Although Uzbekistan’s president, Islam Karimov, has told the United States that he supports press freedom, old, repressive habits die hard.

Samarkhand, Uzbekistan –Here in Samarkhand, a city 170 miles (270 kilometers) southeast of Uzbekistan’s capital, Tashkent, a group of local reporters have left their jobs with mainstream Uzbek media outlets to free-lance for Internews, a U.S.-based organization that trains the journalists to produce television news programs that are syndicated to stations across Uzbekistan and Central Asia. Their reports address vital issues and ask tough questions–Mike Wallace would be proud.

There’s just one problem: The best of their work is never broadcast. Why? Because local news directors are too squeamish to put investigative journalism on the air. “Everyone is afraid of losing their jobs,” says one former editor.

To prove their point, the journalists show a video that contains a news report about a typhus outbreak in the eastern province of Jizak. The segment features interviews with people who contracted typhus after drinking contaminated water from public supplies, as well as confrontational encounters with medical authorities, who offer Soviet-style categorical denials. “There is no typhus in Jizak,” says one official. Even a doctor, confronted outside a hospital by an Internews reporter with a microphone, looks nervous and refuses to answer when asked if he’s seen recent typhus cases.

In the post-communist states of the former Soviet Union, independent reporting on public issues was supposed to be part of the transition to a democratic future. But this story on typhus–poignantly confirmed by victims, flatly denied by officials–will be seen by few, if any, residents of Uzbekistan. The Internews-trained journalists say that only one lone television station near Tashkent might dare to air the report. “Even though censorship has ended, station owners and editors still refuse to accept controversial material,” says reporter Gayane Oganova. And so, she says, more than a decade after the Soviet stranglehold on all media was loosened, “Nothing has changed.”

If you didn’t know better, Uzbekistan in the summer of 2002 feels an awful lot like being back in the U.S.S.R., the communist state that in 1991 collapsed into 15 independent countries, including Uzbekistan. Sure, there’s a slight thaw in the air, but old, repressive habits die hard. “Our officials are mostly from the communist era,” says a former city editor at the newspaper Samarkhand. “In an authoritarian system [like ours], it’s easier to rule people who are poor and uniformed.”

If you didn’t know better, Uzbekistan in the summer of 2002 feels an awful lot like being back in the U.S.S.R., the communist state that in 1991 collapsed into 15 independent countries, including Uzbekistan. Sure, there’s a slight thaw in the air, but old, repressive habits die hard. “Our officials are mostly from the communist era,” says a former city editor at the newspaper Samarkhand. “In an authoritarian system [like ours], it’s easier to rule people who are poor and uniformed.”

Interviews with a wide range of Uzbek journalists, human rights activists, and government officials suggest that Uzbek president Islam Karimov’s government remains intolerant of public criticism. The government monopolizes printing presses and newspaper distribution, finances the main newspapers, and has the power to grant or deny licenses to media outlets. Because Uzbek journalists remain vulnerable to intimidation from the police, security services, judges, prosecutors, government inspectors, and media regulators, a culture of Soviet-style self-censorship still pervades the local press.

Karimov is a product of the old communist system. He came to power in 1989, as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan at the height of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost, which encouraged openness as a way of reforming the Soviet system. Press freedom blossomed during the late 1980s and early 1990s. But after the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, Karimov became independent Uzbekistan’s first president. He methodically suppressed all public dissent, strengthening a system of prior censorship for media–a draconian step practiced in very few countries. In effect, he was reasserting Soviet-style control over the media.

Human rights groups have decried these policies, but recent events may make it easy for him to maintain such controls because, suddenly, Uzbekistan has new value on the international stage. Enter the United States. While Central Asia was not a strategic priority for the United States throughout the 1990s, in the immediate aftermath of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the United States was desperate for Central Asian allies in its war against the Taliban and al-Qaeda forces in Afghanistan. So Washington negotiated a deal last fall with Karimov that gave the U.S. military full access to the Khanabad air base, a former Soviet military facility near Uzbekistan’s southern border with Afghanistan. In exchange, the United States nearly quadrupled its annual financial assistance to Uzbekistan, from US$55 million in 2001 to some US$193 million this year.

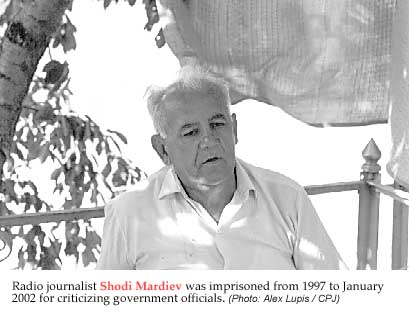

U.S. officials insist that the new bilateral relationship will have a positive impact on Uzbekistan’s harsh climate for freedom of expression and other human rights. The Karimov government has made some conciliatory gestures, especially in the wake of September 11, 2001. In January 2002, authorities amnestied several hundred political prisoners, including Shodi Mardiev, a 63-year-old reporter with the state-run radio station in Samarkhand who was wrongfully imprisoned in 1997 in reprisal for his critical stance toward government officials. Also in January and again in June, two separate groups of police and security officers were sentenced to prison for torturing and murdering detainees. And on March 5, a week before Karimov traveled to Washington to meet with President George W. Bush, the Justice Ministry finally agreed to register the country’s first independent human rights organization, a move authorities had resisted for years to ensure that activists remained vulnerable to legal harassment.

But severe government restraints on the media limited the impact of the registration. “It’s all well to be registered, but if you can’t [publish] your information in the media, then [you’re no] better off,” notes Marie Struthers, a researcher for Human Rights Watch.

In addition, Karimov and his senior government officials sternly and regularly lecture the local press about its “obligation” to follow political directives. In practice, the levels of fear and self-censorship are such that journalists rarely, if ever, question or debate major policy changes. And as Karimov’s press secretary Rustam Jumaev made clear in a roundtable meeting with editors in Tashkent last February, local media outlets were expected to inform the government in advance about all criticisms of state officials and policies that they plan to publish during the coming year. Moreover, Jumaev had called on editors to file monthly reports outlining their compliance with the plan.

Such statements and actions belie Karimov’s rhetorical insistence that the press is free in Uzbekistan. Last April, responding to criticism, he told Parliament, “Freedom of speech and the press is central to the given problems, and finds itself alongside these urgent tasks,” he said. “We want to build an open, legal democratic state, so we must do great work in this direction.”

But essentially what Karimov has done is privatize censorship by formally transferring responsibility from government employees to editors. And his parallel policies–aggressive media management coupled with public lip service to press freedom–were both reflected in the media reforms that followed.

On May 7, news broke that the State Press Committee had dismissed the director of its Agency for the Protection of State Secrets, Erkin Kamilov, a Karimov loyalist who had acted as the country’s chief media censor during the 1990s. A week later, government censors stopped reviewing newspapers prior to publication. During the next few weeks, local newspapers began publishing articles on previously taboo topics, such as unemployment, corruption in the education system, and past police abuses. Some interpreted the appearance of these articles as a sign that certain editors were willing to test the boundaries, while others suspected that the government had, in fact, ordered many to give the appearance of more critical reporting.

Although Kamilov’s dismissal and the abolition of prior censorship were certainly dramatic gestures of official support for press freedom, the government ensured that newspaper editors would be forced to pick up largely where the censors left off. At a meeting in Tashkent shortly after Kamilov was fired, State Press Committee head Rustam Shugalyamov warned the editors of Uzbekistan’s six official newspapers that authorities would now monitor newspaper content after publication. According to an editor who was present at the meeting, Shugalyamov said that the editors themselves would bear full responsibility for what they publish. The State Press Committee, the Soviet-era censorship office that continued working even after Uzbekistan gained independence “will now only monitor our articles after they are published,” says one newspaper editor.

Although the consequences of editorial error were not specified, the presidential administration was quick to set an example that was sure to encourage caution and self-censorship: On July 19, the editor-in-chief of the Tashkent-weekly Mohiyat, Abdukayum Yuldashev, was removed from his post. That day’s edition of the newspaper included an article about press freedom written by Karim Bakhriev, an independent journalist whose work has not appeared in print for years because the presidential administration had blacklisted him. According to one local journalist, “workers at the newspaper do not hide that they are under tremendous pressure from the presidential apparatus, and that every edition is read by the publisher,” who censors the paper.

Although the consequences of editorial error were not specified, the presidential administration was quick to set an example that was sure to encourage caution and self-censorship: On July 19, the editor-in-chief of the Tashkent-weekly Mohiyat, Abdukayum Yuldashev, was removed from his post. That day’s edition of the newspaper included an article about press freedom written by Karim Bakhriev, an independent journalist whose work has not appeared in print for years because the presidential administration had blacklisted him. According to one local journalist, “workers at the newspaper do not hide that they are under tremendous pressure from the presidential apparatus, and that every edition is read by the publisher,” who censors the paper.

Several journalists say that editors have responded by hiring former government censors to inspect articles prior to publication. When asked about this, Shugalyamov smilingly concedes that the State Press Committee has played a role in placing the censors with newspapers. “According to our law, employers are obliged to help salaried staff find new jobs in the event of termination,” he says.

Two months after the formal abolition of prior censorship, Karimov’s true media strategy began to emerge. On July 3, he decreed that the old State Press Committee should be replaced by a new state-run press agency with a mandate to monitor the media, according to local press reports. The Uzbek Press and Information Agency will have the power to suspend media licenses and official certificates of registration for “systematic” breaches of Uzbekistan’s restrictive media and information laws. It is also supposed to ensure that the government does not violate the rights of media outlets.

Local independent journalists remain skeptical of the agency’s willingness to defend them, however, considering that its new director, Rustam Shagulyamov, is a Karimov loyalist and former chairman of the State Press Committee. “He is a bad influence on the development of the Uzbek media because he belongs to a category of people who have a communist mentality,” says one press freedom advocate.

These journalists say that the end of censorship has actually made the Uzbek press more vulnerable to official pressure. “Editors had a different life with censors. They felt free to make a mistake and were not worried because censors would take out any sensitive material,” says one editor. “But now they are doing this job, and if some material is not consistent with the law, they can be sued.”

Bobomurod Abdullaev, a Tashkent-based correspondent for the London-based Institute for War & Peace Reporting (IWPR), says that he and his colleagues now expect “even more monitoring of their activities and many lawsuits.” As proof, Abdullaev points to an Interior Ministry document, dated April 6, instructing provincial anti-terrorist units to collect photographs and personal information of Uzbek journalists employed by the BBC and U.S. government-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), as well as opposition party activists.

The government also exerts pressure on local media outlets by tightly controlling media licenses. The broadcast licensing procedure is especially cumbersome and politicized. Numerous government agencies are represented on the Interagency Coordination Committee, which issues licenses for broadcast outlets. “What kind of radio and television coverage of these government agencies can there be if they are deciding [who gets a license]?” asks Khalida Anarbaeva, managing director of the Tashkent office of Internews.

Since Uzbekistan is the only former Soviet republic that regularly imprisons journalists in retaliation for their work, journalists also fear politically motivated criminal prosecution. According to research by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), three members of the media are currently imprisoned in Uzbekistan for their work. In March 1999, Muhammad Bekjanov and Iusuf Ruzimuradov were sentenced to 14 and 15 years in prison, respectively, for distributing the newspaper of the banned opposition party Erk. And in August 2001, Madzhid Abduraimov, of the national weekly Yangi Asr, was convicted of extortion and sentenced to 13 years in prison for his reporting on alleged corruption at a local grain production company and his coverage of other criminal activity. (CPJ is investigating several unconfirmed reports of other journalists in Uzbekistan who may be in jail for their work.)

This very real threat of imprisonment has forced other journalists into exile. Shukhrat Babadjanov, director of the independent TV station ALC in Urgench, had been fighting authorities for nearly two years after the politically motivated closure of his station. In August 2001, he fled the country, later telling CPJ that he feared authorities intended to silence him by putting him in prison on spurious forgery charges.

Many journalists in Uzbekistan argue that Karimov’s secretive and centralized rule makes it difficult to report accurately on the government. Karimov runs the country using what Uzbeks call telefonaya prava, or “law of the telephone,” a system in which bullying calls from the presidential administration substitute for the rule of law.

“Officials are afraid to be quoted because the whole system is built so that only the presidential administration is generating ideas,” says one Uzbek journalist. “It can take days to get an official reaction from officials because they must check with their ministry, who checks with the presidential administration.”

Galima Bukharbaeva, another IWPR correspondent in Tashkent, says that local journalists find it “impossible to get even basic government information from press officers,” making it difficult to write well-sourced articles.

In an effort to control the flow of information, Uzbek authorities also continue to obstruct foreign broadcasters such as the BBC and RFE/RL, which is broadcast from outside the country. A decade ago, RFE/RL signed a contract with Uzbek authorities to broadcast on medium-wave and FM frequencies within Uzbekistan. But local officials, evidently wary of allowing uncensored information on mainstream domestic airwaves, have so far declined to honor the deal.

Still, as the meeting with journalists in Samarkhand shows, there is no shortage of Uzbek journalists who are interested in doing aggressive, objective reporting. Because the mainstream press is so tightly controlled, however, most of these people either work as stringers for foreign news agencies or else produce articles and video packages that are passed, samizdat-style, around an underground community of like-minded intellectuals and activists. “We work on our own now,” says reporter Oganova. “And there’s no censorship at Internews, so we pass on our material to them.”

Many of these journalists, like the ones who produced the typhus report, prefer uncensored reporting for a tiny audience to censored work for a mass audience. Explaining why he left the mainstream press, one journalist tells how he once submitted a story about the price of eggs in Samarkhand to the national newspaper Hurriyet. The gist of the story was that the price of eggs, as everyone in Uzbekistan knows, always shoots up just before major holidays–something that isn’t supposed to happen in the rigidly controlled Uzbek economy.

The reporter wrote that merchants in Samarkhand usually raise the price of eggs from a few som (US$1 equals approximately 1,050 som) to 100 som before a holiday. But his editor changed 100 som to 40 som in the published version, apparently because he didn’t want to offend government officials in Samarkhand.

“I’m afraid to write any more articles like that,” the journalist says. “People will think I’m an idiot.”

The existence of this underground investigative press suggests that Uzbekistan could easily become a more open society if the media were simply allowed to hold its government accountable to the people and to the law.

Alex Lupis is CPJ program coordinator for Europe and Central Asia. Richard McGill Murphy is the former editorial director of CPJ.