their way into homes and offices. They wore a motley assortment of army fatigues and civilian clothing. Some sported World War II helmets, gas masks, and even Santa Claus hats. All carried AK47 assault rifles or rocket-propelled grenade launchers. They emerged laden with bed frames and cooking pots, video recorders and satellite dishes, which they loaded onto stolen pickup trucks.

Soldiers returned to my house eight times, growing increasingly drunk and aggressive as the day wore on. The rebels killed an estimated 50 people that first day. Many other people were attacked. Some, including foreigners, were raped.

I left Sierra Leone a week later, evacuated by the U.S. Marines. Most of my Sierra Leonean colleagues were not offered this option; they stayed on and tried to do their jobs under an increasingly unpredictable military junta. Although ECOMOG peacekeeping forces ousted the junta in March 1998, journalists continued to live in a state of fear and self-censorship–not least because human-rights abuses were committed, in differing degrees, by all parties to the conflict.

Even now, since the signing of the LomŽ peace agreement between the government of President Kabbah and the RUF in July 1999, journalists in Freetown continue to suffer threats, harassment, and attacks. Some continue to bear witness, while others have fallen silent out of fear. Some of the threats come from former rebel leaders, who were granted amnesty under the LomŽ agreement. Others come directly from the government or ECOMOG peacekeepers, who are effectively responsible for national security now that the army and police force have disintegrated.

The 1997 coup taught us what the RUF was capable of, but in retrospect it offered only a foretaste of the horrors that took place in January 1999. While everyone in Freetown suffered, journalists were particular targets of rebel rage. Accordingly, the Committee to Protect Journalists asked three Sierra Leonean reporters to write down their personal recollections of the RUF occupation.

The Day the Rebels Came to Town

by Aroun Rashid Deen

My cousin woke me up on Wednesday, January 6, at 1:45 a.m. She said the rebels had entered Freetown from the east. I jumped out of bed along with my wife, who was three months pregnant. She took our two-year-old son from bed also and tied him on her back. We heard firing from the outskirts of town.

I knew the rebels would be looking for me because of a state TV program on rebel atrocities that I produced and hosted between March and August 1998, after West African peacekeeping troops (ECOMOG) threw out a junta composed of rebel leaders and former army officers and reinstated the civilian government of President Kabbah.

Outside we saw many worried-looking people hurrying from the Kissy end of Freetown, which is the gateway to the city. Most were women. Some carried babies on their backs, and others had bundles on their heads. As they moved toward the city center they cried, “The rebels are coming! The rebels have entered the city! The rebels are here!”

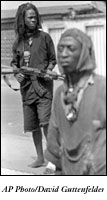

Cocaine plasters

By 7 a.m. there were rebels everywhere. A number of them looked like former Sierra Leone army soldiers, many of whom joined the ranks of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) after March 1998, when ECOMOG kicked out the most recent military junta. Some carried Russian AK-47 or NATO-standard G3 assault rifles, while others toted long, bulbous, rocket-propelled grenade launchers. They were gaunt and hungry-looking, with “cocaine plasters” on their faces.

RUF commanders spent some of their profits from the diamond trade on drugs. They would give their fighters cocaine for military operations, so that they would find it easier to kill and torture. Many of the fighters were adolescent boys. They used razor blades to cut small incisions in their faces and rubbed cocaine powder inside. Then they covered up the incisions with plasters. You would see RUF fighters greeting people perfectly normally when they weren’t drugged. But during operations they would change completely. The drugs had a lot to do with it.

Two women entered our compound, carrying AK-47s and extra ammunition clips. I recognized them from the crowd of civilian women we had just seen fleeing from the advancing rebels. Suddenly I understood the rebel strategy. They had sent female rebels ahead dressed in civilian clothes, carrying arms and ammunition wrapped in bundles on their heads. The idea was to spread panic among the people of Freetown so that they would pour out into the street, creating a human shield between the ECOMOG troops and the rebels. It worked: the ECOMOG soldiers were reluctant to fire into a crowd of civilians, and that made it much easier for the rebels to enter Freetown.

Ten minutes later I heard an explosion, followed by the sound of people wailing. I followed a crowd of people over to a nearby flat and stood in the back so that the rebels would not be able to single me out. The remains of eight people lay scattered around the living room. They were all from the same family. The heads of two 10-year-old children, a boy and a girl, had been severed from their bodies. The only survivor was a badly injured four-year-old girl.

Her father had been outside when the grenade went off. He stood over his dead family, weeping bitterly. Then a boy walked into the compound, holding a grenade launcher. He was about 14 or 15 years old, with short-cropped hair, wearing jeans but no shirt. His face was covered in plasters. Shouting in broken Krio, he told the people who were crying to shut up. Some did. He said that he had fired the grenade and would do the same again, if necessary.

He bent over a dead woman, scooped up some of her blood, and rubbed it all over his face. Then he left.

Hunted

I walked back to my own house and hid in a shed that had a window, through which I could see most of the compound without being seen. About half an hour later, two small boys came into our compound. I recognized them and called the older one by name. He turned at the sound of my voice but could not see me. I left my hiding place and waved them over. The younger one suggested I leave immediately, because the rebels were moving from house to house, asking about my whereabouts and announcing that they had vowed to capture me dead or alive. Then they left.

My family and I spent the next four weeks hiding in a cellar underneath the house of one of my close friends, who worked as a finance clerk in one of the government departments and lived about 200 meters from the seaport. There was no electricity or telephone service in Freetown during the rebel occupation. We couldn’t even light a fire, because we were afraid that the rebels might see it, so we lived on cassava flour mixed with water.

Apart from the BBC, our only source of news was FM 98.1, a radio station located in ECOMOG-controlled territory in the far west of Freetown. The rebels suspected everybody of passing information about them to 98.1. Once, I was told, they saw a man listening to his transistor radio near our hideout. The radio looked a lot like a cell phone, so the rebels accused him of spying for 98.1. He tried to explain, but they wouldn’t listen. They just shot him and then burned his house down.

Life in Freetown

It was often noisy at night. Because of the blackout and the danger outside, people were going to bed early. But the rebels wanted everybody to stay up late. They made bonfires of tires and fallen trees and sang songs in praise of the RUF, similar to the songs we Sierra Leoneans like to sing at football matches and weddings. At night they would move from house to house, forcing young men and women to come outside. The rebels wanted civilians around them at all times, so that ECOMOG troops and fighter planes wouldn’t be able to single them out. Despite their desire to kill and maim, the RUF fighters couldn’t stand fighter jets: they would run and hide whenever they came overhead.

One night I heard the sound of an approaching car. It was a Peugeot 504 sedan, which we call a “familiar” car. It stopped about 200 meters from my hiding place, and six armed rebels got out. The driver then reversed and drove back to the main highway.

The rebels entered a construction site and started shooting in the air. I heard people screaming and weeping in the distance. After about two minutes of shooting they came out of the unfinished house and started banging on house doors. Nobody came out at first, but then the rebels shouted that they would kill anybody who stayed inside.

The first people to emerge were two men, who came out holding their hands above their heads. The rebels kept shouting, and in less than five minutes more than 40 people came out in the street. The rebels ordered them to sit on the ground with their hands on their heads.

One of the rebels was addressing them. I couldn’t make out what he was saying. Suddenly I heard several guns being cocked simultaneously. But before the massacre could begin, a woman stood up and pleaded for mercy. She moved close to the rebel who was speaking. One of his colleagues rushed up and hit her with his gun, but she continued pleading. Then she shrieked as the speaker grabbed her protruding breast. He then ordered her to sit down, but in a gentle voice.

The rebels ordered all the women to follow them. They told the men to keep watch and report what they called “strange moves or attempts by the enemy.” Then the rebels left. About 13 women followed their captors out of sight.

Aroun Rashid Deen survived the RUF invasion and went back to work for the state television network. A few months later he got an anonymous telephone call from a man who said, “We’re back,” and then hung up. With the help of an emergency grant from the Committee to Protect Journalists, he was able to leave Freetown on July 31. He arrived in New York on August 1 and began seeking political asylum in the United States. His family remained in Freetown.

Freetown Diary

by Mike Butscher

January 6

When the shooting started at 3 a.m., I was sound asleep in my guesthouse on Rawdon Street. My Nigerian colleague Martin I. Martins walked into my room and woke me up. “The bastards have arrived!” he said. I got out of bed, and we stood at my third-floor window.

On the street below, we saw hundreds of people surging toward the west end of Freetown. Vehicles were jammed nose to tail, moving at a snail’s pace. It was obvious that the rebels had penetrated what we thought was ECOMOG’s impregnable wall around the capital. Martin and I sat down on my bed and remained silent for about three minutes, until another explosion rocked the guest house.

Pios Foray, editor of the Democrat newspaper, walked into my room with four female tenants. I told Pios and the women that I couldn’t go anywhere because I had no money. Pios and Martin had some cash, so we decided to stay there and live like a family. Six tenants were now sleeping in my room.

January 7

We got sleep all night long. Hundreds of people flooded into the west end of Freetown, fleeing the rebels who were approaching from the east. The women in our guest house were terribly frightened. The rebels reached Rawdon Street at 3 a.m. We heard shouted abuses, screams, victory chants, grenade explosions, and sustained gunfire. At 7 a.m. they burned Sonny Marke, Freetown’s most popular bar. It was the end of an era.

Meanwhile, the Pademba Road prison was flung open. The prisoners included rebels, former soldiers, and criminals. They were all unleashed on us. In the morning a rocket-propelled grenade exploded in the room next door. I moved to Pios’ room on the second floor. There was no bunker–whenever the shooting started, we all lay on the floor.

The BBC, Radio France International, and VOA were now my only sources of news about what was happening in my country. The Sierra Leone Broadcasting Service was completely useless. Peeping through a curtain at 8:30 a.m., I saw three bound Nigerian traders hurled onto the street from a car with no doors. Rebels then took turns cutting their throats.

All the cars on Rawdon Street were burning. There were clouds of smoke all over Freetown and heavy looting on Ecowas, Goderich, Kissy, and Wilberforce streets. On the radio, Information Minister Dr. Julius Spencer kept telling everyone to stay indoors. Anyone found on the street would be shot. Meanwhile, eastern and central Freetown were now fully controlled by the rebels, who were carrying out mass amputations. All telephone lines were down, and there was no electricity. There was heavy bombardment by ECOMOG, who promised to liberate us. Time was running out.

January 8

A gloomy morning. President Kabbah called for a cease-fire, but Maskita [“Mosquito,” the nom de guerre of RUF commander Sam Bockarie] vowed to fight on. Rebel headquarters were now located on Rawdon Street, near my guest house. Rebels tried unsuccessfully to climb our gate this morning. As journalists we were all in danger, but Martin was particularly vulnerable because of his Nigerian nationality. It was time to leave. Martin and I slipped out of the guest house wearing shorts and slippers, with white cloths around our heads to make us look like RUF supporters.

The rebels were everywhere, but we chose a route through the quieter back streets. The city center was destroyed and littered with corpses. At the entrance to Connaught Hospital, a rotting pile of bodies emitted an offensive smell. We held our noses as we quickly walked through Kroo Bay, Kingtom, and Ascension Town. Finally we reached Congo Town, which is ECOMOG territory. Holding our hands in the air, we walked over to some ECOMOG and Sierra Leone army soldiers.

Martin had money, so we retired to a shop where we each guzzled two pints of very cold beer, our first in three days. Then we paid a soldier to drive us to the headquarters of the ECOMOG 7th Battalion, at Goderich. The soldier dropped us at Lumley, and we walked the rest of the way, passing several ambushes laid by Nigerian soldiers along the Peninsular Road.

But when we reached ECOMOG headquarters, the Nigerian colonel ordered his men to kick me out of the camp. He accepted Martin, but he wouldn’t trust a Sierra Leonean. I felt angry at being rejected by strangers in my own country, but how could I blame him? Luckily the adjutant agreed to smuggle me into his billet for the night, because it was dark and we were exhausted.

January 9

Spent the morning with a more reasonable ECOMOG major. We talked while I listened to ECOMOG air and ground operations over his handset. ECOMOG had advanced beyond Congo Cross and was now engaging the rebels at Kingtom. They dubbed their assault “Operation Search and Destroy.”

I slept at my sister’s house near the front line. What if I died now? I wouldn’t be able to see my newborn child. Information Minister Spencer came back on the radio, telling the nation that ECOMOG was advancing. The rebels were pushed out of the town center, and ECOMOG jets were patrolling the sky over Freetown. I felt it was safe to go back and check my room on Rawdon Street. I wanted to get home, collect my belongings, and leave the capital.

January 10

Five key rebel commanders were killed on a suicide mission–ECOMOG troops shot them to pieces as they tried to drive across the Congo Cross front line in a Pajero jeep. Martin and I tried to cross the line in the opposite direction, but Nigerian soldiers turned us back at the National Stadium junction. Then shots started flying, and we ran for cover.

We found shelter nearby at the house of Dr. Olu Williams, who welcomed us warmly. We spent the night there, and he didn’t charge us for food or lodging. There were more amputations in the RUF-controlled east end of Freetown.

January 11, 7:30 a.m.

The rebels retreated. There was gunfire everywhere. ECOMOG reinforcements headed for Kingtom, where part of the city’s power generation plant was damaged. Nearly 100 people have been killed there, mostly police. On 98.1 FM, rebel spokesman Allieu Kamara asked for forgiveness while Freetown burned. When Martin and I left Dr. Williams’ place, we saw the burnt-out vehicle that the five rebel commanders were riding in when ECOMOG soldiers killed them yesterday.

The area smelled of explosives and human blood. The sky was dark, and a blanket of smoke hung over the city. We crossed a bridge that had been a battleground 24 hours earlier, walking on spent shells with every step. We saw innumerable bodies under the bridge and vultures hovering overhead. My legs felt shaky, but I tried to be a man as we passed bullet-riddled bodies and vehicles. One corpse had been hit in the head; his brains were spilled all over the tarmac.

Martin urged me on through the deserted streets. Soldiers grinned nastily as we passed the ECOMOG checkpoints. They wouldn’t let us go beyond Cotton Tree, even though Martin spoke to them in Hausa, a language commonly spoken in Nigeria. We took cover from the firing in Bathurst Street. I saw some residents peeping out of their houses, but they ignored my pleas to be let in. They must have thought I was a rebel. We stayed there for about an hour, until the firing died down. We slept outside at Percy Street–there were bonfires everywhere.

January 12

We tried again to cross Cotton Tree to reach our guest house, which was only five minutes away. And again ECOMOG soldiers turned us back, saying that the area was unsafe. We toured central Freetown during a brief lull in the firing. Bathurst, Percival, Liverpool, and Soldier streets were ravaged by fire. I counted 30 houses razed on Bathurst street alone.

A man offered the rebels 100,000 leones (about US$33 at the time) not to take his teenage daughter away. They took his money, tied him up, laid him down in the street, and pumped mosquito spray into his mouth. Then they took his daughter. I spent the night with my colleague Jon Foray, who had a room at the Stadium Hotel.

January 13

Martin found me at the stadium. An ECOMOG soldier who had been trapped under a culvert for four days with no food emerged today. ECOMOG launched Operation Death Before Dishonor.

January 14

The government has ordered the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to leave Freetown. President Charles Taylor of Liberia just declared a cease-fire for Sierra Leone.

January 15

RUF commander Sam Bockarie called President Taylor’s bluff. “Oh, chief, let the cease-fire be on Monday or Tuesday,” he told the BBC sarcastically. So who did Taylor think he was fooling? Meanwhile, I watched three big trucks dump bodies at the Ascension Town cemetery. Five dogs hauled a rebel’s body from his grave, growling over their catch. I wished I’d had my camera.

January 16

President Kabbah dismissed Taylor’s cease-fire call today and announced that [rebel leader Foday] Sankoh would remain in prison. The United States denounced the Taylor government for meddling in Sierra Leonean affairs. Meanwhile, Martin and I parted company. More than 500 displaced people from the east end arrived at the stadium, and more were on the way.

January 17

I attended a church service at the stadium. The dogs launched their own rebellion; I saw more of them at the cemetery today, howling and competing over human flesh. Meanwhile, ECOMOG pushed the rebels all the way back to the east end of Freetown. There were checkpoints at every street junction. I dashed home to my sister’s house at Congo Cross, just in time for the 3 p.m. – 9 a.m. curfew. There had been no public or private transport service in Freetown since January 6.

January 18

After trying unsuccessfully for several days, I finally made it past the ECOMOG checkpoint to pick up my luggage at the guest house. An ECOMOG soldier stopped me at the corner of Siaka and Rawdon streets: “You’re playing with your life, eh! Identify yourself and where you’re going!” I passed the test and hurried to the guest house, just a few steps away. I banged the gate several times before the caretaker opened it. “We’ve been worried about you, thank God for life,” he said, embracing me.

I headed for Cockerill to try and get a ride out on an ECOMOG helicopter. But the ECOMOG captain turned me down. Somehow my colleague Roy Stevens got me a spot on the chopper. I was shaking all the way to the airport at Lungi. The airport was mobbed with families, Westerners, and Lebanese, all desperate to leave Sierra Leone. Captain Asgill of the Inter Tropic airline agreed to take me to Conakry [in Guinea] and let me pay later. I was the last person to get my passport stamped. When I entered the plane I was drenched in sweat. It took some time before I recovered. In Conakry, BBC correspondent Alhassan Sillah paid for my room in the Hanoi Hotel, where I spent a sleepless night. I’m broke, but I still have faith.

Mike Butscher is currently finishing the research for a proposed book on Sierra Leone, entitled Confidence Betrayed. The book aims to be a comprehensive historical analysis of the origins of rebel activities in Sierra Leone: how the political situation deteriorated into anarchy when soldiers of the regular army joined forces with the rebel Revolutionary United Front (RUF) to oust a legitimate government; a depiction of the terrible trauma suffered by the civilian population, and how a tentative peace was finally achieved.

The Trauma of Sierra Leone

by Claudia A.R. Anthony

For me, the rebel invasion of Freetown began in mid-December 1998, when I heard persistent sounds of heavy artillery shelling in the Sumbuya area, around 40 kilometers east of the capital.

I was living in the village of Waterloo, about 20 kilometers east of Freetown. Four days later, I was slumped on my veranda drafting a news item for my paper, The Tribune of the People, when thousands of people of all ages, carrying their bundled belongings on their heads, streamed by. I put down my writing tools and rushed over to speak to refugees. They said that armed rebels entered their village about midnight and went on a spree of looting, destroying houses, killing people, raping girls and women, and abducting children. “They all vanished by morning,” an elderly man informed me.

Two days later at about 2 a.m., the rebels struck Waterloo, leaving behind over 70 burnt houses. They abducted an estimated 120 young men, women, and children, carried away millions of leones in food, property, and cash, and killed five people. I had just finished my bath and was washing my clothes when intense small-arms fire broke out about 30 meters away. Then I saw my 45-year-old cousin Willard in the window. He screamed at me to flee.

“How can I leave Cess?” I asked, referring to my daughter.

“Don’t say I didn’t warn you!” he shouted as he ran off.

Cess was with my mother, who had taken her along on a village tour to see the destruction left behind by the rebels. I decided to hide in the lavatory and wait for their return.

They finally arrived, panting for breath. “Where’s Willard?” asked my mother.

“He’s gone. Let’s go!” I said. I took my daughter’s hand and urged my 60-year-old mother to hurry. Nearly every minute, my mother complained that she was tired and could go no farther. We took off our slippers and waded through the swamp. As we approached the tarmac at Devil Hole, about four kilometers away from home, I realized that I was wearing only a torn bath towel.

That afternoon, Dominic Kabba Kargbo, my colleague and village-mate, received a thorough beating from a mob in Freetown after the afternoon edition of the BBC’s “Focus on Africa” was aired. Kargbo’s crime was telling BBC anchor Robin White how rebels had descended on the moonlit village and devoured it.

My family and I attempted to resettle in the village, but a third attack on Wednesday the 30th sent us packing with a crowd of refugees. I carried two bags on my shoulders, and I had to stop every five kilometers so that my exhausted mother could rest.

We eventually arrived at my cousin’s tiny one-room apartment, about 10 meters away from the maximum-security prison west of Freetown. When the rebels entered Freetown on January 6, they opened the prison doors. Freed inmates ran into the streets in the hundreds.

We didn’t dare venture outside. We ate leftovers. There was no sugar for a cup of tea. From the window I could see armed men and boys in military fatigues shouting that we had nothing to fear. Sporadic shelling continued. Telephone messages from family and friends spoke of summary killings, indiscriminate looting, and intimidation in the central and eastern districts. After a stray bullet killed my niece, her frightened family abandoned her corpse and fled to shelter in a nearby mosque. A repeated radio statement warned us to stay indoors and assured us that the Nigerian-led West African peacekeeping force (ECOMOG) was “in full control of the situation.”

The next day, the rebels ordered everyone in the neighborhood to stand outside and chant, “We want peace!” I hid behind an elderly man. All of us clapped and sang like schoolchildren. As three teenage soldiers approached, the clapping and singing became louder and the pitch of the chorus rose. A nauseating fear gripped my stomach, for I might be identified as a jour- nalist. But they only demanded cash and assured us that peace was here to stay.

Claudia Anthony is an experienced print journalist and has a special interest in child rights. She is also an active advocate for the rights of the relatively few female journalists in Sierra Leone. In November 1999 she launched the Alliance for Female Journalists in Sierra Leone.