Long before Anya Politkovskaya was slain, her newspaper suffered devastating losses. Yet Novaya Gazeta pushes ahead, investigating corruption, abuse and the deaths of its own reporters.

| MOSCOW Posted May 22, 2007 Vyacheslav Izmailov, Novaya Gazeta‘s military correspondent, leads a visitor down a long, dark hallway to Anna Politkovskaya’s locked office. Things are mostly as she left them, he says, pointing to a desk covered in newspapers and folders. A delicate vase is filled with fresh flowers. At Novaya Gazeta, Moscow’s twice-weekly independent newspaper, the staff’s pain is fresh even now, months after an assassin gunned down Politkovskaya–Anya, as colleagues called her–in her Moscow apartment building in October 2006.

The news staff of 60 can boast of coverage that has spurred more than 30 criminal investigations over the years. Politkovskaya’s work alone resulted in 15 such cases and more than 20 convictions. Now, staffers are turning their attention to the deaths of their own colleagues. “The truth is, we cannot back down,” says Izmailov, whose office is brimming with files on the journalists’ murders. “It is they who must fear us, not vice versa. Only then do we stand a chance at uncovering the truth.” While the paper has made progress in probing all three cases, he says the biggest challenge is getting authorities to prosecute. “We have to make sure our cases are solid so prosecutors would have no choice but to consider them,” Izmailov says. In July 2000, Novaya reporter and special projects editor Igor Domnikov, 42, died in a hospital bed, two months after sustaining severe head injuries in an attack. Five suspects are now on trial for his murder in Kazan, the capital of the Russian republic of Tatarstan, but the suspected masterminds walk free. Domnikov published articles critical of a regional governor before his death. Izmailov, who is investigating the case for the paper, says Novaya is gathering evidence to convince prosecutors to open a separate criminal probe into the suspected masterminds. If Novaya succeeds, Domnikov’s case would be the first in Russia in more than a decade in which both killers and masterminds were brought to justice for killing a journalist.

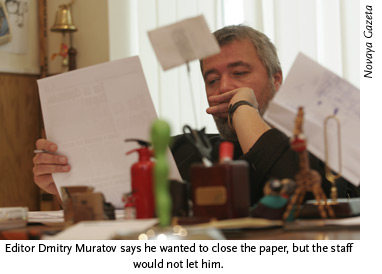

Shchekochikhin, 53, had long covered sensitive subjects such as military corruption and alleged atrocities by Russian troops in Chechnya. In July 2003, he fell gravely ill with what authorities said was “a rare allergy” and died in a hospital only a few days later. Hospital authorities sealed his records, saying only that they were “a medical secret,” and refused to grant access–even to his immediate family. Both Novaya and Shchekochikhin’s relatives suspect he was poisoned to prevent him from further covering an intricate scheme involving money laundering, weapons trafficking, and illegal oil smuggling–allegations that reached into the prosecutor general’s office and the Federal Security Services (FSB). A month before the mysterious sickness claimed his life, Shchekochikhin questioned the independence of the judicial system handling the case. “Do not tell me fairy tales about the independence of judges,” he wrote. “Until we have a fair trial, documents will be purged, witnesses intimidated or killed, and investigators themselves prosecuted.” The prosecutor general’s office says there is no evidence of foul play in Shchekochikhin’s death. At the same time, Novaya is investigating the latest murder of a staffer. In an editorial published immediately after Politkovskaya’s assassination, the staff pledged, “While there is a Novaya Gazeta, her killers won’t sleep soundly.” Four days later, they published Politkovskaya’s unfinished article about torture committed against Chechen civilians by security units loyal to Ramzan Kadyrov, then prime minister and now acting president of the southern republic, along with photos of the torture victims. And in early January, Novaya investigative reporter Igor Korolkov published a lengthy article that blamed security agents for killing government critics as a matter of “state interest.” “When Anya was killed, I called an emergency editorial meeting and wanted to close down the paper,” Editor Dmitry Muratov says. “I told my staff no story is worth dying for. But they wouldn’t let me do it …We had to go on.”

At least two Novaya journalists have received death threats in connection with their investigation of Politkovskaya’s murder. One received an anonymous text message that noted his home address and warned him to stop digging into the case. Editor Muratov says a personal guard has been assigned to one staffer, whom he declined to name. The paper has come a long way. In 1993, five years after leaving the popular daily Komsomolskaya Pravda, Muratov and Sokolov joined with 50 colleagues to start Novaya Gazeta (fittingly, in English, the New Newspaper). The Novaya Web site, which devotes a section to the newspaper’s history, says its founders wanted to create an “honest, independent, and rich” publication that would reach one million readers and influence national policy. It was a lofty goal considering they began with two computers, one printer, two rooms, and no money for salaries. Sokolov and several colleagues handed out copies of Novaya’s first issue to passersby near the Pushkinskaya subway station in central Moscow. It was April 1, 1993–April Fools’ Day, the skeptics pointed out. “We had to work without salaries and publish each issue as if it were our last,” Sokolov says. An initial boost came from former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, who donated part of his 1990 Nobel Peace Prize award to pay for computers and salaries. In 1994, former first lady Raisa Gorbachev bought Muratov his first mobile phone, according to press reports. By 1996, Novaya’s circulation had risen to 70,000 from its initial run of 10,000 copies. There were bumps along the way, though. The paper was never popular with advertisers, who preferred higher-circulation, more commercial publications. It struggled financially and briefly shut down in 1995. In 2002, a series of libel lawsuits carrying hefty fines almost caused another suspension. Muratov says the paper was targeted by disgruntled officials who were accommodated in politicized Russian courts. Unlike most other liberal media, Novaya did not compromise its independent stance in the early 1990s, even when the paper’s position was unpopular. When then-President Boris Yeltsin ordered a violent crackdown on communist hardliners who rose against him in October 1993, Novaya condemned his actions, which left scores of people dead, including six journalists, according to CPJ research. And in 1996, when liberal media backed Yeltsin’s re-election, the paper kept its balanced coverage. That kind of editorial integrity preserved Novaya’s credibility, sustained its readership, and attracted some of Russia’s top journalists. The paper’s independence has been boosted by the fact that, until recently, Novaya journalists owned 100 percent of its stock. In June 2006, to secure an infusion of capital, Muratov persuaded his staff to sell 49 percent of their stock to longtime benefactor Gorbachev and a partner, Aleksandr Lebedev. Lebedev, a billionaire Moscow banker and member of the ruling, pro-Kremlin party United Russia, bought 39 percent of the shares while Gorbachev received 10 percent. Though Lebedev has assured the staff he shares their values and won’t seek to influence editorial matters, there are skeptics in and out of the newsroom. A number of government-connected businesspeople have bought into media properties in recent years. Less than two months after Lebedev’s partial purchase of Novaya, the Kremlin-friendly businessman Alisher Usmanov, general director of Gazprom subsidiary Gazprominvestholding, bought the business daily Kommersant, one of the last independent newspapers with national reach. Two years before, the popular independent daily Izvestiya was purchased by Gazprom; it no longer criticizes the Kremlin. Muratov says he is not worried. Support from Gorbachev and Lebedev, he says, would only strengthen the paper. “I am sure that with his authority, Mr. Gorbachev wants to protect us from all possible forms of pressure,” he told Russian papers. “We want this newspaper to serve not the state, but society.” According to news reports, Lebedev will invest US$3.6 million to raise staff salaries, upgrade the paper’s offices and equipment, and turn Novaya into a daily with a national reach. (It now has a circulation of 171,000, about 40 percent of which is based in Moscow.) When Politkovskaya was murdered, Lebedev immediately announced a reward of US$1 million for information about the killers. The financial backing will no doubt keep Novaya reporters working. But being a muckraking reporter in Russia, the world’s third-most dangerous country for journalists, is a risky proposition. The public overwhelmingly approves of President Vladimir Putin’s policies, and it appears unmoved by attacks on the press, Muratov acknowledges, so every assignment begs the question, “Is the story worth the risk?”

Muratov says Novaya’s staff has pulled together, again, after a colleague’s murder. “We are putting together a team of four journalists to take her place,” he says, then pauses. “It takes four people to replace one Anya.” Nina Ognianova, CPJ’s program coordinator for Europe and Central Asia, led a delegation to Moscow in January 2007. |

In a country where 80 percent of the public gets its news from state-controlled television, Novaya’s dogged coverage of social and political issues has won it devoted readers and passionate enemies. Two of its top journalists have been assassinated and a third has died under mysterious circumstances in the past six years; all reported on risky topics before their deaths. In the face of such peril, it would have been natural for the paper to tone down its tough coverage. But resilience has long been a trademark of Novaya, known by many these days as “Anya’s paper.”

In a country where 80 percent of the public gets its news from state-controlled television, Novaya’s dogged coverage of social and political issues has won it devoted readers and passionate enemies. Two of its top journalists have been assassinated and a third has died under mysterious circumstances in the past six years; all reported on risky topics before their deaths. In the face of such peril, it would have been natural for the paper to tone down its tough coverage. But resilience has long been a trademark of Novaya, known by many these days as “Anya’s paper.” Persuading prosecutors to investigate the mysterious death of Deputy Editor Yuri Shchekochikhin has been more challenging. “We recently received yet another denial from the prosecutor general’s office to our appeal,” Izmailov says.

Persuading prosecutors to investigate the mysterious death of Deputy Editor Yuri Shchekochikhin has been more challenging. “We recently received yet another denial from the prosecutor general’s office to our appeal,” Izmailov says. Novaya Deputy Editor Sergei Sokolov, a tall, thin man with an energetic manner, works long hours investigating Politkovskaya’s murder, as well as other Russian journalist murders. In Novaya, he has pressed authorities to report publicly where they are holding the convicted killer of Sovetskaya Kalmykiya Segodnya Editor Larisa Yudina, slain in June 1998 in the southern Russian republic of Kalmykiya. “Neither the prosecutor’s office nor the justice ministry would answer a simple question for us: Where is the culprit being held? They tell us they have him. So where is he?” he asks.

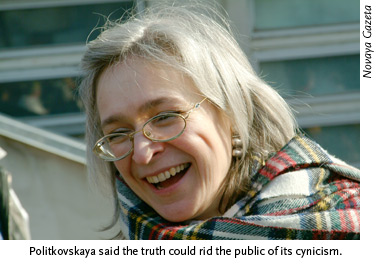

Novaya Deputy Editor Sergei Sokolov, a tall, thin man with an energetic manner, works long hours investigating Politkovskaya’s murder, as well as other Russian journalist murders. In Novaya, he has pressed authorities to report publicly where they are holding the convicted killer of Sovetskaya Kalmykiya Segodnya Editor Larisa Yudina, slain in June 1998 in the southern Russian republic of Kalmykiya. “Neither the prosecutor’s office nor the justice ministry would answer a simple question for us: Where is the culprit being held? They tell us they have him. So where is he?” he asks. Politkovskaya, who seemed energized by public apathy, addressed this in the prologue to her 2002 book, A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya: “People call the newspaper and send letters with one and the same question: ‘Why are you writing about this? Why are you scaring us? Why do we need to know this?’ I’m sure this has to be done, for one simple reason: As contemporaries of this war, we will be held responsible for it. The classic Soviet excuse of not being there and not taking part in anything personally won’t work. So I want you to know the truth. Then you’ll be free of cynicism.”

Politkovskaya, who seemed energized by public apathy, addressed this in the prologue to her 2002 book, A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya: “People call the newspaper and send letters with one and the same question: ‘Why are you writing about this? Why are you scaring us? Why do we need to know this?’ I’m sure this has to be done, for one simple reason: As contemporaries of this war, we will be held responsible for it. The classic Soviet excuse of not being there and not taking part in anything personally won’t work. So I want you to know the truth. Then you’ll be free of cynicism.”