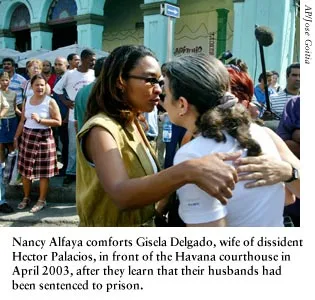

For the crime of reporting the news, Jorge Olivera Castillo spent most of two years in the hellish conditions of Cuba’s prisons. The director of a small independent news agency, the Havana Press, Olivera Castillo was one of 29 journalists arrested in a massive government crackdown on dissidents and the independent media in March 2003. He was convicted in a one-day, closed-door proceeding under a law prohibiting acts “aimed at subverting the internal order of the nation and destroying its political, economic, and social system.” For the crime of reporting the news, Jorge Olivera Castillo spent most of two years in the hellish conditions of Cuba’s prisons. The director of a small independent news agency, the Havana Press, Olivera Castillo was one of 29 journalists arrested in a massive government crackdown on dissidents and the independent media in March 2003. He was convicted in a one-day, closed-door proceeding under a law prohibiting acts “aimed at subverting the internal order of the nation and destroying its political, economic, and social system.”

Olivera Castillo was sentenced to 18 years in prison, parts of which he spent in State Security Department confinement at Villa Marista, the Guantánamo provincial prison, the Guantánamo provincial hospital, and a prison infirmary in western Matanzas province. Freed last December 6, he was among a half-dozen imprisoned journalists released on medical parole in 2004. After his release, the 43-year-old editor discussed with CPJ his early career in the state media, his professional evolution, his imprisonment, and his plans for the future. Here are translated excerpts of his interview with CPJ’s Sauro González Rodríguez:

SG: Tell us about your work for the official media.

JOC: From 1983 to 1993, I worked at the Cuban Institute for Radio and Television as an editor. During the decade I worked at this state-owned entity, I spent two years in the national television news system where news programs, news reports are made. I had a close experience with all the censorship, the self-censorship, and all the news manipulation that takes place in the official media.

SG: Describe this climate of self-censorship.

JOC: Propaganda is very tightly controlled by a Central Committee agency called Revolutionary Orientation Department, where information and indoctrination policies are designed. All media are subordinated to the strategies devised by this agency. People fear crossing a line–they don’t know where it is or what the limits are–and that’ s where self-censorship comes in. They censor themselves for fear of retaliation.

SG: When and why did you decide to join the independent press?

JOC: One thing that had a profound effect were the events during perestroika and glasnost in the Soviet Union. That opened my eyes, made me ask myself some questions and search for answers. I began maturing as time went by, and then I was faced with how to break the barrier of fear, of terror, which is something natural in Cuba, part of our culture.

SG: Can you describe for us how independent journalism is done in Cuba? SG: Can you describe for us how independent journalism is done in Cuba?

JOC: We face shortages of materials, a lack of information sources. Everything conspires against you; everything is so adverse, particularly the way to send your reports abroad. There’s no computer network cheap enough for us to send our reports; phone communications are terrible.

Nevertheless, we have been able to articulate a nationwide movement of independent journalists. We even published a magazine that was shut down with our imprisonment, De Cuba magazine, which was developed by the journalists association Sociedad de Periodistas Manuel Márquez Sterling. The persecution, harassment, economic adversities, lack of proper technology–a number of factors conspired against our doing a quality job.

SG: Would you describe your arrest?

JOC: I was at my wife’s aunt’s house napping when plainclothes agents showed up with a search warrant. My wife woke me up, a bit scared, and they all came in and carried out an exhaustive search. They took many pictures of everything they confiscated, which wasn’t much: two old, worn-out typewriters, and many news stories; books on politics, economics, even world literature; and a small 8mm camcorder. When we went downstairs to go to my house, the street was blocked. There were several police cars and motorbikes; it was a huge police operation. People were terrified, and many were watching from their balconies.

The search at my house was very similar. While they were searching, one of them turned on a radio and tuned in the “Mesa Redonda” talk show–which was talking about us, about the crackdown taking place at the same time at many homes in Cuba, and they were using epithets to denigrate and slander us. Around 10, 10:30 p.m., I arrived in Villa Marista, where they carried out a thorough body search and gave me prisoner’s clothes.

SG: Were you expecting the arrest?

JOC: I wasn’t expecting it, honestly. I thought it would be what had happened many times before. When the political police didn’t want me to cover an event, they would simply knock on my door and tell me I couldn’t leave. I thought it was routine harassment. I never thought it would be the beginning of a terrible period in the history of Cuba JOC: I wasn’t expecting it, honestly. I thought it would be what had happened many times before. When the political police didn’t want me to cover an event, they would simply knock on my door and tell me I couldn’t leave. I thought it was routine harassment. I never thought it would be the beginning of a terrible period in the history of Cuba

.

SG: Tell us about your experiences in prison.

JOC: To feel that you’re imprisoned, are surrounded by walls and bars everywhere, without reason, it’s a double shock that you suffer. I spent 36 days in a cell with common criminals in Villa Marista. The four of us could not stand at the same time, that’s how small the cell was. There was no ventilation and we had a fluorescent lamp on 24 hours a day. The bathroom was a hole; the smell was unbearable.

Then the trial came. The trial was a sham, a grotesque sham. I only saw my lawyer 10 to 15 minutes before my court hearing was to start. I felt I had been convicted in advance. Thank God I had the strength of character and could face such a difficult situation. I did not keep silent. I defended myself against all the allegations prosecutors made, full of visceral hatred –I can’t forget that. I refuted all of them.

Then there was the distance. I was sent over 900 kilometers (560 miles) from my place of residence, which was an additional punishment for my wife and my children. I was first at the Combinado Provincial de Guantánamo, and we were placed with common prisoners for 17 days. Then we were placed in solitary confinement. We had an hour a day to get some sun. I began having pain in my bones, due to the cell’s humidity and the lack of sunlight. I was sick all of one year. The food arrived rotten sometimes, and the water was muddy and brown. I contracted parasites twice. I would tell the doctor: “Look, the food is poorly prepared and sometimes rotten. The water is contaminated; we should not drink it.” And she would say: “That’s not my problem. My problem is if you get sick.” Then there was the distance. I was sent over 900 kilometers (560 miles) from my place of residence, which was an additional punishment for my wife and my children. I was first at the Combinado Provincial de Guantánamo, and we were placed with common prisoners for 17 days. Then we were placed in solitary confinement. We had an hour a day to get some sun. I began having pain in my bones, due to the cell’s humidity and the lack of sunlight. I was sick all of one year. The food arrived rotten sometimes, and the water was muddy and brown. I contracted parasites twice. I would tell the doctor: “Look, the food is poorly prepared and sometimes rotten. The water is contaminated; we should not drink it.” And she would say: “That’s not my problem. My problem is if you get sick.”

And there were lots of insects: mosquitoes, scorpions, flies, ants, lizards. It was a terrible situation. All amid the indifference, the indolence by the medical services and the prison officers. I was later placed in a cell with common prisoners–pedophiles and murderers. Something terribly harsh and brutal goes on in Cuban prisons.

Hunger, alienation, the guards’ willingness to beat up prisoners who in many cases do not deserve it–the prisoners become so alienated that they turn to self-mutilation. I saw two people make a hot paste by melting plastic shopping bags and then put their hands inside this substance. They lost their hands, which were amputated, and were released on medical parole. Other people stab themselves; swallow wires, small spoons; take fluids that are harmful to their digestive system. To sum it up, it’s a world of horror.

After being jailed for a year, I was transferred to the Guantánamo Provincial Hospital. This happened a year after I had been requesting adequate medical attention. During the time I spent at the hospital, conditions improved. I would receive the hospital’s food, and there was a snack. I was like any other patient, except that I remained jailed at a ward for prisoners, living with common prisoners, which was not easy. But at least there was more ventilation.

SG: How was your relationship with other prisoners?

JOC: You have to apply a lot of psychology. You may get stabbed, because they traffic in pills and prisoners get high, particularly in Guantánamo. There’s also trafficking in knives. They make them at the prison and sell them for cigarettes. Fights also break out and you may be wounded; that’s very common. It’s a very difficult coexistence. I didn’t have any problems with common prisoners, but it’s a potential problem, particularly for political prisoners and prisoners of conscience in Cuba.

SG: What medical problems did you suffer?

JOC: I suffer from a colon disorder, and I need to avoid stress. The pain in my lower abdomen is terrible, and I may have bouts of diarrhea. All of this upsets my nerves, and it becomes a vicious cycle because then I have another crisis. I also suffered from high blood pressure, apparently because of stress and the harsh conditions. Like I said, I barely caught any sunlight during all the time I was jailed. When I was at the hospital, I would ask my guards, “Please, handcuff me and take me outdoors.” But they would reply, “No, no, because of security concerns.” So I would talk to the doctor and I would tell the guards they should give me at least an hour outdoors, and sometimes the guards would give me an hour, or half an hour, or nothing.

SG: Were you aware of the international protests over the imprisonments?

JOC: You don’t know how important it is for a political prisoner, for a prisoner of conscience to feel and see through your family and through phone calls what people were doing. We were desperate. I would ask my relatives what CPJ was doing, what Reporters without Borders was doing, what the Inter American Press Association was doing, what Amnesty International was doing, what many other people, including politicians and people of good will were doing. That was very important from a spiritual point of view, to strengthen ourselves in those conditions and endure them. And this should not let up; it’s crucial for those journalists who are still in jail in conditions similar to those I have described. Their minds may be affected and so their bodies may be.

SG: How did your family cope during your imprisonment?

JOC: If you suffer in jail, your family suffers much more. Here, I have only my wife and my two children. My wife had to solve every problem and take care of the family–and she never stopped caring about me and denouncing all the injustices against me. Because of the distance to the prison, sometimes my family struggled to buy the transportation fare. They also struggled to provide for themselves, and bring things to me despite such a long trip. But my family stuck together.

SG: What is your view on the government crackdown and everything that has happened since?

JOC: I don’t think the crackdown was very successful. The international reaction has been very strong, massive, and sustained. I think the government underestimated that, and it has caused the government to lose a very large amount of prestige. The independent press has moved forward, and so have the trade unions, political parties, and human rights activists. So, I believe that in political terms the government hasn’t won anything. However, the language of confrontation persists and this is very dangerous. We can’t rule out that the government won’t take drastic measures, although smaller in scale. They could imprison three, four persons every few months, and it wouldn’t draw international attention. JOC: I don’t think the crackdown was very successful. The international reaction has been very strong, massive, and sustained. I think the government underestimated that, and it has caused the government to lose a very large amount of prestige. The independent press has moved forward, and so have the trade unions, political parties, and human rights activists. So, I believe that in political terms the government hasn’t won anything. However, the language of confrontation persists and this is very dangerous. We can’t rule out that the government won’t take drastic measures, although smaller in scale. They could imprison three, four persons every few months, and it wouldn’t draw international attention.

SG: Do you feel inhibited from working as a journalist again?

JOC: I have a refugee visa and I’m not a healthy person. I’m thinking about my family. I have been 12 years, including those two in prison, trying to create a space and I think we have been successful in establishing an independent press, a cornerstone of a future democracy. It’s been 12 years I have invested in this, and now I have to think about my family, my children.

SG: What are your plans for the future?

JOC: I think one day I’ll be able to leave Cuba. I don’t know how I’m going to do in the United States; I don’t know whether I will settle there permanently. I would like to keep writing, working as a television editor, but I know it won’t be easy. First I want to protect my family, my children, and above all, I want to cope better with my illness. One thing I do know for sure: I’ll never renounce my principles. I will always support a plural, inclusive society wherever I am. Nobody should be discriminated against because of his or her ideology. And all ideological lines should have their own media, their own way of expressing ideas and sharing them with other people. I will always defend these ideas. I took them up one day, haven’t renounced them and never will–let alone now.

|