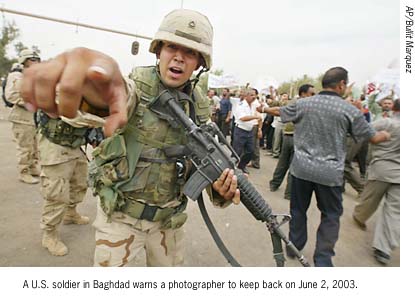

Iraqi journalists frequently face hazardous conditions on the job.

By Joel Campagna and Hani Sabra

These statistics demonstrate the growing role that Iraqi journalists are playing in Iraq and the growing dangers they face as a result. Hundreds of Iraqi journalists are working for the newly emergent independent media, which ranges from coalition-backed newspapers and broadcasters to broadsheets allied with political and religious groups. Many others are working as reporters, fixers, and translators for international media outlets. During uprisings in Fallujah and Najaf in April, these journalists played a critical role in reporting from places that were too dangerous for Western journalists, particularly those from the United States, the United Kingdom, and other countries participating in the coalition.

“Western journalists are not wanted at the present time in Iraq, especially in areas where there is resistance,” said a Fallujah-based Iraqi journalist who works for an international news outlet who agreed to be identified as Mohammed, not his real name. “The people, the resistance, and the mujahedeen [suspect] that these foreign journalists could possibly be spies.”

In early April, when at least six members of the press were among the several dozen foreigners abducted by armed Iraqi groups, travel beyond Baghdad became exceedingly dangerous for foreign media. “Westerners don’t want to go anywhere near Fallujah or Najaf, which are the two hot spots right now,” noted Sam Dagher, a Lebanese-American reporter with Agence France-Presse (AFP), in April at the height of the kidnappings. For several weeks, many correspondents stayed put in their hotels in the capital or traveled only as embeds with coalition troops.

Local Iraqi journalists, however, continued their work as stringers and fixers for international news organizations, providing critical logistical support in navigating hostile terrain and gathering raw data, including dispatches and photos. Using Iraqi journalists, pan-Arab media outlets such as Al-Jazeera and Al-Arabiyya have been able to broadcast exclusive news stories, such as the aftermath of attacks on coalition forces, bombings and other explosions, and clashes between U.S. forces and insurgents. In April, a number of Iraqi journalists working for local and international news organizations covered the U.S. military’s siege of Fallujah, albeit with great difficulty, and, as a result, Arab news organizations were the only non-embedded broadcasters reporting live from inside the city.

Even in Baghdad, Iraqi fixers are regularly used to gather basic information. “Our reporters’ movements within the city have been restricted in the last few weeks,” notes Los Angeles Times Deputy Foreign Editor Mary Braswell. “We might drive to different parts of Baghdad, but we are likely to remain in our cars. At times, we’ve had to send our translators out with a list of interview questions.”

Saleh Negm, news director of the pan-Arab satellite channel Al-Arabiyya, which has many Iraqi journalists working on its Baghdad team, says, “If you are Iraqi, you can move around Baghdad more freely. When you have something happening on the ground, a bombing for example, you’ll find, more or less, Iraqi and Arab journalists are covering them.”

But while Iraqis may be able to cover the news in greater safety than foreigners, Iraqis still face severe threats and serious consequences. “On several occasions, our journalists were beaten, threatened by mobs, or fired at with weapons when there was an explosion,” says Al-Arabiyya’s Negm, who explains that crowds can turn on the media in a matter of seconds in an attempt to assign responsibility for the violence.

But Iraqi journalists working for international media outlets don’t have to be at news sites to encounter danger. In early March, armed assailants gunned down Selwan Abdel Ghani Medhi al-Niemi, an Iraqi translator working for the U.S. governmentfunded Voice of America, while he was in his car outside his sister’s home in Baghdad. The gunmen also killed al-Niemi’s 60-year-old mother and 4-year-old daughter, who were in the front seat.

Abdel Ghani’s wife, Ban Adil Serhan, a 28-year-old English literature graduate and a former translator for the U.S.-based media company Knight-Ridder, believes that the gunmen intended to kill her as well. “They thought [Selwan’s] mother in the front seat was me,” she says. “It was at midnight and was dark. She was wearing a scarf like me.” The day of Selwan’s funeral, Ban’s brother discovered a handwritten note outside the family’s front door citing Quranic verses that state people who work with “infidels” should be killed and warning that Ban’s “turn will come soon, God willing.”

Several days later, on March 24, Omar Hashim Kamel, a translator working for Time magazine, was fatally shot while en route to an assignment from Time‘s Baghdad bureau. Other Iraqi staffers working for U.S. news organizations have received anonymous death threats, including one employee of a U.S. daily who was accused of working with the Pentagon-backed Iraqi National Congress (INC) after he had attended an INC press conference.

Suspicion of the media runs high, and gunmen and political factions have detained and threatened several reporters. The Fallujah-based journalist Mohammed says that when he goes to film events, “the mujahedeen have doubts that my motives are not to show the true picture, but to reveal who the mujahedeen are.” He recounts an incident in which an Arab TV journalist angered local insurgents when he filmed gunmen whose faces were not covered by headscarves.

In April, masked men detained Iraqi journalist Mohammed in Fallujah and accused him of working for U.S.-backed media. “I said, ‘Why are you detaining me? … And they said, ‘Because you are with [the U.S. governmentfunded] Alhurra TV station.’ … They said that it was because they had been told that there was a journalist with a microphone with Alhurra written on it. They eventually let me go, but sure enough, they detained the correspondent/cameraman working for Alhurra in Fallujah, and he told them, ‘I am Iraqi, I am of you, with you. Why do you detain me?’ They broke his camera and said, ‘As long as you so much as work with the Americans, we reject your presence here.’ They detained him for five hours before releasing him.”

As a result of these threats and attacks, a number of Iraqi staffers–mainly those working with U.S. and Western news organizations–have quit their work or take great precautions to not be seen or identified with their employers. A few have even fled the country. Recently, an Iraqi translator working for ABC News who, like many other local journalists working for Western news organizations hides the identity of his employer, abruptly quit after he identified himself in public as working for a U.S. news organization at a press conference. “He really feels that he is a target. All these guys (Iraqi interpreters) are incredibly nervous,” said ABC News correspondent David Wright in a recent article in USA Today. “It’s as dicey as I’ve seen, and I’ve been coming here for more than a year now.”

For many Iraqi journalists who are frequently out in the field, the threat of gunfire, particularly from U.S. troops, is also a major concern. “Our real fear is the Americans,” says Mohammed. “We fear them more than other people here.”

At least seven–and possibly as many as nine–journalists have been killed by U.S. gunfire since the war began in 2003. Most of them have been Iraqi or Arab, and several of the incidents have called into question the rules of engagement and conduct of U.S. troops, engendering deep mistrust among Arab journalists.

In March 2004, to protest the shooting deaths of two Iraqi journalists–Al-Arabiyya cameraman Ali Abdel Aziz and reporter Ali al-Khatib–by U.S. forces, Arab journalists walked out of a Baghdad press conference where U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell was speaking. Aziz and al-Khatib were killed by U.S. gunfire at a military checkpoint in Baghdad, where they had gone to cover the aftermath of a rocket attack. As the men departed the scene, U.S. troops opened fire when another car, driven by an elderly man, approached the soldiers and crashed into a small metal barrier near a military vehicle at the checkpoint.

These incidents involving U.S. troops have made journalists–not just Iraqis–extremely wary. AFP’s Dagher says that whenever he is on the road and passes a military convoy, he becomes apprehensive. “I am concerned that there might just be a knee-jerk reaction. … Whenever there are U.S. troops around … I feel that anything could happen that could trigger fire toward us.”

Arab journalists who approached or worked near U.S. troops have also faced various forms of harassment, including detention, physical abuse, and the confiscation of their film or equipment. In August, U.S. soldiers detained Associated Press (AP) photographer Karim Kadim and his driver, Mohammed Abbas, near Abu Ghraib Prison outside Baghdad. Both men were handcuffed, forced to stand in the sun for three hours, and denied water and the use of a telephone while soldiers kept their guns pointed at them, even though the journalists had told the troops they were members of the press. A U.S. military officer later apologized to the men and told AP’s Baghdad bureau that the arrests were a “misunderstanding.”

On January 2, U.S. troops detained Reuters cameraman Salem Ureibi, Reuters journalist Ahmad Mohammad Hussein al-Badrani, and their driver, Sattar Jabar al-Badrani, near Fallujah. The journalists say they came under U.S. fire while attempting to cover the aftermath of the downing of a U.S. helicopter by guerrillas and were later detained by U.S. soldiers. The three Iraqis were held for three days and allegedly subjected to abuse. The U.K.-based Guardian newspaper reported on January 13 that the journalists were blindfolded, forced to stand for hours with their arms raised, and threatened with sexual abuse. Citing a family member of one of the journalists, the paper said that U.S. interrogators forced one of the men to take off his clothes and put a shoe in his mouth. Repeated attempts to get comment from the U.S. military about this incident were unsuccessful.

According to reports, Al-Jazeera correspondents were arrested and abused in custody on at least two occasions while covering the aftermath of guerrilla attacks on U.S. troops. Al-Jazeera staff in Baghdad declined to speak with CPJ for this article. However, the U.S.-based magazine The Nation reported in March on the ordeal of Al-Jazeera cameraman Saleh Hassan, who was detained by U.S. forces in November 2003 after arriving at the scene of a roadside bombing of a U.S. convoy near the town of Baqouba, 25 miles (40 kilometers) north of Baghdad. U.S. troops interrogated Hassan and accused him of knowing about the attack before it happened. They then placed a hood over his head and transferred him to Abu Ghraib Prison, where, according to The Nation, soldiers “stripped him naked and addressed him only as “‘Al Jazeera,’ ‘boy,’ or ‘bitch.'” Hassan was “forced to stand hooded, bound, and naked for eleven hours … when he fell, soldiers kicked his legs to get him up again.” He was eventually released a month-and-a-half later, after an Iraqi Governing Council court found no evidence against him. Repeated attempts to get comment from the U.S. military about this incident were unsuccessful.

CPJ has called on the U.S. military to launch swift, thorough, and public investigations when U.S. troops are accused of harassing, detaining, or killing journalists. To date, military authorities have failed to provide thorough public accountings of many such incidents.

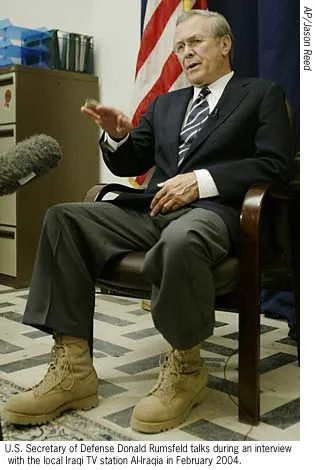

As in Hassan’s case, U.S. forces have repeatedly accused Arab satellite channels Al-Jazeera and Al-Arabiyya of having prior knowledge of attacks on coalition troops and continue to accuse them of inflaming anti-American sentiments. In a recent radio interview, U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said that both channels “are from time to time getting information before terrorist attacks even start. … So not only are they reporting things that aren’t true, but they’re in many cases … working in concert with the terrorists.”

Al-Jazeera and Al-Arabiyya have both repeatedly denied Rumsfeld’s charges. And Iraqi journalist Mohammed says that what the U.S. government sees as a conspiracy is really just doing the job well by getting to news scenes quickly. “It’s not much effort for me to discern where something took place. I know the streets of Fallujah, and if I see smoke or fire I go to the area immediately. I arrive at the scene, in the heart of the matter, at the beginning of an incident,” he explains. “So I call [my news agency] and report to them, or film. Now U.S. troops wonder, ‘How did we journalists know about the operations? … So now the Americans suspect that journalists are collaborating with the resistance. But we report the truth, the facts. We report what incidents are taking place.”

And while Iraqi media workers continue the difficult job of reporting the news and facilitating newsgathering, many wonder what can be done to protect them from insurgents, U.S. troops, and the risks inherent in covering any conflict.

“One area where news organizations could do better is by providing local staff with better safety equipment, such as flak jackets and armored cars,” says ABC News “Nightline” correspondent and CPJ board member Dave Marash, who recently spent two months in Iraq. While there, he saw firsthand the risks that Iraqi journalists face when Burhan Mohamed Mazhour, an Iraqi cameraman working for ABC, was killed by gunfire, possibly from U.S. troops, in the city of Fallujah.

“There is probably 10 percent of that risk that [is] reducible by measures we could take,” says one correspondent for a U.S. newspaper who requested anonymity. But, “They should all think very seriously about what they do for a living. In other words, they’re doing a job in which they can be killed, and they should be very sure they want to do it before coming to work every morning. What’s true for them is true for us, too.”

| Joel Campagna is CPJ’s senior program coordinator responsible for the Middle East and North Africa. Hani Sabra is CPJ’s Middle East and North Africa research associate. |