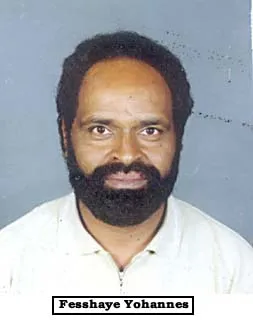

Fesshaye “Joshua” Yohannes is being held in a secret location in Eritrea.

Click here to add your name to a petition to free Joshua.

|

Fesshaye (who is also known as Joshua) is a popular writer, reporter, playwright, and founding editor of the Eritrean weekly newspaper Setit. The 47-year-old was imprisoned without charges in September 2001, along with the majority of Eritrea’s independent press corps, during President Isaias Afewerki’s widespread crackdown on political dissent. According to CPJ research, at least 18 journalists, including Fesshaye, are in prison in Eritrea today. Prior to the crackdown Setit and other private media had provided a forum for debate on the president’s increasingly autocratic rule. An open letter published in Setit on September 9, 2001, told the government that, “People can tolerate hunger and other problems for a long time, but they can’t tolerate the absence of good administration and justice.” Nine days later, with world attention distracted by the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, authorities in this tiny nation on the Horn of Africa moved swiftly to silence critics, and the government suspended all of Eritrea’s independent and privately owned newspapers for allegedly threatening state security and “jeopardizing national unity.” With the press out of business, the government canceled general elections. As a teenager, Fesshaye fought for Eritrea’s independence from Ethiopia. His military experience gave him connections to many of those in power today in Eritrea, and in 1994, he used those connections to help establish the beginnings of the country’s first independent media. Fesshaye’s paper, Setit, became the largest-circulation newspaper in the country, covering social problems including poverty, prostitution, and Eritrea’s lack of facilities to care for handicapped war veterans. But criticism from the independent press increasingly angered the government. In May 2001, knowing that Eritrea’s free press was far from secure, Fesshaye asked CPJ to help him create a journalists’ union to improve press freedom conditions. After the independent press was banned last September, Fesshaye’s initial instinct was to go into hiding. But, refusing to abandon his colleagues, he eventually surrendered to authorities. |

| Read War and Words, a report by Yves Sorokobi on the perils of practicing journalism in the Horn of Africa (from Dangerous Assignments, Fall 2002.) |

Languishing in prison since the fall of 2001, prominent Eritrean journalist Fesshaye Yohannes staged a hunger strike on March 31 with nine other colleagues in hopes of spurring their release. Instead, government officials transferred the journalists to an undisclosed location–and no one has heard from them since.

Languishing in prison since the fall of 2001, prominent Eritrean journalist Fesshaye Yohannes staged a hunger strike on March 31 with nine other colleagues in hopes of spurring their release. Instead, government officials transferred the journalists to an undisclosed location–and no one has heard from them since.