New York, August 23, 2007—The Committee to Protect Journalists is dismayed by reports of the assault, detention, and harassment of local journalists by security forces attempting to enforce the indefinite curfew imposed yesterday on the capital, Dhaka, and five other cities in response to growing unrest across the country. CPJ is also deeply concerned about warnings to the media from members of the interim government and from the military that have resulted in widespread self-censorship, particularly among broadcast outlets.

“Journalists must be free to report independently on the unfolding political crisis, without interference from security forces and without fear of retribution from the government,” said CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon. “The interim government so far has maintained that it is not imposing direct censorship, but it is clearly taking steps to control media coverage.”

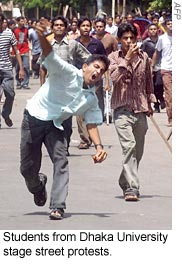

On Wednesday, the military-backed interim government announced an indefinite curfew in six urban centers that had been the scene of violent clashes between police and students calling for an end to emergency rule. Though officials had provided assurances that the media could operate freely during curfew hours without carrying special passes, dozens of journalists were assaulted and detained by members of the security forces in the course of their reporting, according to local news reports and CPJ sources.

Among those reportedly assaulted over the past two days were Anis Alamgir, head of the news department at Baishakhi TV; Kamrul Hasan Khan, a correspondent for the Daily Star newspaper; Kazi Saifuddin Avi and Rashed Ali, reporters for the daily Bhorer Kagoj; Nesar Ahmed, a reporter for the daily Amar Desh; Sabbir Mahmud, a reporter for the daily Korotoa; Jahangir Alam, of the United News of Bangladesh wire service; Babul Talukder, a photographer from the daily Dinkal; Sanaul Haque, a photographer for the daily New Age; Ainul Haque Royal, a reporter for the newspaper Bangladesh Today, and a photographer for the same daily identified only as Babu. The daily newspaper Samakal reported that 14 of its journalists were beaten up by members of the security forces.

Late on Thursday, the Press Information Department issued a notice directing print and electronic media personnel to obtain special curfew passes from the metropolitan police. Local journalists, however, told CPJ that there was an extreme shortage of passes available.

CPJ is also concerned about widespread self-censorship among local broadcast media following yesterday’s remarks by Mainul Hosein, adviser for law and information for the interim government, reminding journalists that emergency regulations were in force and urging the media to “play a responsible role.” He denied that the government was imposing direct censorship but reminded journalists that it was empowered to do so under the emergency provisions. In a pointed appeal to broadcasters, Hosein said, according to the BBC, “We request channels to stop televising footage of violence until further notice because this might instigate further violence.”

Private television channels in Bangladesh abruptly stopped carrying reports about the street demonstrations, suspending even the popular political discussion programs about the day’s news.

Today, two television channels—the private Ekushey Television and the 24-hour news network CSB TV—received a written notice from the Press Information Department warning them not to broadcast “provocative” news. Journalists from print and broadcast media outlets also have been receiving telephone calls from military intelligence officials instructing them to exercise greater caution in their reporting, according to CPJ sources.

“The political crisis will only be exacerbated by attempts to suppress news and opinion,” said Simon. “This government must not abuse the extraordinary powers it has under the state of emergency to keep the public in the dark.”

The Emergency Powers Rules of 2007, announced after the interim government took over in January, restrict press coverage of political news and set penalties of up to five years in prison for violations. The regulations allow the government to ban or censor print and broadcast news about rallies and other political activities that it deems “provocative or harmful.” Under the rules, the government can seize printed material and confiscate printing presses and broadcast equipment. The government also has power under the regulations to censor or block news transmitted in any form.