As of December 1, 2016

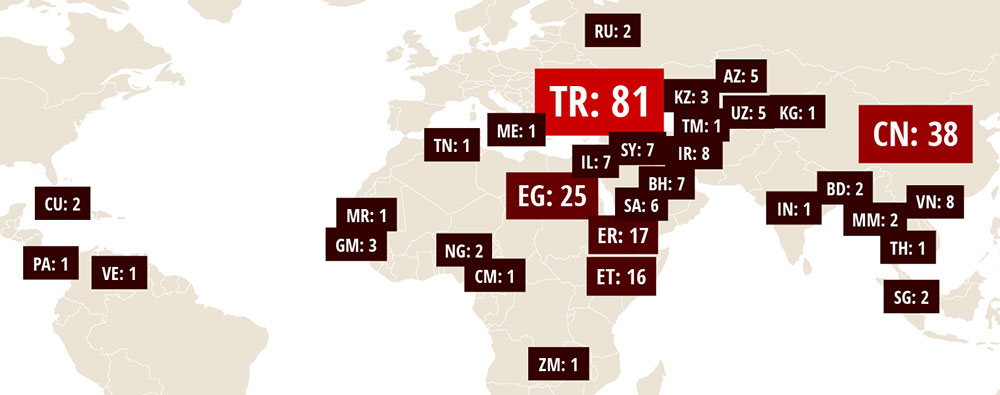

Analysis: Turkey’s crackdown leads to record high | CPJ Methodology | Blog: Imprisoned in Panama | Blog: Weighing China cases | Video: Turkey: A Prison For Journalists | Video: Prison Census 2016

Click on a country name to see summaries of individual cases.

Medium

Charges

Freelance / Staff

Health Problems

Foreign / Local

Gender

Azerbaijan: 5

Nijat Aliyev, Azadxeber

Aliyev, editor-in-chief of the independent news website Azadxeber, was detained near a subway station in downtown Baku and charged with possession of illegal drugs. Colleagues disputed the charges and said they were in retaliation for his journalism. Aliyev’s deputy, Parvin Zeynalov, told local journalists that the outlet’s critical reporting on the government’s religion policies, including perceived anti-Islamic activities, could have prompted the editor’s arrest.

CPJ has documented a pattern in which Azerbaijani authorities file questionable drug charges against journalists whose coverage has been at odds with official views.

Aliyev’s lawyer, Anar Gasimli, told the local press freedom group Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety that Aliyev said investigators tortured him in custody and forced him to admit he had drugs in his possession. The institute quoted another lawyer for the journalist, Yalchin Imamov, as saying that two of Aliyev’s teeth were broken and his ear injured.

In January 2013, authorities brought additional charges against Aliyev–illegal import and sale of religious literature, making calls to overturn the constitutional regime, and incitement to ethnic and religious hatred, the institute reported. In March 2013, investigators finished the investigation against the editor, according to local press reports.

On December 9, 2013, the Baku Court for Grave Crimes sentenced Aliyev to 10 years in prison, according to the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel. In June 2014, Azerbaijan’s Court of Appeals denied Aliyev’s appeal, reports said.

In April 2016, the Supreme Court of Azerbaijan denied Aliyev’s appeal, the independent TV station Meydan TV reported. In July 2016, the journalist’s attorney told the independent Azerbaijani news agency Turan that he planned to file a complaint with the European Court for Human Rights, but authorities were withholding the text of the verdict, which is required to file a complaint.

CPJ could not determine the state of the journalist’s health in late 2016.

Araz Guliyev, Xeber 44

Guliyev, chief editor of news website Xeber 44, was arrested on hooliganism charges in September 2012 while reporting on a protest in the southeastern city of Masally, news reports said. Residents were protesting about dancers at a festival who they claimed were not properly clothed, reports said. Police arrested the demonstrators, who were calling on the festival organizers to respect religious traditions.

During Guliyev’s pretrial detention, authorities expanded his charges to include “illegal possession, storage, and transportation of firearms,” “participation in activities that disrupt public order,” “inciting ethnic and religious hatred,” “resisting authority,” and “offensive action against the flag and emblem of Azerbaijan.”

Guliyev’s brother, Azer, told the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel that his brother’s imprisonment could be related to his coverage of protests against an official ban on headscarves and veils in public schools. Xeber 44 covers news about religious life in Azerbaijan and international events in the Islamic world. The journalist’s lawyer told Kavkazsky Uzel that investigators claimed to have found a grenade while searching Guliyev’s home, but his lawyer said the investigators had planted it.

In April 2013, the Lankaran Court on Grave Crimes convicted Guliyev of all charges and sentenced him to eight years in prison.

Guliyev’s lawyer, Fariz Namazli, told the local press freedom organization Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety that the charges against the journalist were not substantiated in court and that the testimony of witnesses conflicted. The lawyer said that Guliyev had been beaten by authorities after his arrest and that he was not immediately granted access to a lawyer.

News reports said that Guliyev filed an appeal, which was denied by regional courts. In July 2014, the Supreme Court of Azerbaijan upheld the journalist’s sentence. In Azerbaijan, a case cannot be appealed once the Supreme Court has ruled.

Guliyev was being held at Prison No. 14, outside Baku, according to Kavkazsky Uzel and an August 2014 report on political prisoners in Azerbaijan by a group of lawyers, human rights defenders, and non-governmental organizations. In late 2016, CPJ could not determine the state of his health.

Seymur Hazi, Azadliq

Police in the eastern Absheron district arrested Hazi, a reporter for the opposition newspaper Azadliq, over claims that he attacked a man at a bus stop, the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported. The day after his arrest, the Absheron District Court ordered the journalist, who also uses the name Haziyev, to be held in pretrial detention for two months, the report said. He was charged with hooliganism.

Authorities said that while waiting for a bus on his way to work, Hazi beat a Baku resident named Magerram Hasanov, according to Kavkazsky Uzel. Hazi said in court that he had acted in self-defense, Kavkazsky Uzel reported. He said Hasanov had insulted and attacked him. Elton Guliyev, the journalist’s lawyer, told Kavkazsky Uzel that he believed authorities had orchestrated the altercation because police arrived moments after it started. Guliyev said he believes Hazi was imprisoned in retaliation for his journalism.

Hazi often criticized the Azerbaijani government’s domestic and foreign policies in his reports for Azadliq, according to Kavkazsky Uzel. As a host for Azadliq‘s online TV program “Azerbaijan Saati” (Azerbaijani Hour), he was critical of government corruption and human rights abuses.

Hazi was sentenced to five years in jail on January 29, 2015. A court upheld the sentence on September 29, 2015, according to the local press freedom group, Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety.

In 2016, Hazi received the Free Media Award, presented jointly by the Olso-based Fritt Ord and the Hamburg-based ZEIT-Stiftung Ebelin und Gerd Bucerius foundations, for reporting on corruption and the abuse of power.

Hazi is being held at Baku Investigative Prison No. 1. In late 2016, CPJ could not determine the state of his health.

Afgan Sadygov, Azel

Sadygov, the founder and chief editor of regional news website Azel, was arrested outside the eastern city of Jalilabad on November 22, 2016, on charges of aggravated assault, and authorities ordered him detained for three months pending investigation, according to news reports.

Sadygov reported on allegations of corruption in the local administration for Azel, and managed the Facebook page “Our Jalilabad” on which he often criticized local authorities.

The charge relates to an incident on August 9, 2016, when the head of the city’s executive branch, Aziz Azizov, summoned the journalist to the city administration, according to local and international media reports. Azizov allegedly asked the journalist to remove his critical reports and allegedly offered him money to cease reporting, his lawyer Elchin Sadygov (no relation) told the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel.

Azizov did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment in late 2016.

Afghan Sadygov refused the offer and left the office. In the hallway of the building, he was attacked and punched by a woman who then filed a complaint against him, according to news reports citing his lawyer and family.

The journalist was charged with assault, according to the Azeri service of the U.S.-government funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. If found guilty Sadygov faces up to five years in prison.

Sadygov’s mother, Ulnisa, told Kavkazsky Uzel that the accusations against her son were related to his journalism. “My son has managed this website for many years practically alone. He covered issues related to lawlessness, injustice. He was warned and requested to stop criticizing local authorities in his reports. They wanted him to write only praising articles but my son refused,” she said.

Ulnisa Sadygova told Kavkazsky Uzel that police tortured the journalist but did not specify what had allegedly happened to him. She said that her requests to visit the journalist were denied. Sadygov is being held in the Kurdakhani pre-trial detention center in Baku, his lawyer told CPJ. The lawyer said that Sadygov needs medical assistance, but did not specify the reason why.

Ikram Rahimov, Hurriyet

An Azerbaijani court on November 25, 2016 convicted Rahimov, editor of the online news agency Realliq, of libel and sentenced him to one year in prison, according to news reports. The charge relates to a May 25, 2016, story in the opposition news website Hurriyet, where Rahimov worked at the time. The story alleged extortion by a Sumqayit city official and tax evasion at a local chain of stores, reports said.

In the report Rahimov referred to a document that he said came from the state tax agency, and quoted an individual named Rahman Novruzov, who he said had informed him of the alleged wrongdoing. Novruzov was also sentenced to a year in prison for libel, according to reports.

In the article, Rahimov alleged that the head of the city administration, Zakir Farajev, instructed the stores to be closed, and allowed them to open only after receiving a bribe. Among the defense witnesses was a head of the chain who sustained the accusations of extortion, according to media reports.

When asked for comment by the news website Contact, the city administration denied Farajev was connected to the case and said that Farajev called the accusation “total nonsense.”

The website Hurriyet is no longer active. A message on its home page says the site has been suspended.

Rahimov’s lawyer, Elchin Sadygov, told CPJ that after the court hearing, the journalist wassent to the Sumqayit police department instead of to a prison, which is a violation of procedure. Sadygov said that the journalist was kept in the facility, which is meant for pre-trial detention, for three days and was tortured by police to extract an apology to Farajev. Police put a plastic bag over Rahimov’s head and beat him, the lawyer said. Sadygov said Rahimov was left needing medical help.

In a letter given to his lawyer during a prison visit November 29, Rahimov gave a detailed account of how he was tortured for three days, according to news reports. According to local media, the Interior Ministry denied the allegations of torture. Ministry spokesman Orkhan Mansurzada described the claims as “unfounded.”

On November 29, 2016, Rahimov was transferred to a prison in Shuvelan, about 70 kilometers from Sumqayit.

Bahrain: 7

Abduljalil Alsingace, Freelance

Alsingace, a blogger and human rights defender, was among a number of high-profile government critics arrested as the government renewed its crackdown on dissent after pro-reform protests in February 2011.

In June 2011, a military court sentenced Alsingace to life imprisonment for “plotting to topple the monarchy.” In all, 21 bloggers, human rights activists, and members of the political opposition were found guilty on similar charges and handed lengthy sentences.

On his blog, Al-Faseela (Sapling), Alsingace wrote critically about human rights violations, sectarian discrimination, and repression of the political opposition. He also monitored human rights for the Shia-dominated opposition Haq Movement for Civil Liberties and Democracy. He was first arrested on anti-state conspiracy charges in August 2010 as part of widespread reprisals against political dissidents, but was released in February 2011 as part of a government effort to appease a then-nascent protest movement.

In September 2012, the High Court of Appeal upheld Alsingace’s conviction and life sentence, along with those of his co-defendants. Four months later, on January 7, 2013, the Court of Cassation, the highest court in the country, also upheld the sentences.

In 2015, Alsingace began refusing all solid food to protest the conditions at Jaw Central Prison, where he is being held. He ended his protest on January 28, 2016 after refusing solid food for 313 days, according to Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain.

In November 2015, Alsingace was temporarily released to allow him to attend his mother’s funeral.

A family member, who asked for anonymity for fear of retribution, told CPJ in October 2016 that Alsingace was not receiving adequate medical care, including for injuries suffered during torture. According to findings by the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry, Alsingace was “sexually molested with a finger thrust into his anus” and repeatedly beaten with fists and batons. One officer placed a pistol in his mouth and said, “I wish I could empty it in your head.” Security forces threatened to rape his daughter, the inquiry found. The commission was established by King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa in June 2011 to investigate the 2011 protest movement and subsequent crackdown, including allegations of abuse of prisoners, including Alsingace. Its findings and recommendations, based on interviews with inmates, officials, witnesses, and human rights defenders, were officially endorsed by King Hamad in November 2011.

Ahmed Humaidan, Freelance

Humaidan, a freelance photojournalist, was sentenced to 10 years in prison on March 26, 2014, in a trial of more than 30 individuals charged with participating in a 2012 attack on a police station on the island of Sitra, according to news reports. The reports said three defendants were acquitted, and the rest were given three to 10 years in prison.

Humaidan was at the station to document the attack as part of his coverage of unrest in the country after anti-government protests erupted in February 2011, according to news reports. His photographs were published by local opposition sites, including the online newsmagazine Alhadath and the news website Alrasid.

Adel Marzouk, head of the Bahrain Press Association, an independent media freedom organization based in London, told CPJ that Humaidan’s photographs had exposed police attacks on protesters during demonstrations. Humaidan’s family said authorities had sought his arrest for months and had raided their home five times to try to arrest him, news reports said.

The High Court of Appeals upheld Humaidan’s sentence on August 31, 2014, despite calls by CPJ and other human rights organizations to throw out the conviction.

In 2014, the U.S. National Press Club honored Humaidan with its John Aubuchon Press Freedom Award.

Humaidan is being held in Jaw Central Prison.

Hussein Hubail, Freelance

Hubail, a photographer who documented opposition protests, was sentenced to five years in prison on April 28, 2014, on charges of inciting protests against public order, according to news reports. Eight other individuals were sentenced in the same trial, including online activist Jassim al-Nuaimi and artist Sadiq al-Shabani, the reports said.

In January 2016, Hubail was informed that he had been sentenced to an additional year imprisonment on a charge of participating in an illegal gathering, the Bahrain Press Association reported.

Hubail was arrested at Bahrain International Airport and held incommunicado for six days before being transferred to Dry Dock prison on August 5, 2013, the Bahrain Center for Human Rights reported.

The arrest came amid political tension in Bahrain over an opposition protest planned for August 14, 2013, modeled on the demonstrations that led to the ouster of Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi. Bahrain King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa decreed new measures to crack down on protesters who the government believed were engaging in terrorist activities.

On August 7, 2013, Hubail was questioned by the public prosecutor, who accused him of incitement against the regime and calling for illegal gatherings. Hubail’s lawyer, Ali al-Asfoor, said in a series of Twitter posts that investigators had questioned Hubail about his photography and purported posts on social media that had called for the protests on August 14.

Hubail’s work has been published by Agence France-Presse and other news outlets. In May 2013, the independent newspaper Al-Wasat awarded him a photography prize for his picture of protesters enshrouded in tear gas.

Hubail said he was tortured in custody by the Criminal Investigation Department, according to the Bahrain Center for Human Rights. The center said Hubail told of being beaten, kicked, forced to stand for long periods of time, and deprived of sleep. The Bahraini Information Affairs Authority told CPJ on August 28, 2013, that the government was investigating the torture claims. CPJ sent a written request for comment in October 2016 to the Information Affairs Authority asking about the outcome of the investigation. As of late 2016, it had not received a response.

The High Court of Appeals upheld Hubail’s five-year sentence on September 21, 2014, according to news reports.

In April 2015, someone familiar with Hubail’s situation, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, told CPJ that the photographer’s health had deteriorated and he had been denied adequate medical care for a heart condition. The journalist is being held in Jaw Central Prison. His health had improved in 2016.

Sayed Ahmed al-Mosawi, Freelance

Al-Mosawi was detained on February 10, 2014, during a raid by authorities to arrest his brother, Mohammed, according to news reports. Security forces spotted al-Mosawi’s camera in the apartment and asked who it belonged to, someone who spoke with al-Mosawi after his arrest and who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, told CPJ. After conferring over the radio, security forces arrested al-Mosawi as well. The freelance photographer was transferred to Dry Dock jail after being questioned about his work.

Al-Mosawi’s internationally recognized photographs, most of which he posted on social networking sites, have won several awards. His work includes a range of subjects such as wildlife and daily life in Bahrain in addition to anti-government protests, a frequent occurrence in Bahrain since the government cracked down on large-scale demonstrations in 2011.

The journalist told his family in a phone call from prison in 2014 that he had been beaten and given electric shocks, according to the Bahrain Center for Human Rights.

On November 23, 2015, al-Mosawi, his brother, and 11 other defendants were found guilty of participating in a terror organization that committed acts of violence against police forces, according to court documents reviewed by CPJ in 2016. The court sentenced al-Mosawi to 10 years’ imprisonment and revoked his citizenship.

According to the prosecution, al-Mosawi and other employees at VIVA, a cell phone provider where he also worked, helped other defendants illegally procure SIM cards under false identities for terror purposes.

According to the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, the government has frequently abused an overly broad definition of terrorism as a tool to suppress dissent and independent reporting. Since 2012, Bahrain has revoked the citizenship of more than 130 Bahrainis, including journalists, human rights defenders, and accused terrorists, according to local human rights groups.

On June 13, 2016, the public prosecutor announced that an appeals court had upheld al-Mosawi’s sentence.

Al-Mosawi is being held in Jaw Central Prison.

Mahmoud al-Jaziri, Al-Wasat

Police arrested Mahmoud al-Jaziri from his home in Nabih Saleh Island, south of the capital Manama, on the morning of December 28, 2015. He was allowed to call his brother later that day to say he was being held as part of a criminal investigation, local human rights groups and his paper Al-Wasat reported.

The Interior Ministry named al-Jaziri, a reporter for the independent daily Al-Wasat, as among those arrested for allegedly plotting terrorist attacks funded by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Hezbollah, according to a January 1, 2016 report by the official Bahrain News Agency. That announcement came amid a diplomatic rift between Iran and Saudi Arabia and its allies, including Bahrain, after Saudi Arabia executed prominent Shiite cleric Nimr Al-Nimr. It also followed years of official persecution–including the 2011 death in custody of a founding investor–of Al-Wasat staff.

On January 4, 2016, two days after al-Nimr’s execution, al-Jaziri was referred to a special prosecutor for terrorist crimes who charged him with supporting terrorism, inciting hatred of the regime, having contacts with a foreign country, and seeking to overthrow the regime by joining the banned political group, the Al-Wafaa Islamic Party, and the February 14 Youth Movement, which have organized anti-government protests since the 2011 uprising, according to news reports. The Interior Ministry statement carried by Bahrain News Agency listed al-Jaziri and three other co-accused as members of an armed wing of Al-Wafaa that was plotting bombings in cooperation with Iran’s Revolutionary Guard and Hezbollah.

Mansoor al-Jamri, editor-in-chief of Al-Wasat and CPJ’s 2011 International Press Freedom Awardee, told CPJ that al-Jaziri denied the charges and told prosecutors his relationship with Al-Wafaa did not extend beyond proofreading the group’s public statements, an activity he stopped after becoming a professional journalist in 2012. Al-Jamri said al-Jaziri covers parliamentary news for Al-Wasat.

Al-Jaziri was arrested on the same day that a report he had written was published on a member of parliament’s proposal to deny housing to Bahrainis whose citizenship had been revoked for political activities.

Over the course of 2013-14, he wrote a series of opinion articles for Al-Wasat in which he blamed world and regional powers for what he called the “failures” of the 2011 uprisings collectively known as the “Arab Spring,” criticized the lack of compromise in the region’s conflicts, and called for closer relationships between predominantly Sunni and Shiite countries in the region.

According to the Bahrain Press Association, al-Jaziri’s family said he was blindfolded for an unspecified number of days after his arrest. The family said he was banned from sitting or sleeping for three days during questioning and before he signed a confession, unaware of its content.

On June 28, 2016, the public prosecutor announced the commencement of a trial of 18 suspects, including al-Jaziri and another journalist, Ali Mearaj. The defendants are accused of belonging to an Iranian and Hezbollah-backed terror cell formed by the banned al-Wafaa party.

As of late 2016, Al-Jaziri was held in Dry Dock jail pending the outcome of his trial.

Ali Mearaj, Freelance

Bahraini security forces arrested Mearaj on June 5, 2016 at the Manama airport, only two months after he was released from prison where he had been serving a sentence on separate charges also related to his journalism, his brother Mohammed told CPJ.

On June 28, 2016, Mearaj’s trial began with 17 other defendants, including Al-Wasat journalist Mahmoud al-Jaziri, on charges of belonging to an Iranian and Hezbollah-backed terror cell formed by the banned al-Wafaa political party.

The Bahraini Interior Ministry named al-Jaziri, a reporter for the independent daily Al-Wasat, as among those arrested for allegedly plotting terrorist attacks funded by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Hezbollah, according to a January 1, 2016 report by the official Bahrain News Agency (BNA).

On January 4, al-Jaziri was referred to a special prosecutor for terrorist crimes, who charged him with supporting terrorism, inciting hatred of the regime, contacting a foreign country and giving it information, and seeking to overthrow the regime by joining Al-Wafaa and the February 14 Youth Movement, which has organized protests since the 2011 uprising, according to news reports.

During this time, Mearaj was in prison in relation to a different case, and his name was not mentioned in any of the public announcements concerning the case. According to his brother Mohammed, Mearaj was not questioned after his new arrest or informed of charges against him before the June 28, 2016 hearing.

Before the new charge, Mearaj had been serving a two and a half year term on charges of “insulting the king” and “misusing communication devices” in relation to posts he was accused of writing on the opposition website Lulu Awal, according to news reports.

Mearaj’s appeal in that case was repeatedly postponed as the government claimed a witness failed to appear in court, according to his brother Mohammed. On April 5, 2016, the appeals court reduced his sentence to one and a half years in jail, the Bahrain Press Association reported. Having already served two years while waiting for his appeal, he was released on April 7.

Mearaj is currently held in Dry Dock jail pending the outcome of his trial. By late 2016, the government had not publicly disclosed information or details of evidence as to why he had been added to the case.

Faisal Hayyat, Freelance

Hayyat was arrested on October 9, 2016, after receiving a call to report to the interior ministry, according to Al-Wasat and a post on Hayyat’s Twitter account.

On the day of Hayyat’s arrest, the state-run Bahrain News Agency reported that the Ministry of Interior had ordered the arrest of a man for defamatory statements about a religious sect in Bahrain. The agency, which did not the name the person arrested, reported that he was referred to the public prosecutor under article 309 of the penal code, which outlaws speech that ridicules a recognized religious sect under penalty of up to a year in prison or a fine not exceeding 100 dinar (approximately US$265).

The arrest came after Hayyat published a series of tweets during the observance of Ashura, when Shia Muslims mourn the death of Hussein in battle against the Sunni Muslim Caliph Yazid Ibn Muawiya in 680 AD. The observance is often a tense time in Bahrain, where a Sunni monarchy rules over a majority Shia population.

In the tweets on October 7, 2016, Hayyat called on God to curse Yazid and leaders of his army who fought against Hussein. In one tweet, he wrote, “If today we’ve come to disagreement over the crimes of Yazid, then tomorrow we’ll disagree about Satan and it will be criminalized to curse him too.”

A criminal court sentenced Hayyat to three months in prison on November 29, 2016, according to news reports.

Four prominent Bahraini human rights groups pointed to a different reason for Hayyat’s arrest however. On October 1, 2016, Hayyat posted on his Facebook page a widely shared public letter to the Minister of Interior over his arrest and torture in 2011. In the letter, he writes “Every day I witness dignity and humanity crushed in your prisons.” He continues, “I write this letter knowing that it could make me lose my freedom and my story may once again be the story of a detainee, but my faith in the judgment and power of God is greater than my fear.”

The letter refers to Hayyat’s April 2011 arrest after Bahraini state television identified him as one of the “traitors” participating in a protest for greater press freedom. He was held for nearly three months. After his release, he claimed he was repeatedly beaten by officers, including while tied in the “shrimp” position with his hands and feet hogtied behind his back as he lay on his stomach. Hayyat accused one officer of pulling down his pants in the courtyard of the police station, while onlookers watched as Hayyat pleaded to not be raped. Hayyat said the officer pulled up Hayyat’s pants, made Hayyat face the wall, and began to grope him while pressing his body into Hayyat’s backside.

CPJ considers article 309 of Bahrain’s penal code, like many other provisions criminalizing speech in the country, overly broad and ambiguous, allowing the government to arbitrarily apply the law to silence critical and independent voices.

Before his 2011 arrest, Hayyat worked as a sports commentator. He more recently produced videos on YouTube on social issues and current affairs. In August 2016, he created the SnapHayyat YouTube channel, where he posts Snapchat-style videos of his commentary on politics and current affairs.

Bangladesh: 2

Salah Uddin Shoaib Choudhury, Weekly Blitz

A Dhaka court sentenced Choudhury, an editor of the Bangladeshi tabloid Weekly Blitz, to seven years in prison in relation to his articles about the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Bangladesh.

Choudhury was convicted of harming the country’s interests under section 505(A) of the penal code, having been found to have intentionally written distorting and damaging materials, reports said. Choudhury had written about anti-Israeli attitudes in Muslim countries and the spread of Islamist militancy in Bangladesh.

The prosecutor in the case, Shah Alam Talukder, told Agence France-Presse that Choudhury was taken to prison after the verdict. The editor’s family said that an appeal of the decision to the High Court is pending, news reports said. No details about his state of health, or where he is being held, had been disclosed as of late 2016.

Choudhury was arrested in November 2003 when he tried to travel to Israel to participate in a conference with the Hebrew Writers Association. Bangladesh has no diplomatic relations with Israel, and it is illegal for Bangladeshi citizens to travel there. Choudhury was released on bail in 2005.

He was charged with passport violations, but the charges were dropped in February 2004 and he was accused of sedition, among other charges, in connection with his articles, according to news reports. The editor was not convicted on the sedition charge, the reports said. He was arrested again in 2012 in connection with embezzlement charges, and the current charges relating to his writing were filed. In Bangladesh, judicial proceedings can take years to resolve. In February 2015, Choudhury was sentenced to four years in prison on the embezzlement charges, according to news reports.

Abdus Salam, Ekushey TV

Salam, the owner of Ekushey TV, was accused of sedition and being in violation of Bangladesh’s Pornography Act, according to reports. Some journalists said in news reports and to CPJ that the arrests were related to a speech by Tarique Rahman, the son of opposition leader Khaleda Zia, which was broadcast by the channel on January 5, 2015.

Salam was arrested at Ekushey TV’s offices in Dhaka on January 6, 2015, alongside Kanak Sarwar, a former senior correspondent for the privately owned broadcaster, according to local news reports. At a press conference in Dhaka after Salam’s arrest, Information Minister Hasanul Haq Inu said police had charged the chairman of the channel under the Pornography Control Act of 2012. Police said a woman filed a complaint in November 2014 saying she had been vilified in a news program, according to reports. The police said Ekushey TV, which covers local and national news, aired pornographic images of the woman, news reports said. The channel denies the accusations, reports said.

Salam was also charged with sedition, according to news reports. Authorities claim he confessed to being guilty of sedition in a statement before a judge on January 19, 2015, news reports said.

In March 2015, Sarwar was arrested under the Pornography Act after Salam was said to have confessed to charges brought against him, reports said. According to news reports, Sarwar, who was fired from Ekushey TV in the days after the speech was aired, was later released on bail. In September 2016, authorities issued a warrant for the arrest of another former Ekushey TV correspondent, Mahathir Faruqui Khan, in relation to the broadcasting of Rahman’s speech. Khan had not been arrested as of late 2016, according to news reports.

In the speech aired by Ekushey TV on January 5, 2015 Rahman, the senior vice chairman of opposition leader Zia’s party, called for the toppling of the Sheikh Hasina-led government, reports said. Rahman, who has been in exile since 2008 and faces corruption charges in Bangladesh, is a fierce critic of Hasina’s father, the founder of the country.

Ekushey TV was unavailable in some parts of the country after the airing of Rahman’s speech, according to local and international news reports. Cable operators said they were instructed to take Ekushey TV off the air, according to Agence France-Presse. Authorities denied issuing any order, reports said.

Zia, who had been confined to her office earlier in the year after calling on her supporters to topple the Hasina-led government, accused the government of interrupting Ekushey TV broadcasts.

Cameroon: 1

Ahmed Abba, Radio France Internationale

Ahmed Abba, a correspondent for Radio France Internationale’s (RFI) Hausa service, was arrested as he left a press briefing at the office of a local governor in Maroua, the capital of Cameroon’s far north region, on July 30, 2015 according to RFI. He was taken to the capital, Yaoundé. The journalist was denied access to his lawyer until October 19, RFI told CPJ. Officials did not take a statement from Abba until November 13, more than three months after his arrest, which is against the law, according to news reports that cited his lawyers.

RFI cited one of the journalist’s lawyers, Charles Tchoungang, as saying Abba was interrogated in relation to the activities of the extremist sect Boko Haram, which has renamed itself the Islamic State in West Africa. Formed in 2002, Boko Haram, which is based in northern Nigeria, has been increasing its presence in northern Cameroon since 2014, according to news reports. The group is known for mass kidnappings and targeted attacks on civilians.

Abba’s trial began on February 29, 2016, according to reports that cited Tchoungang and a second lawyer, Nakong Clement. A military tribunal charged the journalist with complicity in acts of terrorism and failure to denounce acts of terrorism under the country’s 2014 anti-terrorism law, news reports said. According to prosecutors, Abba did not inform authorities he had been in contact with members of Boko Haram. The maximum sentence for the charges is the death penalty.

Abba pleaded not guilty at a hearing on August 3, 2016, reports said. The next hearing was scheduled for December 7, 2016, according to news reports.

RFI reported that Abba mostly covered refugee issues in the region but had also covered attacks carried out by Boko Haram. In a statement issued in June 2016, RFI said Abba’s reporting had been professional and called for his immediate release.

China: 38

Yang Tongyan (Yang Tianshui), Freelance

Yang, known by his pen name Yang Tianshui, was detained along with a friend in Nanjing, eastern China. He was tried on charges of subverting state power and, on May 17, 2006, the Zhenjiang Intermediate People’s Court sentenced him to 12 years in prison.

Yang was a well-known writer and member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He was a frequent contributor to U.S.-based websites banned in China, including Boxun News and Epoch Times. He often wrote critically about the ruling Communist Party and advocated the release of jailed internet writers.

According to the verdict in Yang’s case, which was translated into English by the U.S.-based prisoner advocacy group Dui Hua Foundation, the harsh sentence was over a fictitious online election, established by overseas Chinese citizens, for a “democratic Chinese transitional government.” His colleagues said he was elected to the leadership of the fictional government without his prior knowledge. He later wrote an article in Epoch Times in support of the model.

Prosecutors also accused Yang of transferring money from overseas to Wang Wenjiang, a Chinese dissident jailed for endangering state security. Yang’s defense lawyer argued that this money was humanitarian assistance to Wang’s family and should not have constituted a criminal act.

Believing that the proceedings were fundamentally unjust, Yang did not appeal. He had already spent 10 years in prison for his opposition to the military crackdown on demonstrators at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

In June 2008, Shandong provincial authorities refused to renew the law license of Yang’s lawyer, press freedom advocate Li Jianqiang. In 2008, the PEN American Center announced that Yang had received the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award.

Yang’s health deteriorated in 2015. He has pleural tuberculosis, nephritis, diabetes, high blood pressure, and other conditions, according to Radio France Internationale. Because Yang maintains he is innocent, his medical parole applications have been rejected. To demand his right to proper medical care, Yang has staged hunger strikes, according to Radio France Internationale.

Yang is being held in Nanjing No. 1 Prison in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, according to Radio Free Asia. In late 2016, Hua Chunhui, a democracy activist who has spoken with a friend of the columnist, told CPJ that Yang’s health problems persist.

Qi Chonghuai, Freelance

Tengzhou police arrested Qi and charged him with fraud and extortion. He was sentenced initially to four years in prison on May 13, 2008, but new charges and a longer sentence was added the year he was due to be released. The arrest occurred about a week after police detained Qi’s colleague, Ma Shiping, a freelance photographer, on charges of carrying a false press card.

Qi, a journalist for 13 years, and Ma had criticized a local official in Shandong province in an article published June 8, 2007, on the website of the U.S.-based Epoch Times, according to Qi’s lawyer, Li Xiongbing. On June 14, 2007, the two posted photographs on the Xinhua news agency’s anti-corruption Web forum that showed a luxurious government building in the city of Tengzhou. Ma was sentenced in 2007 to one and a half years in prison. He was released in 2009, according to Qi’s wife, Jiao Xia.

Qi was accused of taking money from local officials while reporting several stories, a charge he denied. The people from whom he was accused of extorting money were local officials threatened by his reporting, Li said. Qi told his lawyer and Jiao that police beat him during questioning on August 13, 2007, and again during a break in his trial.

Qi was due to be released in 2011, but in May of that year local authorities told him the court had received new evidence against him. On June 9, 2011, less than three weeks before the end of his term, a Shandong provincial court sentenced him to an additional eight years in prison, according to the New York-based advocacy group Human Rights in China and Radio Free Asia.

Human Rights in China, citing an online article by defense lawyer Liu Xiaoyuan, said the court tried Qi on a new count of stealing advertising revenue from China Security Produce News, a former employer. The journalist’s supporters speculated that the charge was in reprisal for Qi’s statements to his jailers that he would continue reporting after his release, according to The New York Times.

Qi was being held in Tengzhou Prison, a four-hour trip from his family’s home, which limits visits. Jiao told journalists in 2012 that her husband offered her a divorce, but she declined. Jiao also said that Qi had told her that he had been tortured in prison. He said some of his teeth were knocked out when he was beaten by prison officials, and he has been forced to mine coal. Qi also suffered from arthritis, according to a transcript of Jiao’s full account.

Ekberjan Jamal, Freelance

On two occasions in November 2007, Ekberjan used his cell phone to record sounds of riots in his home town of Turpan. The audio files, which included the noise of rioters, sirens, and a voice-over of Ekberjan describing what was happening, were sent to friends in the Netherlands, and later used in news reports by Radio Free Asia and Phoenix News in Hong Kong. Ekberjan posted links to the news reports on his blog, which was closed by authorities on December 25, 2007, according to the rights group World Uyghur Congress.

In an April 2009 Radio Free Asia report, Ekberjan’s mother said he made the recordings on two occasions, but at his trial he faced 21 counts of sending information abroad. She told Radio Free Asia she believed he might have been motivated to send the files to help achieve his ambition of studying abroad. The Turpan Intermediate People’s Court sentenced him to 10 years in prison on February 28, 2008 for “separatism” and revealing state secrets, crimes under articles 103 and 11 of the Chinese penal code.

As of April 2009, he was being held in the Xinjiang Number 4 prison in Urumqi, Radio Free Asia reported.

Uighur rights groups contacted by CPJ in late 2016 said they had no new information in his case.

Liu Xiaobo, Freelance

Liu, a longtime advocate of political reform and the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was imprisoned on charges of inciting subversion through his writing. Liu was an author of Charter 08, a document promoting universal values, human rights, and democratic reform in China, and was among its 300 original signatories. He was detained in Beijing shortly before the charter was officially released, according to international news reports.

Liu was charged with subversion in June 2009 and was tried in the Beijing No. 1 Intermediate Court in December of that year. Diplomats from the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Sweden were denied access to the trial, the BBC reported. On December 25, 2009, the court convicted Liu of inciting subversion and sentenced him to 11 years in prison and two years’ deprivation of political rights.

The verdict cited several articles Liu had posted on overseas websites, including the BBC’s Chinese-language site and the U.S.-based websites Epoch Times and Observe China, all of which had criticized Communist Party rule. Six articles were named, including pieces headlined, “So the Chinese people only deserve ‘one-party participatory democracy?'” and “Changing the regime by changing society,” as evidence that Liu had incited subversion. Liu’s income was generated by his writing, his wife told the court.

The court verdict cited Liu’s authorship and distribution of Charter 08 as further evidence of subversion. The Beijing Municipal High People’s Court upheld the verdict in February 2010.

In October 2010, the Nobel Prize committee awarded Liu its 2010 peace prize “for his long and nonviolent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.”

Liu’s wife, Liu Xia, has been under house arrest in her Beijing apartment since shortly after her husband’s detention. In March 2013, unidentified assailants beat two Hong Kong journalists when they filmed an activist’s attempt to visit her at home. In February 2014, Liu Xia spent a brief period in a hospital for heart problems, depression, and other medical conditions. Wu Yangwei, a dissident who writes under the name Ye Du, told CPJ in late 2016 that police have prohibited him and other dissident intellectuals from seeing her.

Hu Jia, a democracy activist and friend of Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia, told CPJ that in 2016 police have allowed Liu Xiaobo’s wife to visit him once a month and on his birthday.

In June 2013, Liu’s brother-in-law, Liu Hui, a manager of a property company, was convicted of fraud in what the journalist’s family said was reprisal for Liu Xiaobo’s journalistic work. The conviction stemmed from a real-estate dispute that Liu Hui’s lawyers said had already been settled. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison, news reports said. A court rejected his appeal in August 2013. Liu Hui was released on medical parole later that year, Hu Jia told CPJ. The police threatened Liu Xia, saying that if she spoke with the foreign media they would put her brother back in jail, according to Hu Jia.

Liu Xiaobo was being held in Jinzhou Prison in northeastern China’s Liaoning province, according to news reports. Hu Jia, citing Liu Xia, told CPJ that the journalist has no health issues.

Kunchok Tsephel Gopey Tsang, Chomei

Public security officials arrested the online writer Tsang in Gannan, a Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in the south of Gansu province, according to Tibetan rights groups. Tsang ran the Tibetan cultural issues website Chomei, according to the India-based Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy. Kate Saunders, U.K. communications director for the International Campaign for Tibet, told CPJ that she learned of his arrest from two sources.

The detention appeared to be part of a wave of arrests of writers and intellectuals in advance of the 50th anniversary of the March 1959 uprising preceding the Dalai Lama’s departure from Tibet. The 2008 anniversary had provoked ethnic rioting in Tibetan areas, and international reporters were barred from the region.

In November 2009, a Gannan court sentenced Tsang to 15 years in prison for disclosing state secrets, according to The Associated Press.

Tsang’s family is allowed to visit him in prison every two months, and is permitted to speak with him only in Chinese via an intercom and separated by glass screen. Not being allowed to converse in Tibetan is difficult for many of his family members, PEN International said.

Tsang is currently held at Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture Cooperation Prison, according to the Hong Kong-based group Chinese Human Rights Defenders.

Memetjan Abdulla, Freelance

Abdulla, editor of the state-run China National Radio Uighur service, was detained in July 2009 and accused of instigating ethnic rioting in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region through postings on the Uighur-language website Salkin, which he managed in his spare time, according to international news reports. A court in the regional capital, Urumqi, sentenced him to life imprisonment on April 1, 2010, the reports said. The exact charges against Abdulla were not disclosed.

The U.S. government-funded Radio Free Asia reported on the sentence in December 2010, citing an unnamed witness at the trial. Abdulla was targeted for talking to international journalists in Beijing about the riots and for translating articles on the Salkin website, Radio Free Asia reported. The World Uyghur Congress, a rights group based in Germany, confirmed the sentence with contacts in the region, according to The New York Times.

Abdulla is in an unspecified prison in Xinjiang, according to the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China, which monitors human rights and law in China. CPJ could not determine the state of his health in late 2016.

Niyaz Kahar, Golden Tarim

Kahar, a reporter and blogger, disappeared during ethnic rioting in Urumqi in July 2009. His family announced in February 2014 that he had been convicted of separatism and was being held in Shikho prison outside Shikho city in the far north of Xinjiang, according to the Uighur service of the U.S.-funded Radio Free Asia.

Kahar worked as a local reporter before launching the Uighur-language website Golden Tarim, which featured articles on Uighur history, culture, politics, and social life.

With the unrest surrounding the riots, it is difficult to determine the exact date of his arrest or where he was initially held. His family had questioned police and government authorities after his disappearance, but received no information, and assumed he had been killed until they were informed of his conviction in 2010, Radio Free Asia reported.

The family was told that Kahar was sentenced to 13 years in prison during a closed court session in Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, though they did not know the date of the trial. Kahar’s sister Nurgul told Radio Free Asia that during their search for Kahar, the family was told by court officials in Urumqi that he “published illegal news and propagated ideas of ethnic separatism on his website. He was charged with the crime of splitting the nation.”

According to a September 2015 report by Radio Free Asia, Kahar’s health is failing. His family is allowed only a 15-minute visit with the journalist every four months. “He is losing his courage year by year,” Radio Free Asia cited his mother as saying. CPJ was unable to determine the details of his poor health or any updates to his status in late 2016.

Thousands of Uighurs remain unaccounted for in Xinjiang. Many were detained during the 2009 crackdown or other security sweeps by Chinese authorities.

Gulmire Imin, Freelance

Imin was one of several administrators of Uighur-language Web forums who were arrested after the July 2009 riots in Urumqi, in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. In August 2010, Imin was sentenced to life in prison on charges of separatism, leaking state secrets, and organizing an illegal demonstration, a witness to her trial told the U.S. government-funded broadcaster Radio Free Asia.

Imin held a local government post in Urumqi. She contributed poetry and short stories to the cultural website Salkin and had been invited to moderate the site in late spring 2009, her husband, Behtiyar Omer, told CPJ. Omer confirmed the date of his wife’s initial detention in a statement at the Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy in 2011.

Authorities accused Imin of being an organizer of demonstrations on July 5, 2009, and of using the Uighur-language website to distribute information about the event, Radio Free Asia reported. Imin had been critical of the government in her online writing, readers of the website told Radio Free Asia. The website was shut down after the riots and its contents were deleted.

Imin was also accused of leaking state secrets by phone to her husband, who lives in Norway. Her husband told CPJ that he called her on July 5, 2009, but only to check whether she was safe.

The riots, which began as a protest over the death of Uighur migrant workers in Guangdong province, turned violent and resulted in the deaths of 200 people, according to the official Chinese government count. Chinese authorities blocked access to the internet in Xinjiang for months after the riots, and hundreds of protesters were arrested, according to international human rights organizations and local and international media reports.

Imin was being held in the Xinjiang women’s prison (Xinjiang No. 2 Prison) in Urumqi, according to the rights group World Uyghur Congress. CPJ could not determine the status of her health in late 2016.

Gheyrat Niyaz (Hailaite Niyazi), Uighurbiz

Security officials arrested Niyaz, a website manager who is sometimes referred to as Hailaite Niyazi, in his home in the regional capital, Urumqi, according to international news reports. He was convicted of endangering state security and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

According to reports, Niyaz was punished because of an August 2, 2009, interview with Yazhou Zhoukan (Asia Weekly), a Chinese-language magazine based in Hong Kong. In the interview, Niyaz said authorities had not taken steps to prevent violence before ethnic unrest in July 2009 in China’s far-western Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region.

Niyaz, who once worked for the state newspapers Xinjiang Legal News and Xinjiang Economic Daily, managed and edited the website Uighurbiz until June 2009. A statement posted on the website quoted Niyaz’s wife as saying that although he had given interviews to international media, he had no malicious intentions.

Authorities blamed local and international Uighur sites for fueling the violence between Uighurs and Han Chinese in the predominantly Muslim Xinjiang region.

According to the Hong Kong-based group Chinese Human Right Defenders, as of late 2016 Niyaz was being held in Changji prison in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. CPJ was unable to determine the state of his health or the conditions under which he is being held.

Liu Xianbin, Freelance

A court in western Sichuan province sentenced Liu to 10 years in prison on charges of inciting subversion through articles published on overseas websites between April 2009 and February 2010, according to international news reports. One article was titled “Constitutional Democracy for China: Escaping Eastern Autocracy,” according to the BBC.

Liu also signed Liu Xiaobo’s pro-democracy Charter 08 petition. (Liu Xiaobo, who won the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize for his actions, is serving an 11-year term on the same charge.)

Police detained Liu Xianbin on June 28, 2010, according to the U.S.-based prisoner rights group Laogai Research Foundation. He was sentenced in 2011 during a crackdown on bloggers and activists who sought to organize demonstrations inspired by uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa, according to CPJ research.

Liu spent more than two years in prison for involvement in the 1989 anti-government protests in Tiananmen Square. He later served 10 years of a 13-year sentence handed down in 1999 after he founded a branch of the China Democracy Party, according to The New York Times.

Liu is being held at Chuanzhong prison in Sichuan province, according to China Change, a website tracking human rights in the country. His friend and fellow writer, Zhao Hui, told CPJ in late 2016 that Liu is in good health.

Li Tie, Freelance

Police in Wuhan, Hubei province, detained Li, a 52-year-old freelancer, in September 2010, according to international news reports. The Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court tried him behind closed doors on April 18, 2011, but did not announce the verdict until January 18, 2012, when he was handed a 10-year prison term and three additional years’ political deprivation, according to news reports citing his lawyer. Only Li’s mother and daughter were allowed to attend the trial, news reports said.

The court cited 13 of Li’s online articles to support the charge of subversion of state power, a more serious count than inciting subversion, which is a common criminal charge used against jailed journalists in China, according to CPJ research. Evidence in the trial cited articles including one headlined “Human beings’ heaven is human dignity,” in which Li urged respect for ordinary citizens and called for democracy and political reform, according to international news reports. Prosecutors argued that the articles proved Li had “anti-government thoughts” that would ultimately lead to “anti-government actions,” according to the Hong Kong-based Chinese Human Rights Defenders.

Jian Guanghong, a lawyer hired by his family, was detained before the trial and a government-appointed lawyer represented Li instead, according to the group. Prosecutors also cited Li’s membership in a small opposition group, the China Social Democracy Party, the group reported.

Li is in Edong prison in Huanggang, Hubei province, according to Boxun News. He was not allowed to communicate with people outside of the prison through phone calls or letters. Li has high blood pressure, according to Chinese Human Rights Defenders.

CPJ’s calls to a relative of Li for updates on his case and health went unanswered in late 2016.

Jin Andi, Freelance

Beijing police detained Jin, a freelance writer, Lü Jiaping, a military scholar, and Lü’s wife, Yu Junyi, on allegations of inciting subversion in 13 online articles they wrote and distributed together, according to international news reports and human rights groups.

A Beijing court sentenced Lü to 10 years in prison and Jin to eight years in prison on May 13, 2011 for subverting state power, according to the Hong Kong-based advocacy group Chinese Human Rights Defenders. Yu, 71 at the time, was given a suspended three-year sentence and kept under residential surveillance, which was lifted in February 2012, according to the group and the English-language, Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post, and the U.S. government-funded Voice of America. Lü, who was in his 70s when arrested, was granted medical parole in February 2015 due to his deteriorating health, according to BBC Chinese.

The court maintains that the three defendants “wrote essays of an inciting nature” and “distributed them through the mail, emails, and by posting them on individuals’ Web pages. [They] subsequently were posted and viewed by others on websites such as Boxun News and New Century News,” according to a 2012 translation of the appeal verdict published online by William Farris, a lawyer in Beijing. The 13 articles, which were principally written by Lü, were listed in the appeal judgment, along with dates, places of publication, and the number of times they were reposted. One 70-word paragraph was reproduced as proof of incitement to subvert the state. The paragraph said in part that the Chinese Communist Party’s status as a “governing power and leadership utility has long since been smashed and subverted by the powers that hold the Party at gunpoint.”

Jin is serving his sentence in Xi’an Prison in Shaanxi province, according to China Political Prisoner Concern, a human rights website based in New York. CPJ could not determine any new information in his case in late 2016.

Chen Wei, Freelance

Police in Suining, Sichuan province, detained Chen alongside dozens of lawyers, writers, and activists who were jailed nationwide after anonymous online calls for a nonviolent “Jasmine Revolution” in China, according to international news reports. The Hong Kong-based group Chinese Human Rights Defenders reported that Chen was charged on March 28, 2011 with inciting subversion of state power.

Chen’s lawyer, Zheng Jianwei, made repeated attempts to visit him but was not allowed access until September 8, 2011, according to the rights group and the U.S. government-funded broadcaster Radio Free Asia. Radio Free Asia reported that police had selected four pro-democracy articles Chen had written for overseas websites as the basis for criminal prosecution.

In December 2011, a court in Suining sentenced Chen to nine years in prison on charges of “inciting subversion of state power.”

Chen has been jailed twice before. He served a year and a half in prison for participating in the Tiananmen protests in 1989. In 1992 he was sentenced to five years in prison for organizing the Chinese Freedom and Democracy Party.

He is being held in Jialin prison in Sichuan province, according to Boxun News.

Gartse Jigme, Freelance

Police arrested Jigme, a Tibetan author and monk, at the Rebgong Gartse monastery in the Malho prefecture of Qinghai province, according to news reports. His family was unaware of his whereabouts until a Qinghai court sentenced him to five years in prison on May 14, 2013. The charges have not been disclosed officially, but the independent Chinese PEN Center said he was accused of separatism.

The conviction was in connection with the second volume of Jigme’s book, Tsenpoi Nyingtob (The Warrior’s Courage), according to Voice of America and Radio Free Asia. The book contained chapters expressing Jigme’s opinions on topics such as Chinese policies in Tibet, self-immolation, minority rights, and the Dalai Lama, according to news reports.

Jigme was briefly detained in 2011 in connection with the first volume of his book, according to the Hong Kong-based group Chinese Human Rights Defenders and Tibetan rights groups. He had written the book as a reflection on widespread protests in Tibetan areas in the spring of 2008, Tibetan scholar Robert Barnett told CPJ. China has jailed scores of Tibetan writers, artists, and educators for asserting Tibetan national identity and civil rights since the protests.

Authorities did not disclose any information on Jigme’s health or whereabouts. According to the Independent Chinese PEN Center, he may be in prison in Xining, a city in Qinghai province. In late 2016, CPJ was unable to verify if he was in jail in Xining or determine the condition of his health.

Liu Wei’an, Freelance

The Shaoguan People’s Procuratorate, a state legal body, issued a statement in June 2013 that said Liu and Hu Yazhu had been arrested in Guangdong province after confessing to accepting bribes while covering events in the northern city of Shaoguan.

Hu and Liu were sentenced to 13 years and 14 years in prison respectively in June 2014 for accepting bribes and for extortion, according to Shaoguan Daily, a government-run newspaper.

Liu, a freelance writer, and Hu, a staff reporter for the official Guangdong Communist Party newspaper Nanfang Daily, had both written articles published in 2011 in Nanfang Daily and on news websites about a dispute involving the illegal extraction of rare minerals in Shaoguan, according to news reports.

The prosecutors’ statement said Hu and Liu accepted 493,000 yuan (about US$82,200) in bribes. The pair were stripped of their press cards and banned from journalism for life, according to the state-run paper China Daily.

Users on Weibo, China’s microblog service, said they suspected the reporters’ arrests were in retaliation for their reports that exposed problems in the government and judiciary.

Details of the journalists’ whereabouts were not included in local reports about their case. CPJ could not determine the state of their health in late 2016.

Hu Yazhu, Nanfang Daily

The Shaoguan People’s Procuratorate, a state legal body, issued a statement in June 2013 that said Hu and Liu Wei’an had been arrested in Guangdong province after confessing to accepting bribes while covering events in the northern city of Shaoguan.

Hu and Liu were sentenced to 13 years and 14 years in prison respectively in June 2014 for accepting bribes and for extortion, according to Shaoguan Daily, a government-run newspaper.

Hu, a staff reporter for the official Guangdong Communist Party newspaper Nanfang Daily, and Liu, a freelance writer, had both written articles published in 2011 in Nanfang Daily and on news websites about a dispute involving the illegal extraction of rare minerals in Shaoguan, according to news reports.

The prosecutors’ statement said Hu and Liu accepted 493,000 yuan (about US$82,200) in bribes. The pair were stripped of their press cards and banned from journalism for life, according to the state-run paper China Daily.

Users on Weibo, China’s microblog service, said they suspected the reporters’ arrests were in retaliation for their reports that exposed problems in the government and judiciary.

Details of the journalists’ whereabouts were not included in local reports about their case. CPJ could not determine the state of their health in late 2016.

Dong Rubin, Freelance

Dong was detained in Kunming city, Yunnan province, on accusations of misstating his company’s registered assets, according to statements from his lawyer. On July 23, 2014, he was sentenced by Wuhua Court in Kunming to six years and six months in prison on charges of illegal business activity and creating a disturbance, according to the Hong Kong-based group Chinese Human Rights Defenders.

Dong, who runs an internet consulting company, used the name “Bianmin” on his microblog to criticize authorities and raise concerns about local issues. He also used the microblog to campaign in 2009 for an investigation into the death of a young man in police custody. Authorities had initially said the man’s death was an accident but later admitted he had been beaten to death, according to news reports. In 2013, Dong raised safety and environmental concerns about a state-owned oil refinery planned near the city of Kunming and expressed support on his microblog for a protest against the project by Kunming residents in May 2013.

Dong predicted his arrest when he wrote on his microblog, which had about 50,000 followers, that strangers had raided his office in late August and taken three computers. “What crime will they bring against me?” Dong wrote. “Prostituting, gambling, using and selling drugs, evading tax, causing trouble on purpose, fabricating rumors, running a mafia online?”

Dong’s friend, Zheng Xiejian, told Reuters in September 2013, “If they want to punish you, they can always find an excuse. They could not find any wrongdoing against Dong and had to settle on this obscure charge.”

Although Dong is not a professional journalist, CPJ determined that he was jailed in connection with his news-based commentary published on the internet. From August 2013, authorities detained scores of people in a stepped-up campaign to banish online commentary that, among other issues, casts the government in a critical light, according to Chinese media and human rights groups.

During his trial Dong said he was questioned for seven to eight hours at a time for more than 70 days, while chained to a chair, according to Chinese Human Rights Defenders. He is in frail condition, the Hong Kong-based group stated.

Dong is being held at Wuhua prison in Yunnan province, his friend and democracy activist, Li Huaping, told CPJ in late 2016.

Yao Wentian (Yiu Man-tin), Morning Bell Press

Yao Wentian, a Hong Kong publisher and honorary member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center, was placed under residential surveillance in Shenzhen, in China’s southern Guangdong province, by state public security officers on October 27, 2013, on “suspicion of smuggling ordinary goods” before he was detained on November 2. Yao’s son, Edmond Yao, said his father had been preparing to publish a book titled Chinese Godfather Xi Jinping by the exiled U.S.-based Chinese author Yu Jie. A previous book by Yu that Yao published, which criticized former Premier Wen Jiabao, is banned in China.

Yao was accused of falsely labeling and smuggling industrial chemicals. His family said he was delivering industrial paint to a friend in Shenzhen. At his trial, prosecutors said the cost of the industrial chemicals Yao was accused of smuggling from Hong Kong amounted to more than 1 million yuan (US$163,000), according to reports.

On May 7, 2014 during a closed-door trial at the Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court, Yao was sentenced to the maximum 10 years in prison. According to family members, he is being held in Dongguan prison in Guangdong province. Yao, who is elderly, is in poor health, the family says, because he is forced to do hard labor and is not receiving medical treatment. CPJ’s email to a relative of the journalist asking for updates in late 2016 did not receive a response.

Yao started his publishing business, Morning Bell Press, in Hong Kong in the 1990s. The small business has published many books by Chinese dissident writers.

Ilham Tohti, Uighurbiz

Tohti, a Uighur scholar, writer, and blogger, was taken from his home by police on January 15, 2014, and the Uighurbiz website he founded, also known as UighurOnline, was closed. The site, which Tohti started in 2006, was published in Chinese and Uighur, and focused on social issues.

Tohti was charged with separatism by Urumqi police on February 20, 2014. He was accused of using his position as a lecturer at Minzu University of China to spread separatist ideas through Uighurbiz. On September 23, 2014, at the Urumqi Intermediate People’s Court, Tohti was sentenced to life imprisonment. He denied the charges.

Several foreign governments and human rights organizations protested the sentence. The European Union released a statement condemning the life sentence as unjustified. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said the U.S. was concerned by the sentencing and called on Chinese authorities to release him, along with seven of his students.

Tohti’s appeal request was rejected at a hearing in a Xinjiang detention center on November 21, 2014 that was scheduled at such short notice that his lawyer was unable to attend.

Tohti’s wife told Radio Free Asia in February 2016 that authorities allow family members to visit Tohti for only 30 minutes every three months.

Seven of his students–Perhat Halmurat, Shohret Nijat, Luo Yuwei, Mutellip Imin, Abduqeyum Ablimit, Atikem Rozi and Akbar Imin–were charged with being involved with Uighurbiz during a secret trial held in November 2014, according to Tohti’s lawyer Li Fangping. Many were administrators for the site, according to state media. According to the political prisoner database of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, an organization set up by the U.S. Congress to monitor human rights and laws in China, Rozi and Mutellip Imin wrote for the site. Imin, who is from Xinjiang and enrolled at Istanbul University in Turkey, has a blog, too. He was arrested when he tried to leave China.

According to The New York Times, three of the students made televised confessions on the state-run China Central Television in September, saying they worked for the site. Halmurat claimed to have written an article, Nijat claimed to have taken part in editorial policy decisions, and Luo, from the Yi minority, claimed to have done design work.

The seven students were sentenced to three to eight years in prison, according to the Global Times, a government-affiliated website. The length of sentence for each student was unclear and details of where they are being held were not disclosed.

CPJ was unable to determine the names or contact details of the lawyers representing the students. Liu Xiaoyuan, who is also representing, Tohti, told CPJ he did not have information on the students’ cases.

Tohti is being held at the Xinjiang No. 1 Prison in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, according to Radio Free Asia.

Tohti is a member of the Uyghur PEN Center and an honorary member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center and PEN America. He was awarded the 2016 Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders.

Wang Jianmin, New-Way Monthly, Multiple Face

Wang, publisher of two Chinese-language magazines in Hong Kong–New-Way Monthly and Multiple Face–and Guo Zhongxiao, a reporter for the magazines, were detained by police in the southern city of Shenzhen on May 30, 2014, and accused of operating an illegal publication and suspicion of illegal business operations. Liu Haitao, an editorial assistant at the magazines, was detained on June 17, 2014, on the same accusations.

According to a Hong Kong media report, Wang’s wife was also placed under criminal detention on May 30, 2014, and her house was raided the same day. She was held overnight and released on bail. In April 2015, Wang’s wife published an open letter on the overseas Chinese-language website Boxun calling for the release of her husband.

Oiwan Lam, founder of Inmedia, an independent media outlet promoting free speech, told CPJ that Wang and Guo were known as politically well-connected journalists who frequently reported insider information and speculation on political affairs in China. In an editorial, the Hong Kong- and Taiwan-based newspaper Apple Daily described Wang’s magazines as being “close” to the political factions of former Chinese President Jiang Zemin and former Vice President Zeng Qinghong.

Sham Yee Lan, chairwoman of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, told CPJ that the arrests were part of a wider attempt to suppress the freewheeling publishing industry in Hong Kong.

On July 26, 2016 a Shenzhen court sentenced Wang to five years and three months in prison for illegal business operations, and charges of bribery and bid rigging related to his other businesses in China, according to news reports. Guo was sentenced to two years and three months for illegal business operations. He was released in September 2016 after serving his sentence, according to Hong Kong Free Press, an English-language news website. Liu Haitao was released on probation.

CPJ was unable to determine where Wang is being held.

Lü Gengsong, Freelance

Lü, a freelance writer, was detained on July 7, 2014, and his home was raided by security officers in Hangzhou city, Zhejiang province. He was charged with subversion of state power on August 13, according to Human Rights in China. On June 17, 2016, a Hangzhou court sentenced Lü to 11 years in prison after convicting him of the charge. The court said the conviction was related to articles Lü published on corruption, organized crime, and other topics, according to Radio Free Asia.

During an earlier hearing at a Hangzhou court on September 29, 2015, Lü tried to give a statement. The presiding judge interrupted and prohibited Lü from speaking, claiming the content of the statement endangered state security, according to Radio Free Asia.

Lü reported on the sentencing of rights activists and frequently voiced support for the protection of basic rights. In October 2013, Lü and others wrote an open letter and petition against China’s presence on the United Nations Human Rights Council.

Lü had been jailed before. On February 5, 2008, the Hangzhou Intermediate People’s Court sentenced him to four years in prison and one year’s deprivation of political rights on a charge of inciting subversion of state power. A lower court found him guilty of publishing “subversive essays” on foreign websites, according to the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China, which monitors human rights and the rule of law in the country. Lü was released on August 23, 2011.

Lü lost his teaching position at Zhejiang Higher Professional School of Public Security in 1993 over his support of the pro-democracy movement. In 2000 his book, Corruption in the Communist Party of China, was published by Hong Kong Culture and Arts Studio. In March 2007 his article “China’s Biggest Spy Organization: The Political and Legal Affairs Commission” appeared in Beijing Spring, an overseas democracy magazine.

Lü has lodged an appeal with Zhejiang People’s High Court and was awaiting the court’s verdict as of late 2016, his lawyer, Yan Wenxin, told CPJ. Lü is being held at Hangzhou Detention Center. He has high blood pressure and diabetes, according to Radio Free Asia.

Chen Shuqing, Freelance

Chen, a freelance writer and member of the China Democratic Party and the Independent Chinese PEN Center, was detained on September 11, 2014, in Hangzhou city, Zhejiang province, on suspicion of subversion of state power, and his home was raided by agents from the Hangzhou Public Security Bureau. He had written several articles for the overseas Chinese-language website Boxun about pro-democracy advocates, many of whom are in the hospital or detention.

On June 17, 2016, a Hangzhou court sentenced Chen to 10 years and six months in prison for “subversion of state power.” Chen’s lawyer, Fu Yonggang, told reporters the verdict read, “Chen Shuqing published 14 articles on overseas websites Boxun and Canyu,” and “through aforementioned proclamations, statements and articles, Chen Shuqing attacked and smeared the state power and the socialist system.” Chen lodged an appeal with Zhejiang People’s High Court and was awaiting the court’s verdict as of late 2016, another of his lawyers, Liu Rongsheng, told CPJ.

Chen has been jailed before. He was placed under criminal detention on suspicion of inciting subversion of state power on September 14, 2006. On August 16, 2007, he was sentenced by Hangzhou Intermediate People’s Court to four years in prison and one year’s deprivation of political rights for subversion of state power. After the original verdict was upheld at the appellate court, Chen was jailed at Qiaosi prison in Hangzhou. He was released on September 13, 2010, after serving his term.

Chen is being held at Hangzhou Detention Center, his lawyer, Liu, said.

Wang Jing, 64 Tianwang

Wang, a volunteer journalist for the independent human rights news website 64 Tianwang, was arrested on December 10, 2014, while photographing protesters near the Beijing headquarters of the state-run broadcasting agency China Central Television, according to news reports that cited Huang Qi, founder and editor of the website.

In April 2016, Wang was sentenced to four years and 10 months in prison for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” 64 Tianwang published what it described as a copy of the verdict. It said Wang “caused serious disruptions of online order” by posting “a large amount of information that is unconfirmed and defaming to the work of governmental agencies” in articles for 64 Tianwang and other websites. The court cited articles Wang wrote about protests and reports of Chinese police harassing, detaining, and beating protesters, according to 64 Tianwang.

In March 2014, Wang was detained by Chinese authorities after she and two other volunteer journalists published a report on 64 Tianwang about an attempted self-immolation and the defacing of a portrait in Tiananmen Square, news reports said. On that occasion she was held on suspicion of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” but released on bail about a month later, the reports said. She was not charged at the time.

Wang has a brain tumor and her condition has deteriorated in custody, according to Radio Free Asia. The Hong Kong-based group Chinese Human Rights Defenders, citing her lawyer, reported that she was beaten repeatedly by local police and force-fed after she staged hunger strikes to protest her mistreatment.

Wang is being held at Jilin Women’s Prison in Jilin province. Wang’s mother Sun Yanhua told CPJ that Wang was taken to the prison’s hospital in October 2016. In late 2016, she said that her daughter was still in the hospital. Sun said she is only allowed to visit Wang once a month for 30 minutes.

Drukar Gyal (Druklo), Freelance

Tibetan writer Drukar Gyal, also known as Druklo, was detained on March 19, 2015, according to Radio Free Asia. Gyal’s family discovered that he had been arrested after they reported him missing, according to Radio Free Asia, which cited an unnamed source.

A court in Huangnan prefecture in China’s northwestern Qinghai province sentenced Gyal to three years in prison on February 17, 2016 for inciting separatism and endangering social stability, according to news reports. Gyal was not allowed access to a lawyer during his detention or trial, Amnesty International reported, without citing sources.

On March 16, 2015, police searched Gyal’s room and pointed guns at him when he asked to see a search warrant, according to Amnesty International. The court verdict cited Gyal’s posts on his blog and social media about this incident, his comments about religious freedom, and a repost of a news report about the Dalai Lama as evidence of “inciting separatism.”