‘We returned from hell’: Palestinian journalists recount torture in Israeli prisons

- English

- العربية

In This Report

Content warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of physical, psychological, and sexual violence.

Palestinian journalist Ahmed Abdel Aal remembers the moment the ear-splitting music started. For five days, he said, he was held blindfolded in a room in an Israeli detention site, stripped and beaten, while loud Hebrew and English songs played at an unrelenting volume. Every time he drifted into unconsciousness, an electric shock or a blow jolted him awake.

Another journalist, who asked not to be named for fear of reprisals, described similar treatment inside what detainees refer to as the “disco room.” He said soldiers bound his genitals with zip ties and beat him until the injuries made it impossible to urinate without blood. “They told me that I would no longer be a man,” he said.

Their accounts are among 59 in-depth testimonies collected by the Committee to Protect Journalists from Palestinian journalists released from Israeli custody since October 7, 2023. These interviews revealed that 58 — all but one of those released — reported being subjected to what they described as torture, abuse, or other forms of violence since the onset of what human rights groups agree is a genocide.

CPJ has documented the detention of at least 94 Palestinian journalists and one media worker in that period – 32 journalists and one media worker from Gaza, 60 from the West Bank, and two in Israel. Thirty remain in custody, as of February 19, 2026. CPJ’s 2025 Prisons Census found that Israel has been listed as a top jailer of journalists since 2023

The organization attempted to contact all 65 journalists released from Israeli custody since October 7, 2023. One, Ismail al-Ghoul, was killed in an Israeli air strike, and the five others declined to speak.

CPJ could not independently verify each allegation, but the reports align with findings by human rights organisations documenting similar treatment of Palestinians in Israeli detentions, which Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem has described as a “network of torture camps.”

While conditions varied at different facilities, the methods those interviewed recounted — physical assaults, forced stress positions, sensory deprivation, sexual violence, and medical neglect — were strikingly consistent. Ten journalists requested anonymity, alleging explicit threats of re-arrest or death from Israeli interrogators and prison service officials if they spoke publicly. These threats appear in 31 of the individual testimonies, and have driven many journalists away from their work.

“These are not isolated incidents. Across dozens of cases, CPJ documented a recurring set of abuse – from beating to starvation, sexual violence, and medical neglect – directed at journalists because of their work. They expose a deliberate strategy to intimidate and silence journalists, and destroy their ability to bear witness. The continued silence from the international community only enables this.”

— CPJ Regional Director Sara Qudah

The vast majority — 48 of the journalists — were never charged with any crime and were held under Israel’s administrative detention system, which allows for an individual to be held without charge, typically for six months that can be renewed indefinitely, on the grounds of preventing them from committing a future offense. The remaining 10 were charged with incitement, anti-state activity, or promoting terrorism.

The UN Convention Against Torture, of which Israel is a ratified signatory, defines torture as the intentional infliction of severe physical or mental pain or suffering, for purposes of obtaining information or a confession, punishment, intimidation, coercion, or discrimination, when carried out by, at the instigation of, or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or person acting in an official capacity.

In November 2025, Peter Vedel Kessing, an expert on the United Nation’s Committee against Torture and Country Rapporteur, said, “the fact that Israel had ratified the Convention against Torture demonstrated the State’s willingness to eradicate and prevent torture and inhumane treatment. However, the Committee was deeply appalled by the large number of alternative reports received from a variety of sources of what appeared to be systematic and widespread torture and inhuman treatment of Palestinians, including children and other vulnerable groups”.

The journalists’ accounts describe a system built to silence them, and to ensure that stories from Gaza and the West Bank never make it out.

‘Game over’

On the day Israeli forces detained Shadi Abu Sido, a photojournalist from Gaza, a soldier leaned close to him inside Al-Shifa Medical Complex and said, in English: “Game over.”

What followed, he said, was a ritual detainees call “al-Tashreefeh”, or “the grand welcome”, the coordinated beating of detainees upon arrival to Israeli prisons. Upon transfer to Sde Teiman detention camp, he said, he was shackled, blindfolded, and forced through a corridor of soldiers who beat him with batons and kicks. He later learned he had a broken rib.

Similar accounts of abuse recur across most of the testimonies. Of the 59 journalists interviewed, 56 said they were repeatedly beaten inside prisons by authorities, as well as during arrest and transfer to the facilities.

Mustafa Khawaja, a journalist from the West Bank, said a beating on March 14, 2024, in Shatta prison left him with fractured ribs, meniscus tears, and spinal injuries later diagnosed as herniated discs. In Ktzi’ot prison, another detained journalist, Mohammed Badr, said he was struck so hard his tongue was cut. For two weeks, he could barely speak or eat.

At Ofer prison, radio journalist Mohammad al-Atrash described a coordinated assault in November 2023 that he and other detainees called “a Shin Bet party” or a “Ben-Gvir party” — a mass punishment involving dozens of prisoners.

Al-Atrash stated that trained dogs were ordered to attack the detainees, and metal instruments were used to create long-lasting bleeding and scars. Gazan journalists Islam Ahmed and Osama al-Sayed recounted the intermittent use of electroshocking and pepper spray between beatings.

According to several testimonies, the punishment took place shortly after a visit by Itamar Ben-Gvir, Israel’s national security minister. On multiple public platforms, the minister has stated that he was proud of the worsening conditions of Palestinian prisoners held in Israeli facilities. CPJ emailed Ben-Gvir and the Ministry of National Security for comment but received no response.

Others described injuries that lingered. Journalist Mohammed Nafez Qaoud said repeated beatings during intake left deep wounds on his feet. Without treatment, he said, they became infected with “worms feeding on them.”

Beyond physical assault, 36 journalists, roughly two-thirds, described being placed in forced stress positions.

Eleven cited the use of a method known as strappado, or what the Palestinian journalists termed “ghost hanging,” in which a person is hung, suspended by their arms, bound behind the back, and then pulled upward. Others said they were made to kneel or lay face forward for hours, as well as restrained under rain, direct sun, and sewage water.

One journalist, Sami al-Sai, said soldiers targeted the site of a recent kidney surgery despite his informing them of the operation.“We returned from hell,” Imad Ifranji told CPJ, using the term other detainees used for a section at Sde Teiman.

‘Disco room’

The United Nations Committee Against Torture (CAT), which monitors compliance with the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT), has found that the use of prolonged loud music or noise may constitute torture under Article 1 of the Convention when it causes severe physical or mental suffering, particularly when combined with other coercive practices.

At least 14 journalists told CPJ they were subjected to prolonged exposure to high-volume sound, including continuous amplified music, resulting in sleep deprivation and sensory disorientation in Israeli detention facilities, particularly at Sde Teiman, a practice also documented by other human rights groups. Additional testimonies described round-the-clock dog barking that they said exacerbated their psychological distress.

At least seven, including Abdel Aal, reported that they were held for days in what they called “disco rooms,” where speakers blasted music at such intensity that sleep became impossible.

Freelance journalist Hatem Hamdan, who was rearrested on February 5, 2026, reported being confined for approximately nine hours in a prison transport vehicle while exposed to continuous loud music in Hebrew.

Lama Khater stated that during interrogation, she was blindfolded and forced to listen to documentaries on the attacks by Hamas and other Palestinian militant groups on southern Israel on October 7, 2023, prior to questioning.Osama al-Sayed, Yousef Sharaf, and Imad Ifranji reported the use of high-intensity sound bombs during detention after being arrested at Al-Shifa’ Medical Complex.

Medical neglect

Medical neglect emerged as one of the most pervasive forms of reported abuse, often compounding injuries reportedly suffered during beatings or interrogations. CPJ documented 27 accounts of medical neglect and, in several cases, the complicity of health workers in violence against detainees.

Journalist Yousef Sharaf said wounds from repeated beatings became infected in the poor sanitary conditions of the prisons, forming abscesses across his body. He said that after going without medical care from prison authorities, another detainee, Dr. Nahed Abu Taima, an imprisoned surgeon from Nasser Medical Complex, performed improvised procedures using what detainees believed was cleaning bleach.

Journalist Thaer Fakhoury told CPJ he sustained a severe eye injury during beatings in Etzion and Ofer detention facilities, resulting in temporary loss of vision for approximately 20 days. He stated that medical treatment was denied. Mohammed Imad Sultan, prior to being killed in an Israeli airstrike in western Gaza upon his release, similarly reported eye injuries and denial of medical care.

CPJ documented reports of widespread scabies, unexplained rashes and boils, wounds stitched without anaesthesia, untreated bone fractures and eye injuries, asthma attacks, and the deliberate neglect of serious pre-existing and newly sustained health conditions. Journalists also described unsanitary living conditions, chronic food shortages, and the complete lack of sanitary products for women.

Several said they avoided medical staff altogether, saying doctors themselves inflicted or condoned abuse.Abdul Mohsen Shalaldeh told CPJ and the Tadamon Centre that he was burned by lit cigarettes extinguished on his bare body. When he reported the abuse to an attending physician in detention, the physician responded, “It’s okay, no problem.” Another journalist who was detained recalled a doctor responding to a serious injury by saying, “Why did you call me if he isn’t dead yet?”

Starvation

International humanitarian law explicitly prohibits the use of starvation as a method of punishment or coercion in detention settings. CPJ found that food deprivation was repeatedly described not only as physical suffering, but as a tool used to break detainees psychologically.

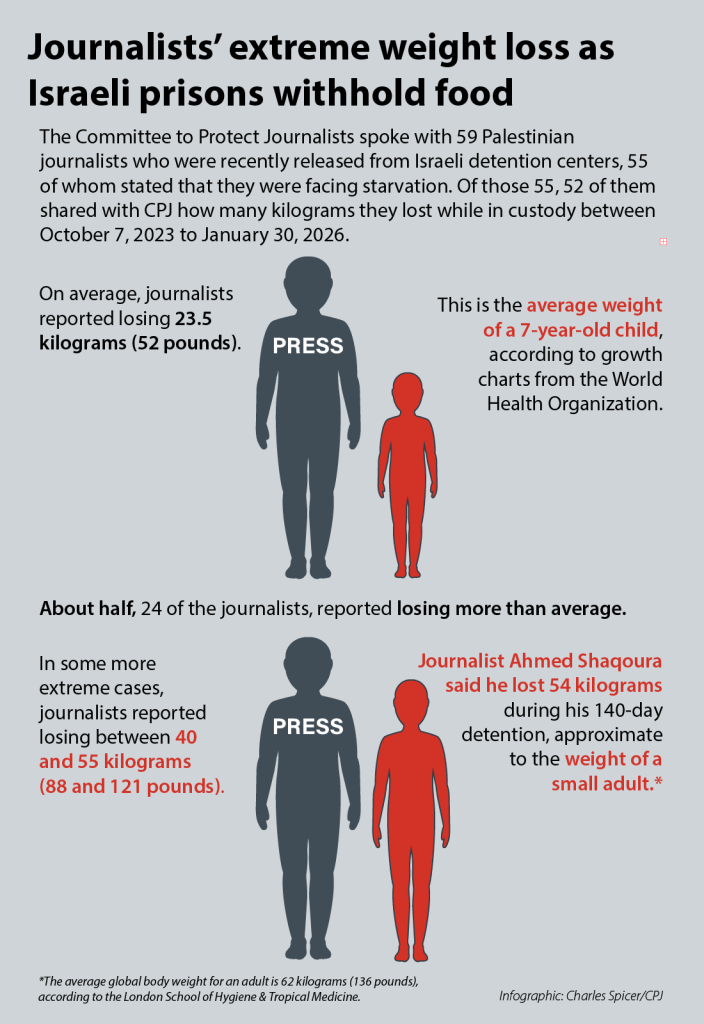

Fifty-five of the 59 journalists interviewed reported extreme hunger or malnutrition. CPJ calculated an average weight loss of 23.5 kilograms (54 pounds) among the group by comparing journalists’ reported weight before and after detention.

Photographs provided to CPJ show dramatic transformations, with journalists displaying gaunt faces, protruding ribs, and hollowed cheeks.

Ahmed Shaqoura said he lost 54 kilograms (119 pounds) during 14 months in Israeli custody in Ktzi’ot and Al-Jalama prisons. Others described surviving on moldy bread and rotten food, and generally inadequate quantities of food.

Journalist Ashwaq Ayad said she lost more than 15 kilograms (33 pounds) and began vomiting blood after being denied appropriate food and treatment for a pre-existing medical condition.

During winter, the lack of clothing forced trade-offs. One journalist, Abdelhameed Hamdona, said he swapped his food for a shirt.Israel’s national security minister Ben-Gvir said in July 2025 “I am here to ensure that the ‘terrorists’ receive the minimum of the minimum [of food].” Although Israel’s top court ruled in September that deliberate starvation is illegal, journalists released in recent months say they saw no improvement.

Sexual violence

Sexual violence, documented by other rights groups in Israeli prisons, appears repeatedly in the testimonies, with journalists describing assaults intended to humiliate, terrorize, and permanently scar them.

In December 2025, German journalist Anne Liedtke, detained aboard a Gaza-bound flotilla, alleged Israeli soldiers raped her while in custody. Italian journalist Vincenzo Fullone and Australian activist Surya McEwen made similar accusations.

Two of the 59 Palestinian journalists also told CPJ they were raped in detention.

Journalist Sami al-Sai said he was taken to a small cell in Megiddo prison, and soldiers removed his trousers and underwear, and penetrated him with batons and other objects.

Al-Sai recalls that he has not spoken about this rape during detention, “I did not speak to anyone inside the prison about what happened, except for two senior detainees who have been imprisoned for 25 years.” Al-Sai said he fell into a severe psychological state and was only able to emerge from it after hearing testimonies from other detainees. He said “I remained silent for nearly two months, but I ultimately decided to speak out about what happened to me.”

Another journalist, Osama al-Sayed, said he and other detainees were stripped naked and attacked by trained dogs in Sde Teiman. He described the incident as rape, adding that soldiers laughed while filming the assault.

In total, CPJ documented 17 journalist testimonies involving sexual violence and 19 more describing humiliating strip searches. The alleged acts included assaults on the journalists’ genitals, attempted forced penetration with objects, forced nudity and recording, threats of rape, and other methods of sexualized coercion.

Threats

Multiple journalists told CPJ they were explicitly targeted because of their work.

Mohammed Badr said interrogators questioned him for hours about his journalism and gave him a choice of becoming an informant or remaining longer in prison.

Amin Baraka said that he was repeatedly interrogated for his work with Qatar-affiliated Al Jazeera and threatened with violence against his family.

“An Israeli soldier told me, word for word in Arabic, that Al Jazeera correspondent Wael Al-Dahdouh defied us and stayed in the Gaza Strip, so we killed his family, and we will kill yours too,” he said.

Mohammed al-Atrash said before he was released from prison he was warned to stop working in journalism. “They told me if you write as much as “good morning” on your socials, we will find out,” he said.

Osama al-Sayed said that during his detention, soldiers referred to him as “Jazeera.” He cited heightened abuse when he declared that he is a journalist. Al-Sayed explained that during his arrest he told the soldiers, “I am a journalist and this is when I was beaten up gravely.” Shadi Abu Sido, who was arrested while filming, said the soldier that detained him said, “you will learn the meaning of journalism in Tel Aviv there.”

No accountability

The Israeli military did not respond to CPJ’s repeated requests for comment on specific allegations by journalists, instead requesting ID numbers and geographic coordinates that CPJ does not collect or provide. When asked about allegations of physical, sexual abuse and starvation, and the investigation and accountability process, an army spokesperson said “individuals detained are treated in accordance with international law,” adding that the armed forces “have never, and will never, deliberately target journalists,” and that any violations of protocol “will be looked into.”

CPJ also emailed the Israel Prison Service (IPS) regarding the allegations. In response, the IPS said “all prisoners are detained according to the law” and that “all basic rights are fully upheld by professionally trained prison guards.” The service said it was unaware of the claims described, and that to its knowledge “no such events have occurred,” but noted that the “prisoners and detainees have the right to file a complaint that will be fully examined and addressed by official authorities.”

Human rights groups, however, report that these complaint mechanisms are largely ineffective, and in some cases, expose detainees to further harm. Journalist Farah Abu Ayash, who was not interviewed by CPJ as she remains imprisoned, stated in a testimony made public by her lawyer that she was slapped by a soldier upon her detention and forced to kiss the Israeli flag. Abu Ayash said she filed a complaint against the soldier involved, but prison conditions deteriorated and she was held in solitary confinement for over 50 days, and subjected to routine beatings and starvation. CPJ emailed the Israeli Prison Services to follow up on the complaint Abu Ayash said she submitted but received no reply.

Journalists also widely reported not being allowed access to their lawyers, an experience broadly reflected by what other right groups have reported. At least 21 said they were denied adequate legal representation, with 17 stating they were not allowed to speak to a lawyer at all. A further four said they were permitted to see a lawyer only once, for a few minutes and under non-private conditions.

In an April 2024 communiqué between CPJ and UN Human Rights Office, it was noted that some detained journalists were denied access to lawyers and family, leaving them isolated throughout administrative detention, and undermining their legal representation.

Additionally, while legal representation is formally provided through the Palestinian Authority-administered Commission of Detainees Affairs (CDA), the system appears to be overstretched. UN Human Rights reported that only four lawyers were assigned to administrative detention cases, each carrying a caseload of approximately 900 detainees.

A system of impunity – not an aberration

Reported allegations of torture, abuse and violence in Israeli prisons are not new and are not limited to journalists. Israeli and international rights groups have, for years, documented patterns of abuse against civilian Palestinian detainees – including journalists. A recent report by Physicians for Human Rights–Israel documented at least 90 Palestinian deaths in Israeli custody, according to the organization, meet the threshold of torture under Article 1 of the Convention Against Torture, as well as to medical neglect.

In early 2025, leaked surveillance footage from Sde Teiman detention camp appeared to show soldiers sexually assaulting detainees, triggering a national scandal. The footage was aired by Israeli journalist Guy Peleg, who has since reported facing threats and harassment.

The testimonies collected by CPJ suggest that what Palestinian journalists experienced over the past two years is not the result of rogue individuals but a systematic pattern of detention practices that rely on violence, humiliation, and deprivation to intimidate journalists and suppress reporting from Gaza and the West Bank.

“These are not isolated incidents,” said CPJ Regional Director Sara Qudah. “Across dozens of cases, CPJ documented a recurring set of abuse – from beating to starvation, sexual violence, and medical neglect – directed at journalists because of their work. They expose a deliberate strategy to intimidate and silence journalists, and destroy their ability to bear witness. The continued silence from the international community only enables this.”

The scale, consistency, and severity of those documented abuses raise serious questions under international law, including potential violations of the UN Convention Against Torture, and Article 79 of the Geneva Conventions’ protections for journalists.

Breaking this cycle requires more than the release of the 30 Palestinian journalists still held in Israeli prisons, who were not included in this report. Of those still imprisoned, 25 have no disclosed charges.

While the Israel–Gaza war is defined by profound political, military, and humanitarian consequences, this context does not diminish the need to address the particular risks faced by Palestinian journalists. Israel must allow independent international monitors, including UN special rapporteurs, access to detention facilities and conduct transparent, impartial investigations into all allegations. The international community must break its silence and press for accountability and ensure violations of international law do not go unpunished, and that the cost of reporting does not remain unbearable.

Methodology summary

This report is based on in-depth interviews conducted by CPJ’s research team with 59 Palestinian journalists released from Israeli detention between October 2023 to January 2026. Interviews were conducted via phone and online messaging services and transcribed verbatim. Participants were asked standardized questions covering the circumstances of their arrest, detention conditions, legal status, alleged abuse, and health impact. Interviewees were offered anonymity. And, where available, they provided supporting documentation such as photographs, medical reports, and legal documents. Reported claims of abuse and torture were analyzed for patterns across multiple testimonies and cross-checked against publicly available reporting and prior documentation by human rights organizations.

CPJ corroborated the information collected through multiple sources. Where possible, testimonies were cross-checked against documents provided by the interviewees and independently verified public sources, including media reporting, prior human rights documentation, and limited medical records. The report also reflects engagement with Israeli authorities through requests for Right of Response (ROR), and documents both responses received and instances where no response was provided. This methodology ensures transparency in both the systematic collection of information and the verification of allegations while acknowledging limitations due to restricted access, security concerns, and gaps in documentary evidence.

CPJ uses the term “torture” in this report to reflect the language used by detainees and human rights organizations. CPJ does not make legal determinations, but reports documented accounts, patterns, and expert assessments.

Credits

Rama Sabanekh has been CPJ’s researcher for the Levant since November 2025. A third-generation Palestinian refugee based in Amman, Jordan, she holds an MA in War Studies from King’s College London and a BA in Politics and Economics from SOAS, University of London. With an academic and professional focus on the political geography and history of the region, she has worked with a range of independent news and media outlets as a freelance contributor, senior editor, researcher, and producer. Rama has worked in English and Arabic across multiple media platforms and has collaborated closely with grassroots groups advocating for feminism, queer rights, and labor rights.

Mohammed Othman joined CPJ as a Middle East and North Africa researcher, focusing on Gaza and the West Bank, in August 2024. He has worked in the media since 2009, specializing in investigative journalism, in addition to reporting for the regional press freedom group SKeyes.

Kholod Massalha is a CPJ consultant on Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory and a researcher with years of experience in press freedom and freedom of expression issues.

Featured image: A Palestinian flag is pictured on the fence of Israel’s Ofer prison near the city of Ramallah in the occupied West Bank, on July 12, 2021. (Photo: AFP/Abbas Momani)