Dangerous Assignments

There was a time, not long ago, when Indonesian writer and editor Goenawan Mohamad was devoting much of his time to poetry, literature and quiet political organizing. His days of high-pressure journalism and tight weekly deadlines ended when the government banned his highly regarded weekly magazine, Tempo, in 1994 and left him to other pursuits.

He became a symbol of resistance to the regime and found himself at the center of a community of journalists, activists, artists and students bound together by what often seemed a quixotic struggle against the seemingly unassailable leadership of President Suharto. Tempo, which Mohamad, 57, founded in 1971 and built into a profitable, widely respected 200,000 circulation news weekly–Indonesia’s version of Time Magazine–was becoming a distant memory. There seemed little chance that Suharto would ever allow it to publish again.

He became a symbol of resistance to the regime and found himself at the center of a community of journalists, activists, artists and students bound together by what often seemed a quixotic struggle against the seemingly unassailable leadership of President Suharto. Tempo, which Mohamad, 57, founded in 1971 and built into a profitable, widely respected 200,000 circulation news weekly–Indonesia’s version of Time Magazine–was becoming a distant memory. There seemed little chance that Suharto would ever allow it to publish again.

Then came Indonesia’s abrupt economic collapse, widespread rioting and Suharto’s May 21 resignation; what had been one of Southeast Asia’s most prosperous nations appeared headed for chaos. Military rule seemed likely or, worse, civil disintegration under Suharto’s hand-picked successor, Bacharudin Jusuf (B.J.) Habibie, a technocrat and long-time Suharto loyalist.

For Goenawan Mohamad who is a recipient of a 1998 International Press Freedom Award from the Commitee to Protect Journalists–and many of Indonesia’s journalists, however, a funny thing happened on the way to calamity. They are back in the magazine business. For all of its dire troubles, Indonesia suddenly has one of the freest presses in Asia and the Habibie government has put few, if any, restrictions on publications.

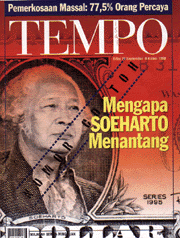

This new found freedom seems all the more real with the relaunch of Tempo in October. Back from publiishing purgatory, Tempo‘s relaunch party on October 4 was a full-blown social event in Jakarta, drawing some 2000 journalists, politicians, government ministers and diplomats to the celebration. The innaugural issue wasted little time attempting to carve out a niche for serious reporting with a cover story titled: “Rape: Fact and Fiction” that delved into the controversy surrounding the rapes of Chinese women during the May rioting.

Mohamad’s quiet days are now officially over. He is back as editorial chief and most of his staff have returned to the magazine after a four-year diaspora. Expectations for the new magazine are high. The new Tempo must recreate a magazine that is a distant memory for its former readers even as it remains an important symbol of the new openness. It will face an economic climate that has seen advertising revenues shrink precipitously and the cost of newsprint soar. It will also face plenty of competition from new publications eager and able to investigate the sins of the past regime and the shortcomings of the current one.

“The odds are that Indonesia will remain in a chaotic situation for some time to come. Violence will be a constant threat and we will become the sick man of Asia. That frightens me and saddens me.” said Mohamad as he reflected on the mission of Tempo shortly before the relaunch. “The most likely thing the press could contribute is to develop a culture of transparency and accountability in the the government. Tempo will hopefully become a place that will defend and expand our freedoms.”

When Tempo was banned in 1994, the proximate cause was a story about an internal government split over the purchase of 39 former East German warships placed by Habibie, who at the time was Research and Technology Minister. Suharto was reportedly furious that the magazine had dared to air a cabinet controversy in public and the Ministry of Information moved quickly to revoke the magazine’s license.

Ironically, though, with Habibie in charge, the government told Mohamad and others early on that there would be no problem reopening the magazine. Within ten days of taking power, Habibie’s Information Minister, Lt. Gen. Mohamad Yunus was assuring the press that the days of strict limitations were over. “We saw him and he told us, you can reopen anytime,” says Fikri Jufri, the former and current Managing Editor of Tempo. “I was shocked.”

Yunus has confounded skeptics in the press with his attitudes. A former special forces commander who was responsible for security in disputed East Timor when five foreign television journalists were killed there during the Indonesian invasion in 1975, he is now a born again believer in a free press. By September he had signed some 180 new publication licenses and he is pushing for the removal of all restrictions on the press. “I want to see more publications in Indonesia,” he said during an interview in his office. “I really do believe that such a thing will provide more information and it will build the creativity of the people.”

Regardless of the government’s attitude, the decision to relaunch Tempo was a difficult one for Mohamad and others involved. The loose network of former Tempo employees and others affiliated with the independent press movement in Indonesia were consulted, long meetings were held. Some argued that Tempo should remain a part of history and that new publications should take its place. Others insisted that the Tempo name was too important to allow it to die. And already Detak, a fiery tabloid banned at the same time as Tempo, had reopened; it seemed that Tempo had a duty to publish.

Regardless of the government’s attitude, the decision to relaunch Tempo was a difficult one for Mohamad and others involved. The loose network of former Tempo employees and others affiliated with the independent press movement in Indonesia were consulted, long meetings were held. Some argued that Tempo should remain a part of history and that new publications should take its place. Others insisted that the Tempo name was too important to allow it to die. And already Detak, a fiery tabloid banned at the same time as Tempo, had reopened; it seemed that Tempo had a duty to publish.

Complicating matters further, many former Tempo editors and reporters had settled in at other publications or changed careers. To reopen the magazine would inevitably cause some dislocation, especially to those involved with D&R, a magazine owned by the Tempo group which had switched from detective and romance stories to a political format after the Tempo banning. In the last year, D&R came into its own under editor Bambang Bujono, another Tempo veteran, by challenging the Suharto regime with critical coverage and being threatened with closure in March for a controversial cover that depicted Suharto as a King of Spades playing card.

But in order to make way for Tempo and to avoid any potential conflict of interest in the group, D&R was sold to the Jakarta Post newspaper group. Half of its thirty reporters are moving to Tempo, with the blessing of editor Bujono, who nonetheless seemed wistful as he contemplated the loss of his staff. “This is a publication that sides with the people, that is for the people,” he said of D&R. “I am staying because I want to keep this magazine going.”

The controversy and the dislocation aside, given what Tempo means for Indonesian journalism, there is little Goenawan Mohamad could have done but reopen. With Tempo back on the stands, there is a sense of normalcy to the remarkable journalistic rebirth in Jakarta. The challenge for Mohamad and his staff will be to produce a magazine that reflects this difficult and exciting time in Indonesia.

It is a challenge Mohamad is keenly aware of. “After Suharto left, there was an eagerness to bring it back on the part of many journalists but others said Tempo was something of a legend, and that it should stay that way,” Mohamad says. “This makes our task difficult. It is not easy to create a legend every week.”