Posted: May 6, 2005

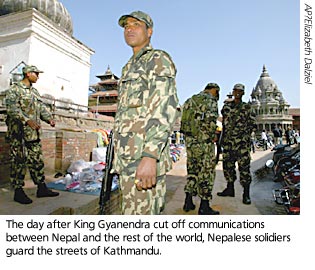

At 10:25 a.m. on February 1, King Gyanendra of Nepal delivered a stunning proclamation– Nepal’s multi-party government had been dismissed and a state of emergency declared. Simultaneously, telephone lines across the country were cut, mobile phone service discontinued, and fax and Internet connections shut down. Backed by the Royal Nepalese Army, the king seized state television and radio, placed the country’s political leaders under house arrest, and silenced the press with military occupations of major media houses and wide bans on reporting.

In the silence that followed, a surprising thing happened.

The king was unable to shut off Nepal from the rest of the world. Rather, in the days after the coup, smuggled e-mails, clandestine Web sites, and the unlikely emergence of a handful of Nepalese bloggers threw the government and independent journalists into a cat-and-mouse chase. The king’s unintentional result: While attempting to plunge Nepal into a communications dark age, he spawned a small legion of online journalists.

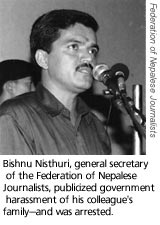

Shortly after the announcement, Tara Nath Dahal, president of the Federation of Nepalese Journalists (FNJ) emerged from his home to find the streets deserted. When he arrived at the umbrella organization’s building, “no journalists had come to the office for fear of arrest,” he said in a CPJ interview. Resolved to take a stand against the king’s curtailment of Nepal’s hard-won press freedom, Dahal met with FNJ General Secretary Bishnu Nisthuri and decided to risk arrest by writing a statement that would condemn the king’s actions and boost the morale of his colleagues.

“The royal announcement made yesterday, by ending the spirit and value of the constitution of Nepal, is a coup against democracy and peoples’ rights,” the explosive first sentence read. The following morning, Dahal met with other central committee members of the FNJ and secretly printed out the statement.

“The royal announcement made yesterday, by ending the spirit and value of the constitution of Nepal, is a coup against democracy and peoples’ rights,” the explosive first sentence read. The following morning, Dahal met with other central committee members of the FNJ and secretly printed out the statement.

Now came the hard part–distribution. Without telephone, fax, e-mail, or Internet, the statement was delivered to international non governmental organizations, diplomatic offices, media houses, and foreign journalists by bicycle and motorcycle couriers. Within hours, it had been photocopied countless times. Soon, it was translated into English, and, via satellite connections accessible to diplomats and foreign journalists, an electronic version appeared in in-boxes across the world.

Dahal went into hiding. When security forces surrounded his house and harassed his family, Nisthuri wrote and distributed a statement calling attention to the treatment of the FNJ president. On February 4, it was Nisthuri who was arrested.

In those initial days, the coup seemed to generate little national protest. Racked by a civil conflict between Maoist rebels and the government, Nepal had been run down by violence. Faith in political parties had been compromised by corruption. Some Nepalese believed that the king’s drastic actions were in order; many feared that dissent would mean arrest. And in a poor country where only about 80,000 of 27 million citizens are regular Internet users, where illiteracy is high and phone lines don’t reach large swaths of the mountains, a communications blackout isn’t a lifechanging event for many people.

Dinesh Wagle, an arts reporter for Nepal’s major daily Kantipur and a pioneering Nepalese blogger, was entirely absent from the blogosphere during the first week of the coup. The Internet remained down until February 8, and he lacked access to expensive satellite connections. Regardless, his United We Blog! (UWB, www.blog. com.np), had rarely dealt with politics. The site was primarily an English language diary with threads on music, parties, and the media.

But when Internet communication resumed, Kantipur and all other media outlets were still barred from any reporting “that goes against the letter and the spirit of the royal proclamation.” So, while the king’s army dismantled community radio and choked dissent in the country’s Nepali-language publications, the Web site posted its new motto: “United We Blog! wants Peace and Democracy [to] be restored in Nepal as soon as possible.”

Wagle’s colleagues began to see the blog in a new light, he said. “Even those folks at Kantipur who didn’t read my blogs or simply ignored them are now following daily,” he wrote in an e-mail to CPJ. “Political reporters also share info with me that they can’t write in Kantipur.” The site provided extensive, street-level coverage of political protests and reports on the arrests of colleagues. Interest soared, both inside and outside of Nepal.

Wagle’s colleagues began to see the blog in a new light, he said. “Even those folks at Kantipur who didn’t read my blogs or simply ignored them are now following daily,” he wrote in an e-mail to CPJ. “Political reporters also share info with me that they can’t write in Kantipur.” The site provided extensive, street-level coverage of political protests and reports on the arrests of colleagues. Interest soared, both inside and outside of Nepal.

The king restored communications with a caveat: security forces could monitor and block media outlets as they saw fit. Were online journalists putting themselves at risk? Wagle admitted that there were submissions he would not post–for example, statements calling for an end to the monarchy. Radio Free Nepal, another blog that emerged after the coup, posted comments anonymously in order to protect contributors.

By April, these two blogs had escaped direct government censorship, but other news Web sites such as the Nepali Post, a Washington, D.C.-based Nepali-language online magazine, had been targeted. Editor Girish Pokhrel said that the government blocked the Web site in Nepal shortly after the resumption of Internet service.

Despite its resolve, the Nepalese government may not have the resources for sophisticated Internet surveillance and blocking. Pokhrel found that readers in Nepal soon accessed the site through overseas proxy servers, which retrieve Web site contents on the user’s behalf. When those proxy servers were blocked, readers found new ones.

Newslook, a U.S.-based English-language Web site that culls international headlines, saw its readership in Nepal multiply by five during the month of February. Editor Dharma Adhikari, a Nepal-born journalism professor at Georgia Southern University, told CPJ that the number of hits from Nepal dropped by only 10 percent when the government blocked the site around February 23. Somehow users were finding a way to get through.

For the most part, Nepalese authorities showed greater tolerance for critical commentary in online news sources than in print publications, and allowed more freedom in English-language media than in Nepalilanguage media. In a country where the Internet is prohibitively expensive and most people do not speak English, the government may not have viewed most online journalism as a threat. Internet journalists, in general, were not in a position to report on the political conflict that raged in the country’s rural areas. On the other hand, the king’s post-coup directives struck at the heart of community radio, a primary source of information for the many Nepalese who are illiterate. Independent newscasts were banned, and reports on the Maoist insurgency were restricted.

As Nepalese began to report electronically to the world, however, the world responded. The international outcry over the imprisonment of Nisthuri helped to win his release on February 25. Though under pressure from the government, Dahal evaded arrest and teamed with other advocates to launch the Web site Press Freedom Nepal (www.pressfreedomnepal.org), which posts press freedom violations and relevant news. The fight for the Internet is not over, but Newslook editor Adhikari pointed out the greatest hope for budding online journalists.

“Censoring the ‘Net is not that easy,” he observed. Even for an absolute monarch.

Kristin Jones is research associate for CPJ’s Aisa program.