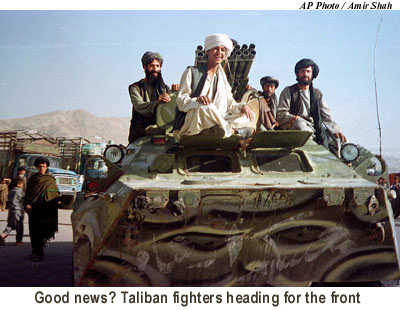

The Taliban are hardly press freedom champions. Even so, Afghan journalism is showing signs of life.

| “If a man fears death, he will accept fever,” says an old Afghan proverb. In a way, that’s how most Afghans felt when the Taliban militia swept to power three years ago. Compared with the brutal, corrupt warlords they replaced, the fervently religious Taliban seemed a breath of fresh air. | ||

| That’s also how Afghan journalists view the Taliban. The former religious students who control most of Afghanistan today are no great believers in press freedom, of course. But they have proved somewhat more tolerant of criticism than the warring factions that ruled Afghanistan until 1996.

Today, the Taliban Ministry of Information and Culture estimates that there are more than a dozen state-owned newspapers around the country. However, Kabul-based Because Afghanistan is largely an illiterate society, radio is the mass communication medium of choice. Bereft of music, Radio Kabul (now known as Radio Voice of Islamic Law) is heavily oriented towards religious topics. In the provinces, however, local media seem to enjoy greater independence, according to local journalists. In the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif, for example, a recent radio drama explored the racy topic of girls choosing their own husbands. While there is no explicit ban on independent journalism, state-owned publications and radio stations dominate the country’s media. This has been true in Afghanistan for at least a quarter of a century. Afghanistan’s last and only free press flourished during the so-called “decade of democracy” from 1963 to 1973 when it ground to an abrupt halt with the overthrow of King Zahir Shah. Later under President Muhammad Daud (1973-1978) and the Communist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (1978-1992) government control over the press tightened even further. Under the Communists, listening to Western radio broadcasts became a crime. The media became the means to spread ideological propaganda and Across the border in Pakistan, where anti-Soviet resistance groups were based, the story was no different. Through dozens of newspapers, magazines and leaflets, the resistance highlighted Soviet and communist regime atrocities in an effort to garner international support for their cause.

Recently, Afghan journalists held a conference in Peshawar to discuss ways to promote independent media in Afghanistan, including a national daily newspaper to be distributed inside the country. But they recognized the dangers of reporting in a country where press freedom has not entered the national vocabulary. Take Mirwais Jalil, a young BBC reporter who was brutally murdered in 1994. One of the mujahidin faction leaders ordered Jalil’s execution shortly after being interviewed by him on the outskirts of Kabul. Afghan journalists often cite the case to underline the dangers they face. For their part, the Taliban have not resorted to violence against journalists, unless you count last year’s Taliban assault on the Iranian consulate in Mazar-I-Sharif, where an Iranian reporter was killed along with nine Iranian diplomats. (The Taliban blamed the deaths on renegade forces.) Even so, local stringers for international news organizations tend to publish their work anonymously. “If I didn’t have to do it to make a living, I would never want to work as a journalist,” said the head of one Peshawar-based news agency. “Everyone is unhappy with you: the Taliban are unhappy, the opposition is unhappy …” That’s true for journalists all over the world, of course. But in Afghanistan, making a subject unhappy can be fatal, as it was for Mirwais Jalil. Masood Farivar grew up in Afghanistan and fought in the mujahidin resistance movement before attending Harvard College. He is now a reporter with Dow Jones Newswires. |

This is not to say that the Taliban are press freedom champions. A Peshawar-based Afghan woman journalist was reportedly jailed when she visited Afghanistan earlier this year, and two Pakistani reporters were detained on espionage charges after visiting opposition-held territories in northern Afghanistan. Several Peshawar-based Afghan journalists reported receiving threatening calls after writing critical articles about the Taliban. The latter deny threatening journalists, although Taliban officials say privately that they oppose “independent” newspapers because these could become propaganda vehicles for the opposition.

This is not to say that the Taliban are press freedom champions. A Peshawar-based Afghan woman journalist was reportedly jailed when she visited Afghanistan earlier this year, and two Pakistani reporters were detained on espionage charges after visiting opposition-held territories in northern Afghanistan. Several Peshawar-based Afghan journalists reported receiving threatening calls after writing critical articles about the Taliban. The latter deny threatening journalists, although Taliban officials say privately that they oppose “independent” newspapers because these could become propaganda vehicles for the opposition.