In the current battle between the Venezuelan media and President Hugo Chávez Frías, journalists are being used as ammunition.

Caracas, Venezuela–Over coffee one morning in May at a café not far from Plaza Bolívar in downtown Caracas, a journalist from one of Venezuela’s private leading daily newspapers is describing the events surrounding the April coup and the disastrous implications they have for the nation’s media. She doesn’t mince her words. “The president is on one side and the media owners are on the other,” she says. “We journalists are in the middle, completely defenseless, exposed to attacks from both sides.”

What this beat reporter describes is becoming an increasingly common phenomenon in Venezuela. The result is that journalists–caught between Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez Frías’ inflammatory rhetoric and the active political role that media publishers and editors have taken–find themselves victims of attacks from the public.

In fact, says the journalist, “Whenever I go out on the streets, I immediately take my credentials off and hide them.”

Journalists from state-run media outlets also feel like victims. “It can bring risks for journalists to maintain balance, because you may be considered a traitor by both sides, who believe that the role of a journalist is to be a politician, that a media outlet is a revolver, and that journalists are bullets, ” says Ernesto Villegas, a journalist formerly with the daily El Universal and now with the state-run television station, Venezolana de Televisión (VTV).

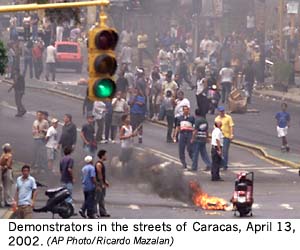

This past spring, Venezuelan journalists realized just how bad the situation had become. On the afternoon of April 11, following three days of protests by anti-government demonstrators, the Venezuelan government pre-empted broadcasts from the six local television stations (only one of which is state-run) for a message from President Chávez. During the address, private stations split the screen to continue covering the protests. Upset by this decision, Chávez ordered the stations closed and accused them of conspiring to overthrow his government.

This past spring, Venezuelan journalists realized just how bad the situation had become. On the afternoon of April 11, following three days of protests by anti-government demonstrators, the Venezuelan government pre-empted broadcasts from the six local television stations (only one of which is state-run) for a message from President Chávez. During the address, private stations split the screen to continue covering the protests. Upset by this decision, Chávez ordered the stations closed and accused them of conspiring to overthrow his government.

The following morning, Chávez was ousted and Pedro Carmona, president of Fedecámaras, the country’s most powerful business group, was appointed to head the new, military-backed cabinet. But news of Chávez’s ouster resulted in more protests, this time by his supporters, and within 48 hours, military officers loyal to Chávez had reinstated the president.

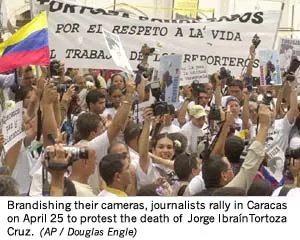

By April 14, violence had taken at least 50 lives, including that of Jorge Ibraín Tortoza Cruz, a veteran photographer who had worked for the Caracas daily 2001 for the last 11 years. Tortoza was shot and later died from his wounds. Another photographer, Jorge Recio, is paralyzed from the chest down. (It is unclear who shot the photographers or whether they were specifically targeted. Some photographers say that unidentified gunmen positioned on rooftops shot them, while others say that National Guard troops or the Caracas Metropolitan Police fired at them. But they all agree that they were targeted because they were trying to document the events. The National Assembly, Venezuela’s parliament, is currently debating a law that would establish a truth commission to investigate the events of April 11.)

In more than a dozen interviews with the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), journalists said they felt like cannon fodder in this struggle between Chávez and the media, who have become increasingly anti-Chávez. Some journalists charged that editors told them not to cover pro-Chávez events or rewrote copy to put the opposition in a better light. “If the journalist collects the facts, as they happened, and gives them to the newspaper, the information is then manipulated to make the situation seem different,” says the Caracas daily journalist, pausing to take a sip from her coffee. “And who is affected by this? The journalist, because it’s his or her byline.”

Most Caracas-based dailies, including the national circulation El Nacional and El Universal, did not publish on April 14, saying that they feared being attacked by Chávez supporters. (Both El Nacional and El Universal evacuated most of their personnel the previous day.) Private television stations featured little, if any, news coverage of the pro-Chávez demonstrations. The station managers deny that they chose to ignore the pro-Chávez demonstrations and say that they ordered their reporters not to cover the protests for safety reasons. “The reports coming into the station were about violence, death, and looting. We sacrificed our ratings, our credibility with viewers, our freedom of expression by deciding not to broadcast images of violence and looting,” said Alberto Federico Ravell, general director of the 24-hour news channel Globovisión, in a televised address in which he attempted to express his regret over the situation.

Many journalists, however, have pointed out that the stations covered violent events leading up to the coup and that the events could have been covered without exposing journalists to unnecessary risks.

Although much of the press supported Chávez in his sweeping rise to power in 1998, since being elected, his relationship with the media has been marked by confrontation. Chávez and his supporters accuse the Venezuelan press of distorting the facts and undercovering his administration’s achievements. During his radio and TV program, “Aló, Presidente,” Chávez has lambasted his critics among the media. In addition, Chávez has used the cadenas_his nationwide simultaneous radio and television broadcasts_to single out individuals for censure, often naming journalists and media owners.

Although much of the press supported Chávez in his sweeping rise to power in 1998, since being elected, his relationship with the media has been marked by confrontation. Chávez and his supporters accuse the Venezuelan press of distorting the facts and undercovering his administration’s achievements. During his radio and TV program, “Aló, Presidente,” Chávez has lambasted his critics among the media. In addition, Chávez has used the cadenas_his nationwide simultaneous radio and television broadcasts_to single out individuals for censure, often naming journalists and media owners.

Venezuelan human rights organizations say that although freedom of expression is present in Venezuela, full guarantees for the exercise of such freedom are lacking, as illustrated by several recent judicial rulings that have permitted prior censorship or have penalized criticism of public officials.

However, says Teodoro Petkoff, a former politician and an editor at the opposition daily TalCual, Chávez’s “discourse has so far not been matched by any repressive measure…. It is true that the president is aggressive, but we are very aggressive with him, too. The problem that Chávez has created,” adds Petkoff, “is that his discourse, in some popular sectors that support him, has generated aggressive attitudes against the media.”

Attacks against reporters, cameramen, and photographers are not a new phenomenon in Venezuela. During the last four decades, Venezuelan presidents often attempted to silence the media’s critical coverage. Their techniques ranged from violent threats and overt censorship to denials of preferential exchange rates for the import of newsprint. For instance, according to CPJ research, during 1992, at least five media outlets in Venezuela were raided, censored, prohibited from circulating, or had copies of their publications confiscated by government authorities. And during the last 10 years, CPJ has documented 18 attacks involving 34 journalists, most of which occurred in the first half of the 1990s, under the administrations of former presidents Carlos Andrés Pérez and Rafael Caldera.

But under Chávez, the sparring between the government and the media has escalated in this already divided nation. For instance, Chávez has coined the opposition, which includes the media, escuálidos (squalids), and the media have fired back at his supporters, calling them “chavista mobs” and “vandals.” Chávez’s aggressive discourse has reinforced hostility toward the media among government supporters–who have occasionally resorted to attacking news crews–and has fostered a climate of fear and self-censorship among journalists, who now avoid covering pro-Chávez events.

But under Chávez, the sparring between the government and the media has escalated in this already divided nation. For instance, Chávez has coined the opposition, which includes the media, escuálidos (squalids), and the media have fired back at his supporters, calling them “chavista mobs” and “vandals.” Chávez’s aggressive discourse has reinforced hostility toward the media among government supporters–who have occasionally resorted to attacking news crews–and has fostered a climate of fear and self-censorship among journalists, who now avoid covering pro-Chávez events.

The harassment has also touched international media outlets, such as CNN. For instance, some opposition supporters have expressed anger that CNN covered April’s pro-Chávez demonstrations and government press conferences.

Of course, the media’s foray into the political arena only worsens the risks that Venezuelan journalists face. Indeed, some high-profile journalists have become such ardent Chávez opponents that many Venezuelans say the media, in filling the void left by discredited political parties, has become the opposition.

The atmosphere inside state-run media mirrors the environment in private media. To be sure, most previous Venezuelan governments have used the official media to advance their own partisan interests. But, according to journalists who work for state-run media, the situation has worsened under President Chávez. These journalists say that Chávez has treated the state press–which includes the radio station Radio Nacional, VTV, and Venpres–as his own private media forum. And, according to one Radio Nacional journalist, “There is a witch-hunt inside the radio station: either you are a chavista or you are a squalid.”

The atmosphere inside state-run media mirrors the environment in private media. To be sure, most previous Venezuelan governments have used the official media to advance their own partisan interests. But, according to journalists who work for state-run media, the situation has worsened under President Chávez. These journalists say that Chávez has treated the state press–which includes the radio station Radio Nacional, VTV, and Venpres–as his own private media forum. And, according to one Radio Nacional journalist, “There is a witch-hunt inside the radio station: either you are a chavista or you are a squalid.”

“I’ve always argued that we have to cover both sides, but that’s not our communications policy,” says one journalist who works for the state press agency, Venpres. In other words, balanced reporting is hard to find.

The situation for journalists during businessman Carmona’s brief tenure during the coup attempt was not much better. Carmona-backed forces reportedly harassed journalists working for community media, which are noncommercial broadcasters serving local neighborhoods. Community media outlets in Caracas such as TV Catia, TV Caricuao, Radio Perola, and Radio Catia Libre said that police raided their offices and that some workers were detained. The majority of community media outlets are pro-Chávez.

Also under Carmona, the state television station, VTV, was taken off the air on the evening of April 11 after being occupied by military forces that joined the coup. It remained shuttered until April 13, when it was taken over by government supporters who brought it back on air.

Nobody can predict what the future holds for Venezuelan journalists, let alone for Venezuela itself. In fact, many Venezuelans worry that another military coup against Chávez may occur; according to recent news reports, both opposition supporters and Chávez’s followers are stockpiling weapons and ammunitions. Fearing that journalists will be primary targets if another coup happens, some newspapers are developing emergency plans to evacuate and track their journalists.

Nobody can predict what the future holds for Venezuelan journalists, let alone for Venezuela itself. In fact, many Venezuelans worry that another military coup against Chávez may occur; according to recent news reports, both opposition supporters and Chávez’s followers are stockpiling weapons and ammunitions. Fearing that journalists will be primary targets if another coup happens, some newspapers are developing emergency plans to evacuate and track their journalists.

In the past, whenever Chávez has ordered the attacks and harassment of journalists to stop, his followers have generally complied with his request. Although the president still occasionally denounces “communications media” in general, lately he has avoided singling out individual journalists. But continued press attacks this summer in which government supporters have beaten and verbally abused photographers and reporters suggest that the situation has gotten out of control.

And the victims in all this are the journalists, who are simply trying to do their jobs.

Sauro González Rodríguez is research associate for CPJ’s Americas program.