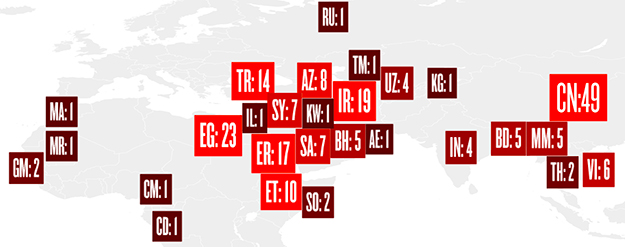

As of December 1, 2015

Analysis: China, Egypt imprison record numbers of journalists

Blog: None jailed in Americas | Blog: Q&A with Vietnam’s Ta Phong Tan

Click on a country name to see summaries of individual cases.

Medium You need to upgrade your Flash Player

|

Charges You need to upgrade your Flash Player

|

Freelance / Staff You need to upgrade your Flash Player

|

Azerbaijan: 8

Nijat Aliyev, Azadxeber

Baku police arrested Aliyev, editor-in-chief of the independent news website Azadxeber, near a subway station in downtown Baku and charged him with possession of illegal drugs. A local court ordered Aliyev to be held in pretrial detention. Authorities have extended his pretrial detention several times.

Colleagues disputed the charges and said they were in retaliation for his journalism. Aliyev’s deputy, Parvin Zeynalov, told local journalists that the outlet’s critical reporting on the government’s religion policies, including perceived anti-Islamic activities, could have prompted the editor’s arrest.

CPJ has documented a pattern in which Azerbaijani authorities file questionable drug charges against journalists whose coverage has been at odds with official views.

Aliyev’s lawyer, Anar Gasimli, told the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, a local press freedom organization, that Aliyev said investigators tortured the journalist in custody and pressured him to admit he had drugs in his possession. The lawyer did not say how Aliyev was tortured. According to the institute, Gasimli said police threatened to plant narcotics in the editor’s apartment and file more serious charges against him.

In January 2013, authorities brought additional charges against Aliyev-illegal import and sale of religious literature, making calls to overturn the constitutional regime, and incitement to ethnic and religious hatred, the institute reported. In March 2013, investigators finished the investigation against the editor, according to local press reports.

On December 9, 2013, the Baku Court for Grave Crimes sentenced Aliyev to 10 years in prison, according to the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel. In June 2014, Azerbaijan’s Court of Appeals denied Aliyev’s appeal, reports said. He was being held in Azerbaijan’s Prison No. 2. CPJ could not determine the state of his health.

In the run-up to the first European Games, held in Baku in June 2015, CPJ and the Sport for Rights coalition pressed the European Olympic Committees to demand the release of imprisoned journalists and a halt to Azerbaijan’s crackdown on journalists and civil society.

Hilal Mamedov, Talyshi Sado

Baku police detained Mamedov, editor of Talyshi Sado (Voice of the Talysh), on June 21, 2012, on allegations that they had found about five grams of heroin in his pocket, the Azeri-language service of the U.S. government-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reported. After his arrest, Baku police declared they found an additional 30 grams of heroin in Mamedov’s home when they searched it the same day, news reports said. A day later, a district court in Baku ordered Mamedov to be held in pretrial detention for three months on drug possession charges. Mamedov’s family claims police planted the drugs, and his colleagues said they believed the editor was targeted in retaliation for his reporting, reports said.

Talyshi Sado covered issues affecting the Talysh ethnic minority group in Azerbaijan. Mamedov’s articles have been published in Talyshi Sado and on regional and Russia-based news websites, according to Emin Huseynov, director of the local press freedom organization Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety. Huseynov told CPJ that Mamedov had investigated the case of Novruzali Mamedov, Talyshi Sado‘s former chief editor who died in prison in 2009. The two journalists were not related.

In July 2012, authorities lodged more charges against Mamedov, including treason and incitement to ethnic and religious hatred, news reports said. Azerbaijan’s interior ministry said in a statement that Mamedov had undermined the country’s security in articles for Talyshi Sado, through interviews with the Iranian broadcaster Sahar TV, and in unnamed books that he was alleged to have translated and distributed. The statement denounced domestic and international protests against Mamedov’s imprisonment and said the journalist used his office to spy for Iran.

In September 2013, Mamedov was sentenced to five years in prison on charges of drug possession, treason, and incitement to ethnic and religious hatred, regional press reported. His trial was marred by procedural violations and authorities failed to back up their charges with credible evidence, news reports said.

Local human rights defenders said they believe the conviction was in retaliation for Mamedov’s criticism of the authorities’ failure to investigate the death of Novruzali Mamedov. News reports said that before his death, the chief editor had been denied adequate medical treatment for several illnesses. Human rights and press freedom groups including CPJ have called for an independent investigation into his death.

According to the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel, the court ruled that Hilal Mamedov was to serve his sentence in a strict penal colony. Mamedov was being held at Prison No. 17, outside Baku, according to an August 2014 report on political prisoners in Azerbaijan by a group of lawyers, human rights defenders, and non-governmental organizations.

In June 2014, Azerbaijan’s Supreme Court denied Mamedov’s appeal, the report said. His lawyers filed an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights, which in November 2014 started the first stages of communication with Azerbaijani authorities, a necessary step before the court can begin work on the case, Kavkazsky Uzel reported. In late 2015 CPJ was unable to determine the status of Mamedov’s case or of his health.

In the run-up to the first European Games, held in Baku in June 2015, CPJ and the Sport for Rights coalition pressed the European Olympic Committees to demand the release of imprisoned journalists and a halt to Azerbaijan’s crackdown on journalists and civil society.

Araz Guliyev, Xeber 44

Guliyev, chief editor of news website Xeber 44, was arrested on hooliganism charges in September 2012 while reporting on a protest in the southeastern city of Masally, news reports said. Residents were protesting over dancers at a festival who they claimed were not properly clothed, the reports said. Police arrested the demonstrators, who were calling on the festival organizers to respect religious traditions.

During Guliyev’s pretrial detention, authorities expanded his charges to include “illegal possession, storage, and transportation of firearms,” “participation in activities that disrupt public order,” “inciting ethnic and religious hatred,” “resisting authority,” and “offensive action against the flag and emblem of Azerbaijan.”

Guliyev’s brother, Azer, told the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel that his brother’s imprisonment could be related to his coverage of protests against an official ban on headscarves and veils in public schools. Xeber 44 covers news about religious life in Azerbaijan and international events in the Islamic world. The journalist’s lawyer told Kavkazsky Uzel that investigators claimed to have found a grenade while searching Guliyev’s home, but his lawyer said the investigators had planted it.

In April 2013, the Lankaran Court on Grave Crimes convicted Guliyev of all charges and sentenced him to eight years in prison.

Guliyev’s lawyer, Fariz Namazli, told the local press freedom organization Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety that the charges against the journalist were not substantiated in court and that the testimony of witnesses conflicted. The lawyer said that Guliyev had been beaten by authorities after his arrest and that he was not immediately granted access to a lawyer.

News reports said that Guliyev filed an appeal, which was denied by regional courts. In July 2014, the Supreme Court of Azerbaijan upheld the journalist’s sentence.

Guliyev was being held at Prison No. 14, outside Baku, according to Kavkazsky Uzel and an August 2014 report on political prisoners in Azerbaijan by a group of lawyers, human rights defenders, and non-governmental organizations. In late 2015, CPJ was unable to determine his health status.

In the run-up to the first European Games, held in Baku in June 2015, CPJ and the Sport for Rights coalition pressed the European Olympic Committees to demand the release of imprisoned journalists and a halt to Azerbaijan’s crackdown on journalists and civil society.

Tofiq Yaqublu, Yeni Musavat

Police arrested Yaqublu, a columnist for the leading opposition daily Yeni Musavat, when he arrived in Ismayilli to interview residents about riots, according to news reports.

On February 4, 2013, the Nasimi District Court in Baku ordered Yaqublu to be held in pretrial detention for two months on charges of organizing mass disorder and violently resisting police. Ilgar Mammadov, an opposition politician who was arrested with Yaqublu, was imprisoned on similar charges, according to news reports. Authorities extended Yaqublu’s pretrial detention several times during the year.

The independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported that the charges against the journalist were in connection with riots in Ismayilli on January 23, 2013. Thousands of residents demonstrated to demand a governor’s resignation after regional authorities refused to shut down a motel that was alleged to have housed a brothel, the U.S. government-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reported. News reports said the motel, which protesters later burned, was said to belong to the family of a high-ranking government official. Authorities sent police to quell the demonstrations and more than 100 residents were detained, the radio station’s Azeri service said.

Rauf Ariforglu, Yeni Musavat‘s chief editor, told Kavkazsky Uzel that his newspaper sent Yaqublu to report on the riots and that the journalist had his press card with him at the time of his arrest. Emin Huseynov, head of the local press freedom organization Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, confirmed that Yaqublu was in the town to report on the unrest, telling CPJ that staff members saw the journalist working there.

On March 17, 2014, a regional court in Ismayilli convicted Yaqublu of mass disorder and sentenced him to five years in prison, according to news reports. His appeal was denied in September 2014. He was being held at Prison No. 13 in late 2014, Kavkazsky Uzel reported.

In April 2015, authorities briefly released Yaqublu to attend the funeral of his 26-year-old daughter, reports said. He returned to prison a week later. CPJ could not determine the details of Yaqublu’s health.

In the run-up to the first European Games, held in Baku in June 2015, CPJ and the Sport for Rights coalition pressed the European Olympic Committees to demand the release of imprisoned journalists and a halt to Azerbaijan’s crackdown on journalists and civil society.

Parviz Hashimli, Moderator, Bizim Yol

Agents with the National Security Agency arrested Hashimli, the editor of the independent news website Moderator and a reporter for the independent newspaper Bizim Yol, outside the offices of the Moderator in Baku. The same day agents claimed to have found a pistol and several grenades after raiding his home without presenting a court order and in the absence of a lawyer, according to news reports.

Agents also raided the newsrooms of the Moderator and Bizim Yol and confiscated equipment, the independent news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported. Both outlets are known for coverage of corruption and human rights abuses as well as for critical reporting on the government of President Ilham Aliyev.

On September 19, 2013, the Sabail District Court in Baku ordered that Hashimli be imprisoned for two months pending an investigation into accusations of smuggling and the illegal possession of weapons, according to news reports. Hashimli denied the allegations.

Emin Huseynov, director of the local press freedom group Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, told CPJ that he believed the charges against Hashimli were fabricated and that his arrest was meant to be a threat to the local press in the run-up to the October 2013 election, which Aliyev later won.

Citing Hashimli’s lawyer, Huseynov told CPJ that agents had orchestrated the detention of the journalist. He said that a man named Tavvakyul Gurbanov had called Hashimli and asked to meet him outside the Moderator offices about a personal matter. When Hashimli got in Gurbanov’s car, agents surrounded the vehicle and searched it. The agents claimed they found six guns and rounds of ammunition. Gurbanov said he brought the weapons along on Hashimli’s request, which the journalist denied, according to news reports. Hashimli denied having met Gurbanov before.

Gurbanov was detained and faced similar charges, news reports said.

In November 2013, Hashimli’s pretrial detention was extended for three months, according to news reports.

On May 15, 2014, the Baku Court of Grave Crimes sentenced Hashimli to eight years in prison, the Azerbaijani service of the U.S. government-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reported. After the Baku Appeals Court denied his appeal in December 2014, his lawyers asked Azerbaijan’s Supreme Court to review the case and acquit the journalist. The court upheld the sentence at a hearing in October 2015, Kavkazsky Uzel reported.

Hashimli was being held at Prison No. 1, outside Baku, according to an August 2014 report on political prisoners in Azerbaijan by a group of lawyers, human rights defenders, and non-governmental organizations. CPJ could not determine the status of Hashimli’s health.

In the run-up to the first European Games, held in Baku in June 2015, CPJ and the Sport for Rights coalition pressed the European Olympic Committees to demand the release of imprisoned journalists and a halt to Azerbaijan’s crackdown on journalists and civil society.

Rauf Mirkadyrov, Zerkalo

Azerbaijan’s National Security Agency detained Mirkadyrov when he arrived in Baku from Ankara, according to regional and international press reports. Mirkadyrov, who worked as the Turkey correspondent for the independent Azerbaijani daily newspaper Zerkalo for three years, had been deported from Turkey the day before at the request of Azerbaijani authorities, the reports said.

Mirkadyrov was arrested and charged with espionage, according to news reports. Mirkadyrov was ordered into pretrial detention for three months, the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported.

In July 2014, authorities extended his detention until November 21 of that year, Kavkazsky Uzel said. When the term was about to expire, the Nasimi District Court ordered Mirkadyrov to be kept in pretrial detention for a five more months, regional press reported.

The espionage charges stemmed from Mirkadyrov’s trips to Armenia and Georgia, as well as his time in Turkey. He was accused of meeting with Armenian security services and handing them information of a political and military nature, including state secrets, the independent news website Contact reported, citing the Azerbaijani prosecutor-general’s office.

Mirkadyrov denied the accusations and said they were politically motivated and in retaliation for his work. If convicted, he could be sentenced to life in prison, Kavkazsky Uzel reported.

While reporting for Zerkalo in Turkey, Mirkadyrov often criticized Turkish and Azerbaijani authorities for human rights abuses, news reports said.

According to a Kavkazsky Uzel report that cited Mirkadyrov’s wife, Turkish police detained the family in Ankara on April 18, 2014, and accused them of being in the country on expired travel documents. She said their documents were valid through the end of the year. Mirkadyrov was deported the next day. His wife later said that the family showed police a document that said the family was allowed to remain in Turkey until the end of the year, the paper reported. Turkish authorities did not explain the discrepancy, the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported.

Mirkadyrov was also involved in nongovernmental projects on improving dialogue between Armenia and Azerbaijan, according to news reports. The two countries have not had diplomatic relations since the early 1990s, due to a dispute over the Nagorno-Karabakh region.

Mirkadyrov is being held at the National Security Agency’s pretrial detention facility, Kavkazsky Uzel reported. In August 2015, authorities briefly hospitalized him after he complained of hypertension, his lawyer told Kavkazsky Uzel. A month later, news reports said that the journalist’s pretrial detention was extended until November 16. A closed-door trial for Mirkadyrov began on November 19, 2015, according to reports.

In the run-up to the first European Games, held in Baku in June 2015, CPJ and the Sport for Rights coalition pressed the European Olympic Committees to demand the release of imprisoned journalists and a halt to Azerbaijan’s crackdown on journalists and civil society.

Seymur Hazi, Azadliq

Police in the eastern Absheron district arrested Hazi, a reporter for the opposition newspaper Azadliq, over claims that he attacked a man at a bus stop, the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported. The day after his arrest, the Absheron District Court ordered the journalist, who also uses the name Haziyev, to be held in pretrial detention for two months, the report said. He was charged with hooliganism.

At the trial in Absheron District Court on November 11, the journalist’s lawyer requested that the judge be disqualified because authorities continued to hold Hazi even though his pretrial detention had expired, Kavkazsky Uzel reported. The judge denied the request.

Authorities said that while waiting for a bus on his way to work, Hazi attacked and beat a Baku resident named Magerram Hasanov, according to Kavkazsky Uzel. Hazi said in court that he had acted in self-defense, Kavkazsky Uzel reported. He said Hasanov had insulted and attacked him. Elton Guliyev, the journalist’s lawyer, told Kavkazsky Uzel that he believed authorities had orchestrated the altercation because police arrived moments after it started. Guliyev said he believed Hazi had been imprisoned in retaliation for his journalism.

Hazi often criticized the Azerbaijani government’s domestic and foreign policies in his reports for Azadliq, according to Kavkazsky Uzel. As a host for Azadliq‘s online TV program “Azerbaijan Saati” (Azerbaijani Hour), he was critical of government corruption and human rights abuses in the country.

In January 2015, Hazi was sentenced to five years in jail, news reports said. His appeal was denied. Hazi is being held at Baku Investigative Prison No. 1. CPJ could not determine details of his health.

In the run-up to the first European Games, held in Baku in June 2015, CPJ and the Sport for Rights coalition pressed the European Olympic Committees to demand the release of imprisoned journalists and a halt to Azerbaijan’s crackdown on journalists and civil society.

Khadija Ismayilova, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

Ismayilova, an award-winning investigative reporter and program host on Radio Azadlyg, the Azeri service of the U.S. government-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, was arrested in Baku on December 5, 2014.

Authorities charged Ismayilova with inciting a man to commit suicide and ordered her to be imprisoned for two months pending an investigation into the case, news reports said. While she was in jail, authorities raided the radio station’s Baku bureau, detained and interrogated its staff, confiscated financial documents and reporting equipment, and sealed the newsroom, reports said.

In January 2015, a Baku court extended Ismayilova’s pretrial detention for another two months; a few weeks later, the general prosecutor’s office brought new charges against her of embezzlement, illegal business, tax evasion, and abuse of power, according to regional and international press reports.

During her trial, defense witnesses, including RFE/RL representatives, denied the accusations against Ismayilova, telling the court that she did not have authority to conduct business deals, make decisions about hiring, or manipulate fiscal documents, news reports said. Additionally, the man whose attempted suicide authorities used to file original charges against Ismayilova stated publicly that prosecutors had forced him to incriminate the journalist, RFE/RL reported.

On September 1, 2015, the Baku Court of Grave Crimes sentenced Ismayilova to seven and a half years in prison on charges of illegal business, tax evasion, abuse of power, and embezzlement, local and international press reported. Authorities dropped the charge of incitement to suicide. On November 25, 2015 the Baku Court of Appeals upheld Ismayilova’s conviction, according to the Sport for Rights coalition.

Ismayilova is known for her exposés of high-level government corruption, including her investigation into alleged ties between President Ilham Aliyev’s family and businesses. For years, Ismayilova also covered Azerbaijan’s grave human rights record.

Ismayilova and her lawyer denied the allegations against her, which they said were in retaliation for her coverage. In an article published by the local press two days before Ismayilova’s arrest, Ramiz Mehdiyev, head of the presidential administration, accused her of treason and espionage, according to news reports.

Before her imprisonment, authorities had consistently harassed Ismayilova through smear campaigns, prosecution, and travel bans, CPJ research shows. Ismayilova, the 2015 winner of the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award, is being held in Prison No. 4, according to the Sport for Rights coalition. CPJ was unable to determine Ismayilova’s health.

In the run-up to the first European Games, held in Baku in June 2015, CPJ and the Sport for Rights coalition pressed the European Olympic Committees to demand the release of imprisoned journalists and a halt to Azerbaijan’s crackdown on journalists and civil society.

Bahrain: 5

Abduljalil Alsingace, Freelance

Alsingace, a journalistic blogger and human rights defender, was among a number of high-profile government critics arrested as the government renewed its crackdown on dissent after pro-reform protests swept the country in February 2011.

In June 2011, a military court sentenced Alsingace to life imprisonment for “plotting to topple the monarchy.” In all, 21 bloggers, human rights activists, and members of the political opposition were found guilty on similar charges and handed lengthy sentences.

On his blog, Al-Faseela (Sapling), Alsingace wrote critically about human rights violations, sectarian discrimination, and repression of the political opposition. He also monitored human rights for the Shia-dominated opposition Haq Movement for Civil Liberties and Democracy. He was first arrested on anti-state conspiracy charges in August 2010 as part of widespread reprisals against political dissidents, but was released in February 2011 as part of a government effort to appease a then-nascent protest movement.

In September 2012, the High Court of Appeal upheld Alsingace’s conviction and life sentence, along with those of his co-defendants. Four months later, on January 7, 2013, the Court of Cassation, the highest court in the country, also upheld the sentences.

In 2015, Alsingace began refusing all solid food to protest the conditions at Jaw Central Prison, where he was being held. In a joint statement on October 7, 2015, the 200th day of his protest, CPJ and other press freedom and human rights organizations called for his release.

In November 2015, Alsingace was temporarily released to allow him to attend his mother’s funeral. As of late 2015, he remains detained in a clinic where he is receiving treatment in relation to his hunger strike.

Ahmed Humaidan, Freelance

Humaidan, a freelance photojournalist, was sentenced to 10 years in prison on March 26, 2014, in a trial of more than 30 individuals charged with participating in a 2012 attack against a police station on the island of Sitra, according to news reports. The reports said three defendants were acquitted, and the rest were given three to 10 years in prison.

Humaidan was at the station to document the attack as part of his coverage of unrest in the country since anti-government protests erupted in February 2011, according to news reports. His photographs were published by local opposition sites, including the online newsmagazine Alhadath and the news website Alrasid.

Adel Marzouk, head of the Bahrain Press Association, an independent media freedom organization based in London, told CPJ that Humaidan’s photographs had exposed police attacks on protesters during demonstrations. Humaidan’s family said authorities had sought his arrest for months and had raided their home five times to try to arrest him, news reports said.

The High Court of Appeals upheld Humaidan’s sentence on August 31, 2014, despite calls by CPJ and other human rights organizations to throw out the conviction.

In 2014, the U.S. National Press Club honored Humaidan with its John Aubuchon Press Freedom Award.

Humaidan is being held in Jaw Central Prison.

Hussein Hubail, Freelance

Hubail, a photographer, was sentenced to five years in prison on April 28, 2014, on charges of inciting protests against public order, according to news reports. Eight other individuals were sentenced in the same trial, including online activist Jassim al-Nuaimi and artist Sadiq al-Shabani, the reports said.

Hubail was arrested at the Bahrain International Airport and held incommunicado for six days before being transferred to the Dry Dock prison on August 5, 2013, the Bahrain Center for Human Rights reported.

The arrest came amid political tension in Bahrain over an opposition protest planned for August 14, 2013, that was modeled after the demonstrations that led to the ouster of Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi. Bahrain King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa decreed new measures to crack down on protesters who the government believed were engaging in terrorist activities.

On August 7, 2013, Hubail was interrogated by the public prosecutor, who accused him of incitement against the regime and calling for illegal gatherings. Hubail’s lawyer, Ali al-Asfoor, said in a series of Twitter posts that investigators had questioned Hubail about his photography and purported posts on social media that had called for the protests on August 14.

Hubail, who photographs opposition protests, has had his work published by Agence France-Presse and other news outlets. In May 2013, the independent newspaper Al-Wasat awarded him a photography prize for his picture of protesters enshrouded in tear gas.

Hubail said he was tortured in custody by the Criminal Investigation Department, according to the Bahrain Center for Human Rights. The center said Hubail told of being beaten, kicked, forced to stand for long periods of time, and deprived of sleep. The Bahraini Information Affairs Authority told CPJ on August 28, 2013, that the government was investigating the torture claims.

The High Court of Appeals upheld Hubail’s conviction on September 21, 2014, according to news reports.

In April 2015, someone familiar with Hubail’s situation, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, told CPJ that Hubail’s health has deteriorated and that he has been denied adequate medical care for his heart condition. The journalist is being held in Jaw Central Prison.

Ali Mearaj, Freelance

Bahraini security forces arrested Mearaj at his home in the village of Nuwaidrat and confiscated his computer and phone, according to news reports. On April 8, 2014, he was sentenced to two and a half years in prison on charges of “insulting the king” and “misusing communication devices” in relation to posts he was accused of writing on the opposition website Lulu Awal, the reports said.

Lulu Awal publishes news and information in opposition to the Bahraini government. The website’s YouTube page has posted hundreds of videos showing peaceful protests and violent clashes between protesters and police. Anti-government protests have been a frequent occurrence in the country since the government cracked down on large-scale demonstrations in 2011.

According to news reports citing court documents, Mearaj said he posted news and pictures of demonstrations on several websites, but he denied insulting the king or being responsible for Lulu Awal. Authorities said that a computer seized from his home had been used to post on Lulu Awal, according to news reports. It was not clear if any specific posts on the website led to the arrest and conviction.

Mearaj’s sentence was under appeal in late 2015 after repeated delays for more than a year. He is being held in Jaw Central Prison.

Sayed Ahmed al-Mosawi, Freelance

Authorities raided al-Mosawi’s home on February 10, 2014, and arrested him along with his brother, Mohammed, according to news reports. The freelance photographer was transferred to Dry Dock jail after being interrogated about his work as a photographer.

Al-Mosawi’s internationally recognized photographs, most of which he posts on social networking sites, have won several awards. His work includes a range of subjects such as wildlife and daily life in Bahrain in addition to opposition protests. Anti-government protests have been a frequent occurrence in Bahrain since the government cracked down on large-scale demonstrations in 2011.

According to the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, the government has frequently abused an overly broad definition of terrorism as a tool to suppress dissent and independent reporting.

The journalist told his family in a phone call from prison in 2014 that he had been beaten and given electric shocks, according to the Bahrain Center for Human Rights.

Al-Mosawi and his brother were charged in late 2014 with rioting and participating in a terror organization, according to news reports. On November 23, 2015, al-Mosawi was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment and had his citizenship revoked, according to news reports. Since 2012, Bahrain has revoked the citizenship of more than 130 Bahrainis, including journalists, human rights defenders and accused terrorists, according to local human rights groups.

Bangladesh: 5

Mahmudur Rahman, Amar Desh

Rahman, 60, acting editor and majority owner of the opposition Bengali-language daily Amar Desh, was arrested at his office on April 11, 2013, according to news reports. Rahman was charged with publishing false and derogatory information that incited religious tension. The government cited what it said was critical coverage of the Shahbagh movement, which calls for the death penalty for Islamist leaders on trial on war crimes charges.

News reports cited a February 2013 article published in Amar Desh as an example of the daily’s critical coverage during heightened political and religious tension. The article, headlined “Bloggers committing contempt of religion and court,” criticized self-described atheist bloggers, who helped amplify support for the Shahbagh movement, and called them “enemies of Islam” and their work “vulgar, objectionable propaganda.”

Rahman was also charged with sedition and unlawful publication in connection with his paper’s reports in December 2012 that questioned the impartiality of a war crimes tribunal set up by the government to investigate mass killings during the war of independence. The paper’s reports included leaked Skype conversations of a judge presiding over the tribunal. The controversy led to the judge’s resignation.

At his initial hearing in late 2013, Rahman refused to request bail in protest, news reports said.

Rahman was also indicted on corruption charges over allegations that he failed to submit his wealth statement despite being served several legal notices. The charges relate to his tenure as energy adviser in the previous Bangladesh Nationalist Party-led government, according to reports. The party, now in opposition, is aligned with Islamist parties.

In August 2015, a Dhaka court sentenced Rahman to three years in prison for not providing details of his wealth, according to news reports. Rahman is facing trial on several other cases. It is unclear if he has been convicted in any of those cases, according to the English-language The Daily Star. CPJ contacted Rahman’s newspaper to try to verify the status of his case, but by late 2015 had not received a response.

Rahman was previously arrested in June 2010 and spent 10 months in prison for contempt of court in connection with Amar Desh reports that accused the country’s courts of bias in favor of the state.

CPJ could not determine details of his health.

Salah Uddin Shoaib Choudhury, Weekly Blitz

A Dhaka court sentenced Choudhury, an editor of the Bangladeshi tabloid Weekly Blitz, to seven years in prison over his articles about the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Bangladesh.

Choudhury was convicted of harming the country’s interests under section 505(A) of the penal code, having been found to have intentionally written distorting and damaging materials, reports said. Choudhury had written about anti-Israeli attitudes in Muslim countries and the spread of Islamist militancy in Bangladesh.

The prosecutor in the case, Shah Alam Talukder, told Agence France-Presse that Choudhury was taken to prison after the verdict. The editor’s family said they would appeal the decision in the High Court, news reports said. No details about his state of health, or where he is being held, have been disclosed.

The sentence was linked to Choudhury’s arrest in November 2003 when he tried to travel to Israel to participate in a conference with the Hebrew Writers Association. Bangladesh has no diplomatic relations with Israel, and it is illegal for Bangladeshi citizens to travel there. Choudhury was released on bail in 2005.

He was charged with passport violations, but the charges were dropped in February 2004 and he was accused of sedition, among other charges, in connection with his articles, according to news reports. The editor was not convicted on the sedition charge, the reports said. He was arrested again in 2012 in connection with embezzlement charges, and the current charges relating to his writing were filed. In Bangladesh, judicial proceedings can take years to resolve. In February 2015, Choudhary was sentenced to four years in prison on the embezzlement charges, according to news reports.

Abdus Salam, Ekushey TV

Kanak Sarwar, Ekushey TV

Salam, the owner of Ekushey TV, and Sarwar, a former senior correspondent for the privately owner broadcaster, have been accused of sedition and being in violation of Bangladesh’s Pornography Act, according to reports. Some journalists said in news reports and to CPJ that the arrests were related to a speech by Tarique Rahman, the son of opposition leader Khaleda Zia, which was broadcast by the channel on January 5, 2015.

Salam was arrested at the station’s offices in Dhaka on January 6, 2015, according to local news reports. At a press conference in Dhaka after his arrest, Information Minister Hasanul Haq Inu said police had charged the chairman of the channel under the Pornography Control Act of 2012. Police said a woman filed a complaint in November 2014 saying she had been vilified in a news program, according to reports. The police said Ekushey TV, which covers local and national news, aired pornographic images of the woman, news reports said. The channel denies the accusations, reports said.

Salam was also charged with sedition, according to news reports. Authorities claim he confessed to being guilty of sedition in a statement before a judge on January 19, 2015, news reports said.

In March 2015, Sarwar was arrested under the Pornography Act after the station’s owner, Salam, was said to have confessed to charges brought against him, reports said. CPJ was unable to determine if Sarwar was formally charged under the act. Sarwar was also charged with sedition, according to news reports. After Sarwar’s arrest, members of the Jatiya Press Club issued a statement expressing concern over the government’s role in undermining independent media in the country, according to reports.

In the speech aired by Ekushey TV on January 5, 2015 Rahman, the senior vice chairman of opposition leader Zia’s party, called for the toppling of the Sheikh Hasina-led government, reports said. Rahman, who has been in exile since 2008 and faces corruption charges in Bangladesh, is a fierce critic of Hasina’s father, the founder of the country.

Sarwar was fired in the days after the speech was aired, reports said. The broadcaster has not commented in English-language reports on the reason for his dismissal.

Ekushey TV was unavailable in some parts of the country after the airing of Rahman’s speech, according to local and international news reports. Cable operators said they were instructed to take Ekushey TV off the air, according to Agence France-Presse. Authorities denied issuing any order, reports said.

Zia, who had been confined to her office earlier in the year after calling on her supporters to topple the Hasina-led government, accused the government of interrupting Ekushey TV broadcasts.

CPJ was unable to determine the state of Salam or Sarwar’s health. The journalists are in jail in Dhaka. Salam was denied bail in January 2015 and March 2015, according to reports. CPJ was unable to determine if a court date has been set for them.

Rimon Rahman, Amader Rajshahi

Rahman, a reporter at the daily Amader Rajshahi, was taken into custody after a complaint was filed against him by members of the paramilitary force Border Guards Bangladesh, according to The Financial Express.

Rahman’s family told CPJ that on September 30, a member of the border guards called Rahman and ordered him to bring his camera, memory card, and mobile phone to a camp in Godagari. At the camp, a guard erased the contacts on his phone and took him to the local police station.

Authorities brought drug-related charges against Rahman, claiming he was in possession of heroin and yaba tablets (a mix of methamphetamine and caffeine), his family and colleagues told CPJ. The family says the allegations are fabricated.

Drug smuggling is rampant along Bangladesh’s border with India and Myanmar, according to news reports.

Rahman’s parents, Raoshan Ara and Al Amin, told CPJ their son had been arrested in retaliation for his critical reporting on the border guards and powerful drug lords operating along the India-Bangladesh border. Rahman had worked as a freelance journalist for various local papers for four years, and most recently worked at the Amader Rajshahi, Ara told CPJ.

On September 15, Rahman published a report alleging that members of the border guards were collecting excessive money from cattle traders at the border with India before the Eid holiday, Ara told CPJ.

Two people familiar with Rahman’s case, who have not been named for security reasons, told CPJ that Rahman had reported on border guards’ alleged role in drug smuggling.

The border guards did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment.

Rahman’s family told CPJ in October 2015 that he is being held at a Rajshahi jail. They reported no health issues, but expressed concern about his mental health. The family told CPJ they had not heard if a date for his trial had been set.

Cameroon: 1

Ahmed Abba, Radio France Internationale

Ahmed Abba, a Nigerian national and correspondent for Radio France Internationale’s (RFI) Hausa service, was arrested by Cameroonian officials in Maroua, the capital of the Far North Region of Cameroon, on July 30, 2015, according to a report by RFI. He was taken to the capital, Yaoundé. The journalist was denied access to his lawyer until October 19, RFI told CPJ.

RFI cited the journalist’s lawyer, Charles Tchoungang, as saying Abba was interrogated in relation to the activities of the extremist sect Boko Haram, which has renamed itself the Islamic State in West Africa. Formed in 2002, Boko Haram, which is based in northern Nigeria, has been increasing its presence in northern Cameroon since 2014, according to reports. The group has become notorious for mass kidnappings and targeted attacks on civilians, reports said.

According to RFI, Abba mostly covered refugee issues in the region. The outlet said that Abba had reported on attacks carried out by Boko Haram, but that he never cited any Boko Haram sources or conducted investigations into Boko Haram activities.

Dennis Nkwebo, president of the Cameroon Journalism Trade Union, told CPJ in September 2015 that Abba has lived in northern Cameroon for some time. He said the day Abba was arrested he had gone to a meeting at the office of a local governor. The reason for Abba’s visit to the governor was not clear.

RFI told CPJ that it had not been told of any specific allegations against Abba. The outlet said that it was not aware that Abba had broken any local laws through his reporting and that it had had no contact with him since his arrest.

Authorities had not disclosed any charges against Abba as of late 2015. RFI said the journalist was healthy and was being held in a prison in Yaoundé.

China: 49

Yang Tongyan (Yang Tianshui), Freelance

Yang, known by his pen name Yang Tianshui, was detained along with a friend in Nanjing, eastern China. He was tried on charges of subverting state power and, on May 17, 2006, the Zhenjiang Intermediate People’s Court sentenced him to 12 years in prison.

Yang was a well-known writer and member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He was a frequent contributor to U.S.-based websites banned in China, including Boxun News and Epoch Times. He often wrote critically about the ruling Communist Party and advocated the release of jailed Internet writers.

According to the verdict in Yang’s case, which was translated into English by the U.S.-based prisoner advocacy group Dui Hua Foundation, the harsh sentence was over a fictitious online election, established by overseas Chinese citizens, for a “democratic Chinese transitional government.” His colleagues said he was elected to the leadership of the fictional government without his prior knowledge. He later wrote an article in Epoch Times in support of the model.

Prosecutors also accused Yang of transferring money from overseas to Wang Wenjiang, a Chinese dissident jailed for endangering state security. Yang’s defense lawyer argued that this money was humanitarian assistance to Wang’s family and should not have constituted a criminal act.

Believing that the proceedings were fundamentally unjust, Yang did not appeal. He had already spent 10 years in prison for his opposition to the military crackdown on demonstrators at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

In June 2008, Shandong provincial authorities refused to renew the law license of Yang’s lawyer, press freedom advocate Li Jianqiang. In 2008, the PEN American Center announced that Yang had received the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award.

Yang’s health deteriorated in 2015. He has pleural tuberculosis, nephritis, diabetes, high blood pressure, and other conditions, according to Radio France Internationale. Because Yang maintains he is innocent, his medical parole applications have been rejected. To demand his right to proper medical care, Yang has staged hunger strikes, according to Radio France Internationale.

Yang is being held in Nanjing No. 1 Prison in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, according to Radio Free Asia.

Qi Chonghuai, Freelance

Tengzhou police arrested Qi, a journalist of 13 years, and charged him with fraud and extortion. He was sentenced to four years in prison on May 13, 2008. The arrest occurred about a week after police detained Qi’s colleague, Ma Shiping, a freelance photographer, on charges of carrying a false press card.

Qi and Ma had criticized a local official in Shandong province in an article published June 8, 2007, on the website of the U.S.-based Epoch Times, according to Qi’s lawyer, Li Xiongbing. On June 14, 2007, the two posted photographs on the Xinhua news agency’s anti-corruption Web forum that showed a luxurious government building in the city of Tengzhou. Ma was sentenced in 2007 to one and a half years in prison. He was released in 2009, according to Jiao.

Qi was accused of taking money from local officials while reporting several stories, a charge he denied. The people from whom he was accused of extorting money were local officials threatened by his reporting, Li said. Qi told his lawyer and his wife, Jiao Xia, that police beat him during questioning on August 13, 2007, and again during a break in his trial.

Qi was due to be released in 2011, but in May of that year local authorities told him the court had received new evidence against him. On June 9, 2011, less than three weeks before the end of his term, a Shandong provincial court sentenced him to an additional eight years in prison, according to the New York-based advocacy group Human Rights in China and Radio Free Asia.

Human Rights in China, citing an online article by defense lawyer Li Xiaoyuan, said the court tried Qi on a new count of stealing advertising revenue from China Security Produce News, a former employer. The journalist’s supporters speculated that the charge was in reprisal for Qi’s statements to his jailers that he would continue reporting after his release, according to The New York Times.

Qi was being held in Tengzhou Prison, a four-hour trip from his family’s home, which limits visits. Jiao told journalists in 2012 that her husband offered her a divorce, but she declined. As of late 2015, no new information about Qi’s legal status or health had been disclosed.

Ekberjan Jamal, Freelance

On two occasions in November 2007, Ekberjan used his cell phone to record sounds of riots in his home town of Turpan. The audio files, which included the noise of rioters, sirens, and a voice-over of Ekberjan describing what was happening, were sent to friends in the Netherlands, and later used in news reports by Radio Free Asia and Phoenix News in Hong Kong. Ekberjan posted links to the news reports on his blog, which was closed by authorities on December 25, 2007, according to the rights group World Uyghur Congress.

In an April 2009 Radio Free Asia report, Ekberjan’s mother said he made the recordings on two occasions, but at his trial he faced 21 counts of sending information abroad. She told Radio Free Asia she believed he might have been motivated to send the files to help achieve his ambition of studying abroad. The Turpan Intermediate People’s Court sentenced him to 10 years in prison on February 28, 2008 for “separatism”-trying to break away from the Communist Party-and revealing state secrets, crimes under articles 103 and 11 of the Chinese penal code.

As of April 2009, he was being held in the Xinjiang Number 4 prison in Urumqi, Radio Free Asia reported. No new information about his health or where he is being held has been disclosed, according to Radio Free Asia.

Liu Xiaobo, Freelance

Liu, a longtime advocate of political reform and the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was imprisoned on charges of inciting subversion through his writing. Liu was an author of Charter 08, a document promoting universal values, human rights, and democratic reform in China, and was among its 300 original signatories. He was detained in Beijing shortly before the charter was officially released, according to international news reports.

Liu was formally charged with subversion in June 2009, and he was tried in the Beijing No. 1 Intermediate Court in December of that year. Diplomats from the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Sweden were denied access to the trial, the BBC reported. On December 25, 2009, the court convicted Liu of inciting subversion and sentenced him to 11 years in prison and two years’ deprivation of political rights.

The verdict cited several articles Liu had posted on overseas websites, including the BBC’s Chinese-language site and the U.S.-based websites Epoch Times and Observe China, all of which had criticized Communist Party rule. Six articles were named, including pieces headlined, “So the Chinese people only deserve ‘one-party participatory democracy?'” and “Changing the regime by changing society,” as evidence that Liu had incited subversion. Liu’s income was generated by his writing, his wife told the court.

The court verdict cited Liu’s authorship and distribution of Charter 08 as further evidence of subversion. The Beijing Municipal High People’s Court upheld the verdict in February 2010.

In October 2010, the Nobel Prize committee awarded Liu its 2010 peace prize “for his long and nonviolent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.” In September 2015, Geir Lundestad, who was secretary of the Norwegian Nobel committee when Liu was awarded the prize, claimed that the Norwegian government tried to dissuade the committee for fear of offending the Chinese government, according to reports. Norway’s foreign minister at the time, Jonas Gahr Støre, denied the allegations.

Liu’s wife, Liu Xia, has been under house arrest in her Beijing apartment since shortly after her husband’s detention, according to international news reports. Authorities said she could request permission to visit Liu every two or three months, the BBC reported.

In March 2013, unidentified assailants beat two Hong Kong journalists when they filmed an activist’s attempt to visit Liu Xia at her home. In February 2014, Liu Xia spent a brief period in the hospital for treatment of heart problems, depression, and other medical conditions. She remained under house arrest in late 2015.

In June 2013, Liu’s brother-in-law, Liu Hui, a manager of a property company, was convicted of fraud in what the journalist’s family said was reprisal for Liu Xiaobo’s journalistic work. The conviction stemmed from a real-estate dispute that Liu Hui’s lawyers said had already been settled. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison, news reports said. A court rejected his appeal in August 2013.

Liu Xiaobo was being held in Jinzhou Prison in northeastern China’s Liaoning province, according to news reports.

In August 2015, Liu’s three brothers visited him for the first time in 13 months. They told reporters at Radio France Internationale that Liu was not allowed to communicate with his family through letters.

Kunchok Tsephel Gopey Tsang, Chomei

Public security officials arrested the online writer Tsang in Gannan, a Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in the south of Gansu province, according to Tibetan rights groups. Tsang ran the Tibetan cultural issues website Chomei, according to the India-based Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy. Kate Saunders, U.K. communications director for the International Campaign for Tibet, told CPJ that she learned of his arrest from two sources.

The detention appeared to be part of a wave of arrests of writers and intellectuals in advance of the 50th anniversary of the March 1959 uprising preceding the Dalai Lama’s departure from Tibet. The 2008 anniversary had provoked ethnic rioting in Tibetan areas, and international reporters were barred from the region.

In November 2009, a Gannan court sentenced Tsang to 15 years in prison for disclosing state secrets, according to The Associated Press.

Tsang served four years of his sentence in Dingxi prison in Lanzhu, Gansu province, before being transferred in August 2013 to another prison in Gansu where conditions are harsher and there are serious concerns for his health, according to PEN International. His family is allowed to visit every two months, and is permitted to speak with him only in Chinese via an intercom and separated by glass screen. Not being allowed to converse in Tibetan is difficult for many of his family members, PEN International said.

As of late 2015 it was unclear in which prison Tsang was being held.

Memetjan Abdulla, Freelance

Abdulla, editor of the state-run China National Radio Uighur service, was detained in July 2009 and accused of instigating ethnic rioting in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region through postings on the Uighur-language website Salkin, which he managed in his spare time, according to international news reports. A court in the regional capital, Urumqi, sentenced him to life imprisonment on April 1, 2010, the reports said. The exact charges against Abdulla were not disclosed.

The U.S. government-funded Radio Free Asia reported on the sentence in December 2010, citing an unnamed witness at the trial. Abdulla was targeted for talking to international journalists in Beijing about the riots and for translating articles on the Salkin website, Radio Free Asia reported. The World Uyghur Congress, a rights group based in Germany, confirmed the sentence with contacts in the region, according to The New York Times.

Abdulla is in an unspecified prison in Xinjiang, according to the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China, which monitors human rights and law in China. CPJ could not determine details of his health in late 2015.

Tursunjan Hezim, Orkhun.

Details of Hezim’s arrest after the 2009 ethnic unrest in northwestern Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region first emerged in March 2011. Police in Xinjiang detained international journalists and severely restricted Internet access for several months after rioting broke out between groups of Han Chinese and the predominantly Muslim Uighur minority on July 5, 2009, in Urumqi, the regional capital.

The U.S. government-funded Radio Free Asia, citing an anonymous source, reported that a court in the region’s far western district of Aksu had sentenced Hezim, along with other journalists and dissidents, in July 2010. Several other Uighur website managers received heavy prison terms for posting articles and discussions about the previous year’s violence, according to CPJ research.

Hezim edited the Uighur website Orkhun. Erkin Sidick, a U.S.-based Uighur scholar, told CPJ that the editor’s whereabouts had been unknown from the time of the rioting until news of the conviction surfaced in 2011. Hezim was sentenced to seven years in prison on undisclosed charges in a trial closed to observers, according to Sidick, who learned the news by telephone from sources in Aksu, the district he comes from. Hezim’s family was informed of the sentence but not of the charges against him, Sidick said. Chinese authorities frequently restrict information on sensitive trials, particularly those involving ethnic minorities, according to CPJ research.

Hezim’s whereabouts in late 2015 were unknown, according to the Uyghur Human Rights Project, a Uighur rights group based in Washington.

Gulmire Imin, Freelance

Imin was one of several administrators of Uighur-language Web forums who were arrested after the July 2009 riots in Urumqi, in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. In August 2010, Imin was sentenced to life in prison on charges of separatism, leaking state secrets, and organizing an illegal demonstration, a witness to her trial told the U.S. government-funded broadcaster Radio Free Asia.

Imin held a local government post in Urumqi. She contributed poetry and short stories to the cultural website Salkin, and had been invited to moderate the site in late spring 2009, her husband, Behtiyar Omer, told CPJ. Omer confirmed the date of his wife’s initial detention in a statement at the Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy in 2011.

Authorities accused Imin of being an organizer of demonstrations on July 5, 2009, and of using the Uighur-language website to distribute information about the event, Radio Free Asia reported. Imin had been critical of the government in her online writing, readers of the website told Radio Free Asia. The website was shut down after the riots and its contents were deleted.

Imin was also accused of leaking state secrets by phone to her husband, who lives in Norway. Her husband told CPJ that he called her on July 5, 2009, but only to check on whether she was safe.

The riots, which began as a protest over the death of Uighur migrant workers in Guangdong province, turned violent and resulted in the deaths of 200 people, according to the official Chinese government count. Chinese authorities blocked access to the Internet in Xinjiang for months after the riots, and hundreds of protesters were arrested, according to international human rights organizations and local and international media reports.

Imin was being held in the Xinjiang women’s prison (Xinjiang No. 2 Prison) in Urumqi, according to the rights group World Uyghur Congress. CPJ could not determine details of her health in late 2015.

Niyaz Kahar, Golden Tarim

Kahar, a reporter and blogger, disappeared during ethnic rioting in Urumqi in July 2009. His family announced in February 2014 that he had been convicted of separatism and was being held in Shikho prison outside Shikho city in the far north of Xinjiang, according to the Uighur service of the U.S.-funded Radio Free Asia.

Kahar worked as a local reporter before launching the Uighur-language website Golden Tarim, which featured articles on Uighur history, culture, politics, and social life.

With the unrest surrounding the riots, it is difficult to determine the exact date of his arrest or where he was initially held. His family had questioned police and government authorities after his disappearance, but received no information, and assumed he had been killed until they were informed of his conviction in 2010, Radio Free Asia reported.

The family was told that Kahar was sentenced to 13 years in prison during a closed court session in Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, though they did not know the date of the trial. Kahar’s sister Nurgul told Radio Free Asia that during their search for Kahar, the family was told by court officials in Urumqi that he “published illegal news and propagated ideas of ethnic separatism on his website. He was charged with the crime of splitting the nation.”

According to a September 2015 report by Radio Free Asia, Kahar’s health is failing. His family is allowed only a 15-minute visit with the journalist every four months. “He is losing his courage year by year,” Radio Free Asia cited his mother as saying.

Thousands of Uighurs remain unaccounted for in Xinjiang. Many were detained during the 2009 crackdown or other security sweeps by Chinese authorities.

Nijat Azat, Shabnam

Authorities imprisoned Azat and another journalist, Nureli Obul, in an apparent crackdown on managers of Uighur-language websites. Azat was sentenced to 10 years in prison and Obul to three years on charges of endangering state security, according to international news reports. The Uyghur American Association reported that the pair were sentenced in July 2010.

Their websites, which have been shut down by the government, published news articles and discussion groups on Uighur issues. The New York Times cited friends and relatives of the journalists who said they were prosecuted because they failed to respond quickly enough when they were ordered to delete content that discussed the difficulties of life in Xinjiang.

The Uyghur PEN Center confirmed to CPJ that Obul was released after completing his sentence. Azat’s whereabouts were unknown as of October 2015. As is the case with many Uighur prisoners, the government releases little information on where they are being held.

Gheyrat Niyaz (Hailaite Niyazi,) Uighurbiz

Security officials arrested Niyaz, a website manager who is sometimes referred to as Hailaite Niyazi, in his home in the regional capital, Urumqi, according to international news reports. He was convicted of endangering state security and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

According to reports, Niyaz was punished because of an August 2, 2009, interview with Yazhou Zhoukan (Asia Weekly), a Chinese-language magazine based in Hong Kong. In the interview, Niyaz said authorities had not taken steps to prevent violence before ethnic unrest in July 2009 in China’s far-western Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region.

Niyaz, who once worked for the state newspapers Xinjiang Legal News and Xinjiang Economic Daily, managed and edited the website Uighurbiz until June 2009. A statement posted on the website quoted Niyaz’s wife as saying that though he had given interviews to international media, he had no malicious intentions.

Authorities blamed local and international Uighur sites for fueling the violence between Uighurs and Han Chinese in the predominantly Muslim Xinjiang region.

According to Humanitarian China, a San Francisco-based Chinese human rights organization, as of late 2015 Niyaz was being held in Changji prison in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. The state of his health and the conditions under which he was being held were unknown.

Liu Xianbin, Freelance

A court in western Sichuan province sentenced Liu to 10 years in prison on charges of inciting subversion through articles published on overseas websites between April 2009 and February 2010, according to international news reports. One article was titled “Constitutional Democracy for China: Escaping Eastern Autocracy,” according to the BBC.

Liu also signed Liu Xiaobo’s pro-democracy Charter 08 petition. (Liu Xiaobo, who won the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize for his actions, is serving an 11-year term on the same charge.)

Police detained Liu Xianbin on June 28, 2010, according to the U.S.-based prisoner rights group Laogai Research Foundation. He was sentenced in 2011 during a crackdown on bloggers and activists who sought to organize demonstrations inspired by uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa, according to CPJ research.

Liu spent more than two years in prison for involvement in the 1989 anti-government protests in Tiananmen Square. He later served 10 years of a 13-year sentence handed down in 1999 after he founded a branch of the China Democracy Party, according to The New York Times.

Liu is being held at Chuanzhong prison in Sichuan province, according to China Change, a website tracking human rights in the country.

Li Tie, Freelance

Police in Wuhan, Hubei province, detained Li, a 52-year-old freelancer, in September 2010, according to international news reports. The Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court tried him behind closed doors on April 18, 2011, but did not announce the verdict until January 18, 2012, when he was handed a 10-year prison term and three additional years’ political deprivation, according to news reports citing his lawyer. Only Li’s mother and daughter were allowed to attend the trial, news reports said.

The court cited 13 of Li’s online articles to support the charge of subversion of state power, a more serious count than inciting subversion, which is a common criminal charge used against jailed journalists in China, according to CPJ research. Evidence in the trial cited articles including one headlined “Human beings’ heaven is human dignity,” in which Li urged respect for ordinary citizens and called for democracy and political reform, according to international news reports. Prosecutors argued that the articles proved Li had “anti-government thoughts” that would ultimately lead to “anti-government actions,” according to the Hong Kong-based Chinese Human Rights Defenders.

Jian Guanghong, a lawyer hired by his family, was detained before the trial and a government-appointed lawyer represented Li instead, according to the group. Prosecutors also cited Li’s membership in a small opposition group, the China Social Democracy Party, the group reported.

Li is in Edong prison in Huanggang, Hubei province, according to Boxun News.

Jin Andi, Freelance

Beijing police detained Jin, a freelance writer, Lü Jiaping, a military scholar, and Lü’s wife, Yu Junyi, on allegations of inciting subversion in 13 online articles they wrote and distributed together, according to international news reports and human rights groups.

A Beijing court sentenced Lü to 10 years in prison and Jin to eight years in prison on May 13, 2011 for subverting state power, according to the Hong Kong-based advocacy group Chinese Human Rights Defenders. Yu, 71, was given a suspended three-year sentence and kept under residential surveillance, which was lifted in February 2012, according to the group and the English-language, Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post and the U.S. government-funded Voice of America. Lü, who is in his 70s, was granted medical parole in February 2015 due to his deteriorating health, according to BBC Chinese.

The court maintains that the three defendants “wrote essays of an inciting nature” and “distributed them through the mail, emails, and by posting them on individuals’ Web pages. [They] subsequently were posted and viewed by others on websites such as Boxun News and New Century News,” according to a 2012 translation of the appeal verdict published online by William Farris, a lawyer in Beijing. The 13 offending articles, which were principally written by Lü, were listed in the appeal judgment, along with dates, places of publication, and the number of times they were reposted. One 70-word paragraph was reproduced as proof of incitement to subvert the state. The paragraph said in part that the Chinese Communist Party’s status as a “governing power and leadership utility has long since been smashed and subverted by the powers that hold the Party at gunpoint.”

Jin is serving his sentence in Xian Prison in Shaanxi province, according to China Political Prisoner Concern, a human rights website based in New York.

Chen Wei, Freelance

Police in Suining, Sichuan province, detained Chen alongside dozens of lawyers, writers, and activists who were jailed nationwide after anonymous online calls for a nonviolent “Jasmine Revolution” in China, according to international news reports. The Hong Kong-based group Chinese Human Rights Defenders reported that Chen was formally charged on March 28, 2011, with inciting subversion of state power.

Chen’s lawyer, Zheng Jianwei, made repeated attempts to visit him but was not allowed access until September 8, 2011, according to the rights group and the U.S. government-funded broadcaster Radio Free Asia. Radio Free Asia reported that police had selected four pro-democracy articles Chen had written for overseas websites as the basis for criminal prosecution.

In December 2011, a court in Suining sentenced Chen to nine years in prison on charges of “inciting subversion.”

Chen has been jailed twice before. He served a year and a half in prison for participating in the Tiananmen protests in 1989. In 1992 he was sentenced to five years in prison for organizing the Chinese Freedom and Democracy Party.

He is being held in Jialin prison in Sichuan province, according to Boxun News.

Gartse Jigme, Freelance

Police arrested Jigme, a Tibetan author and monk, at the Rebgong Gartse monastery in the Malho prefecture of Qinghai province, according to news reports. His family was unaware of his whereabouts until a Qinghai court sentenced him to five years in prison on May 14, 2013. The charges have not been disclosed officially, but the Independent Chinese PEN Center says he was accused of separatism.

The conviction was in connection with the second volume of Jigme’s book, Tsenpoi Nyingtob (The Warrior’s Courage), according to Voice of America and Radio Free Asia. The book contained chapters expressing Jigme’s opinions on topics such as Chinese policies in Tibet, self-immolation, minority rights, and the Dalai Lama, according to news reports.

Jigme was briefly detained in 2011 in connection with the first volume of his book, according to the Hong Kong-based group Chinese Human Rights Defenders and Tibetan rights groups. He had written the book as a reflection on widespread protests in Tibetan areas in the spring of 2008, Tibetan scholar Robert Barnett told CPJ. China has jailed scores of Tibetan writers, artists, and educators for asserting Tibetan national identity and civil rights since the protests.

Authorities did not disclose any information on Jigme’s health or whereabouts. According to the Independent Chinese PEN Center, he may be in prison in Xining, a city in Qinghai province. In late 2015, CPJ was unable to verify his whereabouts or details of his health.

Liu Wei’an, Freelance

Hu Yazhu, Nanfang Daily

The Shaoguan People’s Procuratorate, a state legal body, issued a statement in June 2013 that said Hu and Liu had been arrested in Guangdong province after confessing to accepting bribes while covering events in the northern city of Shaoguan.

Hu and Liu were sentenced to 13 years and 14 years in prison respectively in June 2014 for accepting bribes and for extortion, according to Shaoguan Daily, a government-run newspaper.

Hu, a staff reporter for the official Guangdong Communist Party newspaper Nanfang Daily, and Liu, a freelance writer, had both written articles published in 2011 in Nanfang Daily and on news websites about a dispute involving the illegal extraction of rare minerals in Shaoguan, according to news reports.

The prosecutors’ statement said Hu and Liu accepted 493,000 yuan (about US$82,200) in bribes. The pair were stripped of their press cards and banned from journalism for life, according to the state-run paper China Daily.

Users on Weibo, China’s microblog service, said they suspected the reporters’ arrests were in retaliation for their reports that exposed problems in the government and judiciary.

Shaoguan authorities had not disclosed the health or whereabouts of the journalists in late 2015.

Dong Rubin, Freelance

Dong was detained in Kunming city, Yunnan province, on accusations of misstating his company’s registered assets, according to statements from his lawyer. On July 23, 2014, he was sentenced by Wuhua Court in Kunming to six years and six months in prison on charges of illegal business activity and creating a disturbance, according to the Hong Kong-based group Chinese Human Rights Defenders.

Dong, who runs an Internet consulting company, had used the name “Bianmin” on his microblog to criticize authorities and raise concerns about local issues. He also used the microblog to campaign in 2009 for an investigation into the death of a young man in police custody. Authorities had initially said the man’s death was an accident but later admitted he had been beaten to death, according to news reports. In 2013, Dong raised safety and environmental concerns about a state-owned oil refinery planned near the city of Kunming and expressed support on his microblog for a protest against the project by Kunming residents in May 2013.

Dong predicted his arrest when he wrote on his microblog, which had about 50,000 followers, that strangers had raided his office in late August and taken three computers. “What crime will they bring against me?” Dong wrote. “Prostituting, gambling, using and selling drugs, evading tax, causing trouble on purpose, fabricating rumors, running a mafia online?”

Dong’s friend, Zheng Xiejian, told Reuters in September 2013, “If they want to punish you, they can always find an excuse. They could not find any wrongdoing against Dong and had to settle on this obscure charge.”

Although Dong is not a professional journalist, CPJ determined that he was jailed in connection with his news-based commentary published on the Internet. From August 2013, authorities detained scores of people in a stepped-up campaign to banish online commentary that, among other issues, casts the government in a critical light, according to Chinese media and human rights groups. Many were released, but some were still being held.

During his trial Dong said he was interrogated for seven to eight hours at a time for more than 70 days, while chained to a chair, according to Chinese Human Rights Defenders. He is in frail condition, the Hong Kong-based group stated.

No information on where Dong is being held had been disclosed as of late 2015.

Yao Wentian (Yiu Man-tin), Morning Bell Press

Yao Wentian, a Hong Kong publisher and honorary member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center, was placed under residential surveillance in Shenzhen, in China’s southern Guangdong province, by state public security officers on October 27, 2013, on “suspicion of smuggling ordinary goods” before he was detained on November 2 and formally arrested on November 12, 2013. Yao’s son, Edmond Yao, said his father had been preparing to publish a book titled Chinese Godfather Xi Jinping by the exiled, U.S.-based Chinese author Yu Jie. A previous book by Yu that Yao published, which criticized former Premier Wen Jiabao, is banned in China.

Yao was accused of falsely labeling and smuggling industrial chemicals. His family claimed he was delivering industrial paint to a friend in Shenzhen. At his trial, prosecutors said the cost of the industrial chemicals Yao was accused of smuggling from Hong Kong amounted to more than 1 million yuan (U.S.$163,000), according to reports.

On May 7, 2014 during a closed-door trial at the Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court, Yao was sentenced to the maximum 10 years in prison. According to family members, he is being held in Dongguan prison in Shilong in Guangdong province. The elderly Yao’s health is poor, the family says, because he is forced to do hard labor and is not receiving medical treatment.

Yao started his publishing business, Morning Bell Press, in Hong Kong in the 1990s. The small business has published many books by Chinese dissident writers.

Ilham Tohti, Uighurbiz

Perhat Halmurat, Uighurbiz

Shohret Nijat, Uighurbiz

Luo Yuwei, Uighurbiz

Mutellip Imin, Uighurbiz

Abduqeyum Ablimit, Uighurbiz

Atikem Rozi, Uighurbiz

Akbar Imin, Uighurbiz

Tohti, a Uighur scholar, writer, and blogger, was taken from his home by police on January 15, 2014, and the Uighurbiz website he founded, also known as UighurOnline, was closed. The site, which Tohti started in 2006, was published in Chinese and Uighur, and focused on social issues.

Tohti was charged with separatism by Urumqi police on February 20, 2014. He was accused of using his position as a lecturer at Minzu University of China to spread separatist ideas through Uighurbiz. On September 23, 2014, at the Urumqi Intermediate People’s Court, Tohti was sentenced to life imprisonment. He denied the charges.

Several foreign governments and human rights organizations protested the sentence. The European Union released a statement condemning the life sentence as unjustified. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said the U.S. was concerned by the sentencing and called on Chinese authorities to release him, along with seven of his students.

Tohti’s appeal request was rejected at a hearing in a Xinjiang detention center on November 21, 2014, that was scheduled at such short notice that his lawyer was unable to attend. According to Tohti’s lawyer, Liu Xiaoyuan, the blogger’s mother and brother visited him in jail on October 15, 2015. Tohti said he would appeal the case again, the lawyer told Radio Free Asia.

Seven of his students-Perhat Halmurat, Shohret Nijat, Luo Yuwei, Mutellip Imin, Abduqeyum Ablimit, Atikem Rozi and Akbar Imin-were charged with being involved with Uighurbiz during a secret trial held in November 2014, according to Tohti’s lawyer Li Fangping. Many were administrators for the site, according to state media. According to the political prisoner database of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, an organization set up by Congress to monitor human rights and laws in China, Rozi and Mutellip Imin wrote for the site. Imin, who is from Xinjiang and enrolled at Istanbul University in Turkey, has a blog, too. He was arrested when he tried to leave China.

According to The New York Times, three of the students made televised confessions on the state-run China Central Television in September, saying they worked for the site. Halmurat claimed to have written an article, Nijat claimed to have taken part in editorial policy decisions, and Luo, from the Yi minority, claimed to have done design work.

The seven students were sentenced to three to eight years in prison, according to the Global Times, a government-affiliated website. The length of sentence for each student was unclear and details of where they are being held have not been disclosed.

Tohti was being held at the Xinjiang No. 1 Prison in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, according to Radio Free Asia. Tohti’s family has been allowed to visit him only three times since September 2014.

Tohti is a member of the Uyghur PEN Center and an honorary member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center and PEN America.

Guo Zhongxiao, New-Way Monthly and Multiple Face

Wang Jianmin, New-Way Monthly and Multiple Face

Liu Haitao, New-Way Monthly, Multiple Face

Wang, publisher of two Chinese-language magazines in Hong Kong-New-Way Monthly and Multiple Face-and Guo, a reporter for the magazines, were detained by police in the southern city of Shenzhen on May 30, 2014, and accused of operating an illegal publication and suspicion of illegal business operations. Liu Haitao, an editorial assistant at the magazines, was detained on June 17, 2014, on the same accusations. Liu did not appear on CPJ’s 2014 prison census because the organization was unaware of his arrest.

According to a Hong Kong media report, Wang’s wife was also placed under criminal detention on May 30, 2014, and her house was raided the same day. She was held overnight and released on bail. In April 2015, Wang’s wife published an open letter on the overseas Chinese-language website Boxun calling for the release of her husband.

Oiwan Lam, founder of Inmedia, an independent media outlet promoting free speech, told CPJ that Wang and Guo were known as politically well-connected journalists who frequently reported insider information and speculation on political affairs in China. In an editorial, the Hong Kong- and Taiwan-based newspaper Apple Daily described Wang’s magazines as being “close” to the political factions of former Chinese President Jiang Zemin and former Vice President Zeng Qinghong.