Dangerous Assignments

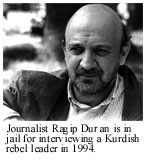

The imprisonment of Ragip Duran on June 16 marked another blow against press freedom in Turkey. But Duran, Istanbul correspondent for the French-language daily Liberation and several news agencies, did not go quietly. Neither his colleagues nor his conscience would permit it.

At a gathering of the Turkish Journalists’ Association (TJA) before he boarded the bus that would take him to Saray Prison, Duran was cheered by scores of supporters. “I will not be the first journalist who will be imprisoned because of my thoughts and articles,”he said. “I hope I will be the last.”

TJA chairman Nail Güreli epitomized the sense of siege among journalists, who he said are being imprisoned or silenced by powerful forces fearful of the truth. “Those who act in the spirit of press freedom are paying a price,” said Güreli. “Duran is one of those private soldiers who has struggled for his freedom and is being jailed.”

Duran was convicted in December 1994 of propagandizing on behalf of an outlawed organization under Article 7 of Turkey’s Anti-Terror Law. The charge stemmed from an interview with Abdullah Oclan, leader of the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), which has been fighting Turkish rule of the Kurds in eastern Anatolia since 1984. The interview appeared in the now-defunct daily Özgür Gündem, on April 12, 1994. Duran, who has also worked for the British Broadcasting Corporation and Agence France-Presse, was sentenced to seven and half months in prison; he appealed, but the Court of Cassation ratified the sentence on October 23, 1997. On February 16, 1998, a state prosecutor granted Duran a four-month postponement of his sentence, which expired on June 16.

Duran was convicted in December 1994 of propagandizing on behalf of an outlawed organization under Article 7 of Turkey’s Anti-Terror Law. The charge stemmed from an interview with Abdullah Oclan, leader of the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), which has been fighting Turkish rule of the Kurds in eastern Anatolia since 1984. The interview appeared in the now-defunct daily Özgür Gündem, on April 12, 1994. Duran, who has also worked for the British Broadcasting Corporation and Agence France-Presse, was sentenced to seven and half months in prison; he appealed, but the Court of Cassation ratified the sentence on October 23, 1997. On February 16, 1998, a state prosecutor granted Duran a four-month postponement of his sentence, which expired on June 16.

Friends, colleagues, and family escorted Duran to the bus, handing him flowers as he boarded. Colleagues and relatives accompanying him on the trip kept up the chant “Free press cannot be silenced” and sang Turkish liberation songs, while Duran’s cellular phone brought a stream of good wishes from around the world. Packed into cars, other supporters followed the bus on its two-hour trip from Istanbul to the northwestern town of Tekirdag, where the Social Democrat mayor treated the convoy to lunch.

In a poignant gesture, Ocak Isik Yurtçu, a former editor of Özgür Gündem who was released from Saray Prison last summer, gave his prayer beads to Duran. Yurtçu, a 1996 recipient of the Committee to Protect Journalists’ International Press Freedom Award, had been imprisoned since 1994 for violations of the Anti-Terror Law and Penal Code. He was freed in August 1997 under a partial amnesty for editors enacted just weeks after a CPJ delegation met with Prime Minister Mesut Yilmaz and other government officials to press for the release of imprisoned journalists and reform of laws criminalizing journalism.

The Yilmaz government’s promises to end the jailing of journalists are a year old, but changes in Turkey’s treatment of the press have not materialized in time to keep Ragip Duran out of prison. More than 100 people marched with Duran to the gate of Saray Prison, where he bid them farewell until 1999 and surrendered to the armed soldier at the gate. As the crowd looked on, the guard searched him and led him inside.

Nilay Karaelmas is a free-lance writer based in Turkey and a consultant to CPJ.