Burkina Faso’s ruling clan has endured two years of unrest sparked by the murder of a leading investigative journalist.

|

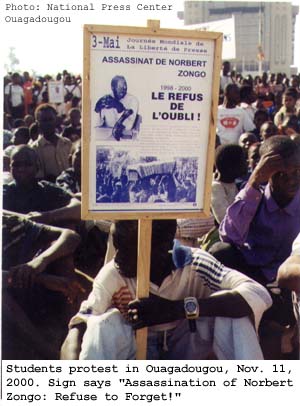

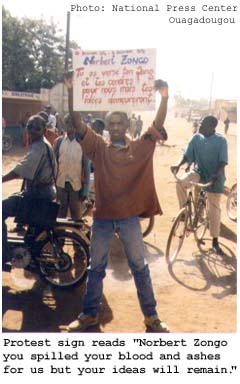

On December 13, 1998, Norbert Zongo and three friends were driving on a deserted road near Sapouy, some 50 miles outside the capital, Ouagadougou. Unknown individuals fired several automatic rifle bursts at the car, killing all four men. Then they torched the vehicle in an attempt to simulate a road accident. The chauffeur was suspected of stealing some 20 million CFA (US$27,000) from Compaoré. Autopsy reports suggest that Ouedraogo died after several days of savage torture. More than two years later, l’affaire Zongo still arouses passions. The case sparked a mass movement led by journalists and activists fed up with the Compaoré government’s alleged corruption and casual use of extreme violence to stifle dissent. After Zongo’s death, “people lost their fear, started a whole movement, and began to question authority, forcing the government to take small steps toward democracy,” said Jean Claude Meda, president of the Burkina Faso Journalists’ Association. In early 1999, President Compaoré promised that his government would not meddle in the work of an independent commission of inquiry set up to look into the Zongo affair. In May, the commission concluded that Zongo had been killed for investigating Ouedraogo’s murder. Warrant Officer Marcel Kafando and four other members of the feared Presidential Guard Regiment (RSP) were named as serious suspects in the murder. The commission also hinted that the officers might have acted on orders from Francois Compaoré. The government tried to short-circuit further investigations by promising financial compensation to the families of Zongo and the other victims. When this tactic failed, authorities resorted to classic stonewalling. A local judge who had charged François Compaoré with murder and “harboring a dead body” was removed from the case. And after three of the five RSP guardsmen were indicted on the same charges, the case was moved to a military tribunal, despite legal objections that as a civilian Francois Compaoré should be tried in a regular court. Over the next few months, Zongo demonstrations spread across the country, with everybody from high school students to market women’s associations joining in. And in early March of last year, the bureaucratic wall around the Zongo case began to crumble. On March 5, two dozen local judges issued a joint statement complaining about administrative and political pressure to maintain the status quo. During a Zongo rally on April 8, police beat several people unconscious and inflicted serious injuries on more than a dozen others. In response, a crowd of angry citizens ransacked the military court building in Koudougou, some 250 miles outside the capital, and burned it to the ground. At this point, the government abandoned covert manipulation in favor of open confrontation. On April 14, 2000, after the independent radio station Horizon FM aired a press release from Le Collectif calling for yet another Zongo rally, police stormed the station and shut it down. The state-run Supreme Council on Information (CSI) ordered the raid under Burkina Faso’s 1993 Information Code, which sanctions the immediate closure of media outlets charged with “endangering national security or distributing false news.” “The law is harsh, in accordance with the poor understanding local media have of what constitutes [public] information,” CSI official Bakery Hubert Pare told CPJ. “When a station incites public unrest, then it must suffer the consequences of its behavior.” A week after the closure of Horizon FM, unidentified individuals burgled the Ouagadougou Palace of Justice, making off with sensitive documents relating to the Zongo case. The thieves were never found. In early August, Kafando and two other RSP guardsmen went on trial for the murder of Ouedraogo. The trial brought more confusion than closure, however. Kafando and his colleagues claimed that Francois Compaoré and his wife had told them about the chauffeur’s alleged theft, but had not asked them to do anything about it. (The disappearance of the money was never proven.) The guardsmen also testified that Ouedraogo had been involved in a scheme to overthrow the government. In early January 2001, Kafando’s codefendant Edmond Koala was found dead in his prison cell “after a long disease,” according to a government press release. A few days later, the state prosecutor interrogated Francois Compaoré about the Zongo murder, and then let him go. The prosecutor’s office claims that Compaoré’s schedule for December 12-13, 1998 appears to be “in order.” In early February, Marcel Kafando was indicted for murder in the Zongo case. Kafando, already serving a 20-year sentence for Ouedraogo’s murder, is the first person to be formally accused of killing Norbert Zongo and his companions. The state prosecutor said that the indictment resulted from “contradictions noted in [Kafando’s] alibi for December 12 and 13 of 1998.” Doubtless hoping that the country was ready to move on, the government declared March 30 a national “Day of Forgiveness” [Read CPJ’s letter to the government]. But by all accounts, the people of Burkina Faso are not ready to forgive their brutal government. Human rights campaigners largely boycotted the March 30 observances. Norbert Zongo’s grieving relatives did not attend. |

|

Yves Sorkobi is Coordinator of the Africa Program for CPJ. |

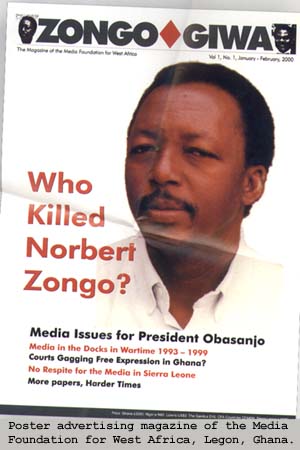

Zongo edited L’Indépendant, a muckraking Ouagadougou weekly. Before his death, the editor had been investigating allegations that François Compaoré, President Blaise Compaoré’s younger brother and chief advisor, took part in the January 1998 killing of his own chauffeur, David Ouedraogo.

Zongo edited L’Indépendant, a muckraking Ouagadougou weekly. Before his death, the editor had been investigating allegations that François Compaoré, President Blaise Compaoré’s younger brother and chief advisor, took part in the January 1998 killing of his own chauffeur, David Ouedraogo. In May and September 1999, members of the French press freedom advocacy group Reporters Sans Frontières were thrown out of Burkina Faso when they visited the country to investigate the Zongo affair. Three months later, in December, the Compaoré regime charged seven members of Le Collectif, a coalition of local independent journalists and human rights advocates, with “undermining state security” by organizing a demonstration of 70,000 people to call for closure in the Zongo affair. (The charges were later dropped.)

In May and September 1999, members of the French press freedom advocacy group Reporters Sans Frontières were thrown out of Burkina Faso when they visited the country to investigate the Zongo affair. Three months later, in December, the Compaoré regime charged seven members of Le Collectif, a coalition of local independent journalists and human rights advocates, with “undermining state security” by organizing a demonstration of 70,000 people to call for closure in the Zongo affair. (The charges were later dropped.) When asked whether he believed that Horizon FM had been silenced because it openly accused the presidential family of involvement in Zongo’s assassination, Pare took a deep breath. “Democracy is fine, but journalists have to know that the interests of the country come first,” he said. “Journalism is not about insulting state officials.” (Horizon FM reopened around May 29.)

When asked whether he believed that Horizon FM had been silenced because it openly accused the presidential family of involvement in Zongo’s assassination, Pare took a deep breath. “Democracy is fine, but journalists have to know that the interests of the country come first,” he said. “Journalism is not about insulting state officials.” (Horizon FM reopened around May 29.) The three guardsmen were found guilty of killing David Ouedraogo and sentenced to between 10 and 20 years in jail. The court also awarded the victim’s family 200 million francs (US$227,000) in damages. It would be another six months before authorities acknowledged any link between the death of Ouedraogo and the murder of Norbert Zongo and his friends. Meanwhile, authorities fanned popular discontent by cracking down on opposition rallies and issuing stern warnings to the media.

The three guardsmen were found guilty of killing David Ouedraogo and sentenced to between 10 and 20 years in jail. The court also awarded the victim’s family 200 million francs (US$227,000) in damages. It would be another six months before authorities acknowledged any link between the death of Ouedraogo and the murder of Norbert Zongo and his friends. Meanwhile, authorities fanned popular discontent by cracking down on opposition rallies and issuing stern warnings to the media.