Violence grips this booming border city two years after leaders of the powerful Tijuana drug cartel were arrested or killed, leaving rival gangs to shoot it out in these bustling streets in a battle over lucrative drug smuggling routes.

By Joel Simon and Carlos Lauria

TIJUANA, Mexico

Violence grips this booming border city two years after leaders of the powerful Tijuana drug cartel were arrested or killed, leaving rival gangs to shoot it out in these bustling streets in a battle over lucrative drug smuggling routes. Editor Francisco Ortiz Franco, gunned down in broad daylight in a quiet neighborhood near downtown Tijuana on June 22, is believed to be a victim of this bloody turf war.

Ortiz Franco was killed in a well-orchestrated assassination just two blocks from state police headquarters. An editor and reporter at the muckraking weekly Zeta, Ortiz Franco was a quiet, unassuming, and meticulous journalist who had only recently begun to write about the drug trade. Federal prosecutors, while not discounting other possibilities, have publicly linked the murder to the Tijuana drug cartel, which is controlled by the Arellano Félix family. Investigators believe that Ortiz Franco was killed because of his work as a journalist and are considering stories he wrote about the Arellano Félix cartel as the probable motive.

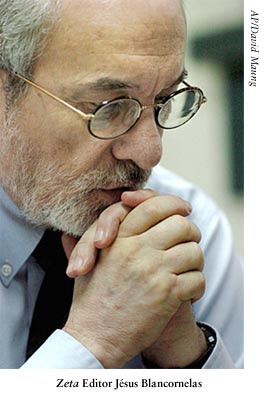

“The fact that federal prosecutors have taken over the case is a very important step forward,” says Jesús Blancornelas, the editor of Zeta. “There is political will at the highest level of the Mexican government to solve this crime. Now that the investigators have identified the suspects, they need to prosecute the killers and bring them to justice.”

On the morning of June 22, Ortiz Franco, known to his friends as Pancho, was returning from a doctor’s appointment in a largely residential block close to downtown. He had taken the week off from Zeta, where he was the tabloid’s co-editor, to be treated for facial paralysis that may have been induced by stress. On the orders of his doctor, he was taking it easy at home, leaving only to travel back and forth to the clinic. He gave the bodyguard who usually accompanied him the week off.

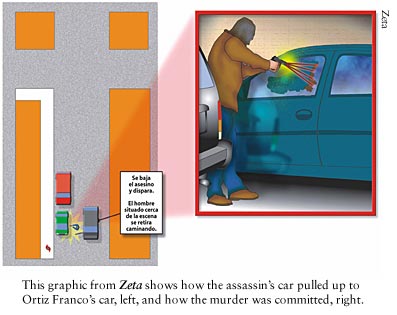

Ortiz Franco’s two young children had come with him to the clinic that morning, and they walked back to their car, a blue Mazda Comfort parked at the end of the block. He buckled 11-year-old Héctor Daniel and 9-year-old Andrea into the backseat, walked around the car, and got in. Before he could start the engine, a black Jeep Grand Cherokee pulled alongside, and a man wearing a black wool ski mask jumped out. The gunman fired four times from a .380-caliber handgun through the driver’s side window, hitting Ortiz Franco in the chest, head, and neck and killing him instantly, according to the editor’s widow, who has reviewed the case file. The killer climbed back into the Jeep Cherokee and sped away. The murder took mere seconds.

Ortiz Franco’s children scrambled out of the car and took refuge in the home of a neighbor. They later told their mother that the handgun made only a small popping sound that would not have attracted much attention. Police suspect that a silencer was used.

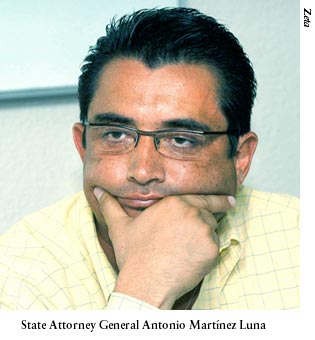

Five minutes after the murder, Blancornelas received an urgent phone call from State Attorney General Antonio Martínez Luna telling him that a Zeta staffer had been shot. Blancornelas quickly went through the office to account for his employees–forgetting in the panic that Ortiz Franco was out sick.

Five minutes after the murder, Blancornelas received an urgent phone call from State Attorney General Antonio Martínez Luna telling him that a Zeta staffer had been shot. Blancornelas quickly went through the office to account for his employees–forgetting in the panic that Ortiz Franco was out sick.

Blancornelas dispatched a photographer, his son Ramón Blanco, and a reporter, Lauro Ortiz Aguilera, the half-brother of Ortiz Franco, to cover the shooting. Arriving about 10 minutes after the attack, they found the crime scene cordoned off by yellow tape and a municipal police team conducting a forensic analysis. When they saw the Mazda, they realized to their horror that Ortiz Franco was the victim.

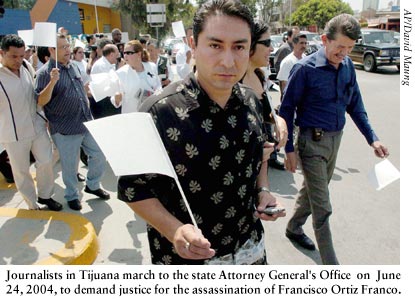

Later that day, Mexican President Vicente Fox telephoned Blancornelas to promise federal support for the investigation, which was then being carried out by the state police under Martínez Luna. Journalists in Tijuana and throughout Baja California organized marches demanding justice. The week after the murder, Zeta published an investigative article naming several possible suspects, including gunmen linked to the powerful Arellano Félix drug cartel.

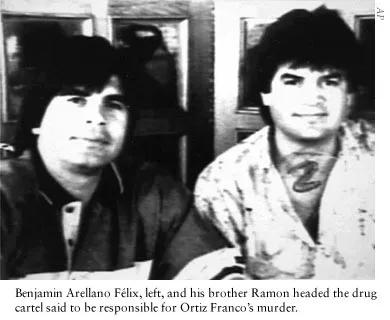

The Arellano Félix brothers, who run the cartel, were set up in the drug business by their cousin, Miguel Angel Félix Gallardo, who ran his drug empire out of Culiacán in Sinaloa state until he was jailed in 1989 for the murder of DEA agent Enrique Camarena. Félix Gallardo built his empire by smuggling locally produced marijuana and heroin across the border to the United States, but the Arellano Félix brothers took the business in a different direction.

Using their control over the lucrative Tijuana-San Diego border crossing as leverage, the Arellano Félix brothers made a strategic alliance with Colombian traffickers to move cocaine into the United States. They used the enormous profits to buy off state and municipal police and relied on brutal but selective violence against their rivals– particularly the new leadership of the Sinaloa cartel that emerged after Félix Gallardo was jailed.

Many of the Arellano Félix cartel’s most ruthless gunmen were recruited from violent street gangs in San Diego’s Barrio Logan. The leader of the Barrio Logan assassins was a veteran gangster named David Barron Corona, who earned the Arellano Félix family’s loyalty by saving two of the brothers from an ambush. In November 1997, Blancornelas published an article identifying Barron Corona as one of the top cartel enforcers.

Just weeks later, on November 27, Barron Corona and a team of assassins ambushed Blancornelas while he was on his way to work. Blancornelas’s bodyguard, Luis Valero, was killed in the attack, and Blancornelas was gravely wounded. The assassination attempt failed only because Barron Corona was killed by one of his own gunmen when a bullet ricocheted and struck him in the eye.

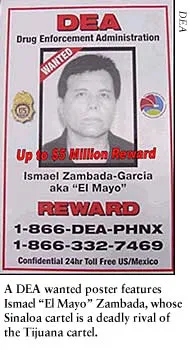

The attack on Blancornelas received intensive coverage in the Mexican and international media. Spurred by the popular outrage, the Mexican government launched a counteroffensive against the cartel, rounding up many top lieutenants, including the cartel’s financial mastermind, Jesús “Don Chuy” Labra Avilés. In March 2002, Mexican authorities arrested cartel leader Benjamín Arellano Félix. A month earlier, his brother Ramón, the cartel’s chief enforcer, was killed in Mazatlán in what was widely reported as a trap set by the Sinaloa cartel, led by Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada.

“The Arellano Félix organization has been damaged by recent killings and arrests,” says Special Agent John Fernandes, who heads the DEA’s San Diego office. “This has created an opportunity for other groups to gain territory.” Specifically, they opened the door for Zambada and the rival Sinaloa cartel to move into the border city, several sources say.

Journalists in Tijuana report a surge in violence, attributing it in part to the move by the Sinaloa cartel to infiltrate the city. State Attorney General Martínez Luna disputes this claim but acknowledges that there have been a number of “spectacular crimes” that have drawn public attention. Shootouts and executions have become commonplace in downtown Tijuana this year, but few were as brazen as the murder of former Assistant State Attorney General Rogelio Delgado Neri, who was gunned down while having a drink at Ruben’s Hood bar in January.

The battle also involves political control, including influence over the state and municipal police, according to Tijuana human rights activist Víctor Clark. “Zambada has a presence here through his relationships with police, businesspeople, and politicians,” Clark says. “The Sinaloa cartel has begun to buy the loyalty of former Arellano associates, and they are providing information to Zambada.”

While weakened, the Arellano Félix cartel continues to spread around millions of its own in bribes to municipal, state, and federal police, FBI Supervisory Special Agent John J. Blake says.

The corruption that pervades Tijuana’s public agencies has had a profound impact on the press. Many of the sources journalists use in Tijuana, from police to government officials, have links to the cartels and a vested interest in passing along to the media damaging information about rival organizations. Though cognizant of the overall risks, journalists are typically unaware of the specific relationships. Inevitably, members of the media fall into two camps: the few who follow up on these leads and thus put themselves in danger, and the many who simply shy away from sensitive news.

Ortiz Franco seldom wrote about drug trafficking during his long tenure at Zeta, but he began to develop new sources in the months before he was killed. In April, he interrupted a vacation in Las Vegas to meet with a source in Mexico City, according to Blancornelas. After that meeting, Ortiz Franco wrote a story alleging that an Arellano Félix lieutenant named Arturo Villarreal Albarrán (“El Nalgón”) had led the January 21, 2004, hit on former prosecutor Delgado Neri. Ortiz Franco was so nervous about the story he asked that it run in Zeta under Blancornelas’s byline. Blancornelas agreed, using his colleague’s reporting to rewrite the story in his own style. Villarreal could not be located for comment.

Blancornelas said the source for that story was a lawyer in Delgado Neri’s law office named David Valle. Analysts and legal sources say there is wide, if unproven, speculation that the Arellano Félix cartel killed Delgado Neri because he had made a deal with rival traffickers.

Martínez Luna disputes that notion, saying that Delgado Neri left the state prosecutor’s office because of “operational” issues, and that he was killed for refusing to help a group of drug traffickers.

Blancornelas accuses Valle of giving Ortiz Franco’s name to the traffickers who killed him. He points out that the Delgado Neri story was published under Blancornelas’ byline and that only Valle, as the main source in the story, could have known that Ortiz Franco had done the reporting. Valle has gone into hiding along with a second lawyer from Delgado Neri’s office and could not be reached for comment.

A few weeks after the Delgado Neri story, Ortiz Franco published a second story on drug trafficking, this one under his own byline. On May 4, FBI Special Agent Blake held a press conference in San Diego and made public photographs from dozens of fake police credentials used by Arellano Félix cartel members. Blake noted during the press conference that the men in the photographs had worn the same jacket and tie, suggesting that the photos were mass-produced. In his May 14 story, Ortiz Franco drove home this point, noting that “according to Zeta‘s sources, the participation of someone from the state Attorney General’s Office was necessary” to prepare the credentials.

Ortiz Franco’s story didn’t break much news, but by publishing the photographs prominently in a Tijuana newspaper he deeply angered the traffickers. As one source notes about the men in the photos, “These guys lived double lives. Now, all of a sudden, their kids know daddy is not really a policeman.”

Murder is a state crime in Mexico, and the initial investigation into the Ortiz Franco killing was headed by the state Attorney General’s Office under the direction of Martínez Luna.

This made Blancornelas deeply nervous. The state police in Baja California have a long history of corruption and ties to the Arellano Félix cartel. In one notorious incident from March 1994, state police protecting one of the Arellano brothers shot it out with federal police in Tijuana and then helped the drug trafficker escape.

To many Tijuana reporters who spoke with the Committee to Protect Journalists, the fact that Ortiz Franco was murdered just two blocks from state police headquarters suggests police complicity or indifference. For Blancornelas, that sense was compounded by the failure of state police to arrive at the crime scene until about 30 minutes after the murder, according to the account of Ramón Blanco, the Zeta photographer. Blancornelas was also disconcerted by the call from Martínez Luna minutes after the murder informing him that “someone from Zeta” had been killed. How, Blancornelas wonders, did Martínez Luna know this if his officers had not even arrived at the crime scene?

Martínez Luna told CPJ that he learned that a Zeta reporter had been shot from Tijuana’s emergency call center, which got the first call. It was not clear how the caller knew.

He said he believes that his agents were at the scene less than 10 minutes after the murder but “would have to check the file.” Martínez Luna pointed out that state police are detectives who investigate crimes, not first responders. He said his office pursued the investigation vigorously and was in frequent contact with Blancornelas.

Three hours after the crime, police recovered the getaway Jeep Cherokee after it was abandoned, apparently because the assassins switched to another vehicle. But there was little additional progress until August, when federal authorities took over the investigation. At an August 18 press conference in Tijuana, federal prosecutor José Luis Vasconcelos said they were taking over the case because several men under arrest for separate crimes had identified the killers and linked the murder to the Arellano Félix cartel. The connection to drug trafficking, a federal offense in Mexico, opened the door for federal investigators to take over.

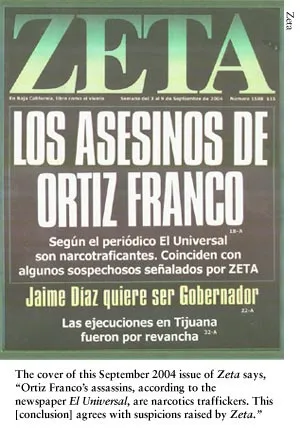

On September 2, the Mexico City daily El Universal published a story identifying members of the Arellano Félix cartel, including “El Nalgón,” as suspects in the Ortiz Franco murder. The story, which was attributed to an unidentified source in the federal Attorney General’s Office, also reported that “former state police agents, who are the principal operators of the Tijuana cartel in the city of Mexicali … are among the six suspected of carrying out the crime, and two of them are suspected of being the physical authors of the crime.”

On September 2, the Mexico City daily El Universal published a story identifying members of the Arellano Félix cartel, including “El Nalgón,” as suspects in the Ortiz Franco murder. The story, which was attributed to an unidentified source in the federal Attorney General’s Office, also reported that “former state police agents, who are the principal operators of the Tijuana cartel in the city of Mexicali … are among the six suspected of carrying out the crime, and two of them are suspected of being the physical authors of the crime.”

In an interview with CPJ in Tijuana, Martín Levario Reyes, the special federal prosecutor in charge of the investigation, confirmed that gunmen from the Arellano Félix cartel were the leading suspects, and that Ortiz Franco was likely killed in reprisal for his reporting. But Levario Reyes cautioned that the investigation was ongoing, and the Attorney General’s Office did not yet have enough evidence to request arrest warrants. Undercover agents from the AFI, the Mexican equivalent of the FBI, are conducting the investigation. CPJ sought additional records of the case in a September 29 letter to Vasconcelos, but the Attorney General’s Office denied the request, citing a Mexican law that prohibits releasing such information to anyone other than immediate family.

For Blancornelas, federal authorities’ willingness to discuss the case with CPJ was a positive sign. But the acknowledgement by Levario Reyes that federal authorities are not ready to issue arrest warrants troubles him and the Zeta staff, who are acutely aware that getting warrants for powerful drug traffickers requires great determination and political will.

Until then, the brazen murder of Ortiz Franco continues to cast a pall over the Tijuana press corps. The persistent violence against journalists, as well as the overwhelming impunity for those who commit such crimes, means that the drug traffickers are free to intimidate the press–and thus censor the news. On June 7, drug traffickers left a car loaded with marijuana in the parking lot of the Tijuana daily Frontera and then called a local television station to report that the newspaper was involved in drug trafficking. The station reported that the drug-laden car was a plant, but the traffickers’ message was clear: You accuse us of drug trafficking, but we can just as easily accuse you.

Until then, the brazen murder of Ortiz Franco continues to cast a pall over the Tijuana press corps. The persistent violence against journalists, as well as the overwhelming impunity for those who commit such crimes, means that the drug traffickers are free to intimidate the press–and thus censor the news. On June 7, drug traffickers left a car loaded with marijuana in the parking lot of the Tijuana daily Frontera and then called a local television station to report that the newspaper was involved in drug trafficking. The station reported that the drug-laden car was a plant, but the traffickers’ message was clear: You accuse us of drug trafficking, but we can just as easily accuse you.

Reporters at Zeta, including Blancornelas, project calm and determination, but the Ortiz Franco murder was a devastating blow. The names of its slain staffers–including editor Héctor Félix Miranda and security guard Luis Valero–remain on the newspaper’s masthead marked by black crosses, an eerie reminder of the cost the paper has paid. Meanwhile, Blancornelas is a virtual prisoner, moving only between home and office accompanied by 20 heavily armed bodyguards provided by the Mexican army.

“I feel remorse for having created Zeta,” says Blancornelas, four months after Ortiz Franco’s murder. “After losing three colleagues, I believe the price has been too high. I would have liked to retire a long time ago … [but] I cannot allow drug traffickers to think that they were able to crush Zeta‘s spirit, and our readers to believe that we are afraid.”

Joel Simon is the Deputy Director of CPJ. Carlos Lauría is CPJ’s Americas program coordinator.