Iraqi Kurdish political leaders have cultivated an image of freedom and tolerance, but that increasingly clashes with reality. As the independent press has grown more assertive, attacks and arrests have increased.

| SULAYMANIA, Iraq A slender frame and quiet demeanor belie the fiery online presence of Nasseh Abdel Raheem Rashid, a 29-year-old biology student turned journalist. As a contributor to Kurdistanpost, a popular Kurdish-language news site that has incensed Iraqi Kurdish officials, Rashid has railed against the political order in Iraqi Kurdistan and the actions of unscrupulous political officials. In an article published last summer, he took aim at veteran Kurdish fighters, or peshmerga, who had once fought against Saddam Hussein, but who should now “be tried for looting the fortunes and properties of the people.” It was only a matter of time before Rashid’s biting criticism would bring him unwelcome attention. As he strolled through the central market of his hometown of Halabja in eastern Iraqi Kurdistan last October, four armed men wearing military uniforms forced him into a waiting Nissan pickup, bound his hands and legs, and covered his head with a sack. “I didn’t know where I was going. They drove around for a few hours and then went over what seemed like an unpaved road,” Rashid told the Committee to Protect Journalists during an interview in Sulaymania shortly after the incident. Rashid said he was pulled from the truck, punched and kicked, and threatened at gunpoint to stop working or be killed. The assailants sped off, leaving Rashid bruised and shaken.

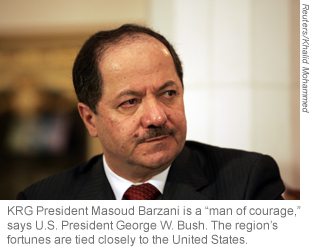

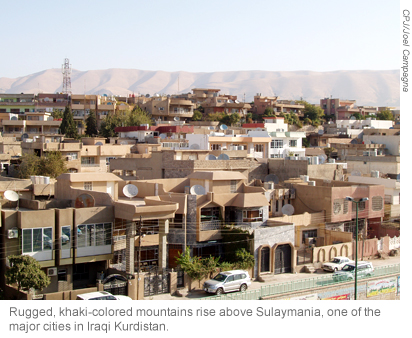

Iraqi Kurdistan, the mountainous region in the north of Iraq that is home to about 5 million people, has been recognized internationally for its tolerance of free expression. A small but combative independent press regularly challenges the region’s main political parties-Masoud Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Iraqi President Jalal Talabani’s Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)-by publishing daring stories about government corruption, mismanagement, social ills, and human rights abuses. The work of these print and online outlets has come to overshadow the well-funded and once-dominant media outlets run by the parties themselves.

In response, CPJ conducted a two-week fact-finding mission to Arbil and Sulaymania in October and November 2007, meeting with dozens of party-affiliated and independent journalists. In Arbil, seat of the KRG, officials and legislators said they were receptive to some of CPJ’s concerns and stressed that they were committed to a free press. But these officials were unable to account for the violent attacks on reporters, minimized the legal restrictions on the press, and lashed out at many independent papers and online publications, calling them scandal sheets. In addition, party leaders have barred their rank and file from speaking to the press without permission, and party-run newspapers regularly launch vitriolic attacks against independent journalists.

When asked about restrictions on the press, party and government officials shifted much of the blame to journalists. “We don’t claim we are perfect. …When in transition [to democracy] you have to pass through many stages,” Falah Bakir, head of the KRG’s Foreign Relations Department, told CPJ during a meeting in Arbil. “I believe that in Iraqi Kurdistan we are making steps forward. We want to have a free press, we want journalists to be respected and the voices of the people heard, but [journalists] lack professional experience.” Kawa Mawlud, editor-in-chief of the official PUK daily, Kurdistani Nuwe, put it more bluntly: “One of the shortcomings we see is not the limits on journalists, but that there is no limit.” The Iraqi Kurdish press is not without its flaws. Independent papers, which operate on shoestring budgets and have staff with little formal training, have relatively weak standards of professionalism, and their coverage has a heavy political bent. “After the uprisings, the Kurds didn’t have journalists. We had poets and writers, and they became journalists,” said Ako Mohamed, former editor of the Arbil-based weekly Media. “Newspapers … had no news. They were all opinion articles, and there was an ideology.” After enduring years of political repression and a 1988 campaign of genocide at the hands of Saddam Hussein’s government, Iraqi Kurds are regarded by many as the success story of Iraq. Benefiting from more than a decade and a half of de facto autonomy following the 1991 Gulf War, Iraqi Kurds boast a relatively stable government and an economy now in the midst of a development boom.Although the region has seen sporadic terrorist bombings-two targeting KRG and KDP offices in May 2007 claimed at least 45 lives-Iraqi Kurdistan has avoided the sustained violence of central and southern Iraq. KRG officials have aggressively promoted the area as the “Other Iraq,” hiring the powerful Washington lobbyist firm Barbour Griffith & Rogers, and stressing the region’s stability, business-friendly environment, and respect for human rights. “What is happening in the Kurdistan region-democracy, freedom of speech, economic development-is exactly what the world hoped for with the removal of the dictator. We are creating a stable democracy in the Middle East,” KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani declared in a glossy 2007 advertising supplement to the journal Foreign Affairs. “I do not understand why this is not acknowledged more often.” Certainly the KRG has a vested interest in willing the international community, especially the United States, to embrace the public image it has promoted. The KRG enjoys close relations with the U.S.; popular support for the United States and President George W. Bush runs uncommonly high thanks to the 2003 U.S. overthrow of Saddam Hussein, which the Kurds enthusiastically backed. During KRG President Barzani’s 2005 visit to the White House, Bush called him “a man of courage … who has stood up to a tyrant.” The Kurdish region hosts a U.S. military presence, and some U.S. political figures such as Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton have promoted the establishment of permanent U.S. bases here. The United States, which provided protection to the Kurds for more than a decade after the Gulf War, has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in humanitarian and development assistance. Now, the KRG has set out to attract new foreign investment and to develop international tourism and oil production. But tensions between the ruling parties and the independent press are likely to remain high in the near future. Despite its relative economic success, the region still suffers from high inflation, poor public services, economic disparities, and recurring allegations of government corruption-all fodder for a critical press corps. For all its shortcomings, the independent press has provided a crucial platform, giving voice to ordinary citizens and scrutinizing powerful politicians in an otherwise party-dominated media environment. The Kurds-whose homeland spans Turkey, Iran, Syria, and Iraq-make up one of the Middle East’s largest ethnic groups, numbering around 25 million, and represent the largest ethnic group in the world without a state. Like their regional brethren, Iraqi Kurds have suffered political betrayal at the hands of the West and political persecution at home.

A traditionally agricultural society that was underdeveloped under Saddam, Iraqi Kurdistan has since seen its population become more urban and its economy more reliant on construction, commerce, and government. Younger generations of Iraqi Kurds speak almost entirely Kurdish, eschewing the Arabic their fathers and mothers learned in Iraqi schools. Sentiment for Kurds to run their own affairs and to be separate from Iraq runs high. The Kurds’ newfound autonomy also transformed the media landscape. The KDP and PUK launched a new stable of media that included newspapers, radio, and television in Arabic and Kurdish. They offered fresh discourse opposing the Baathist regime and reflecting Kurdish aspirations. For most of a decade, the news media remained under the control of the ruling Kurdish political parties, reflecting party interests and avoiding criticism of party policies.

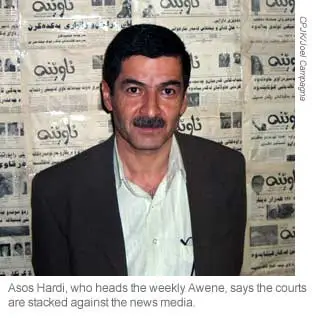

Since Hawlati’s launch, a handful of other independent and semi-independent papers have followed, most of them based in the comparatively liberal PUK enclave of eastern Iraqi Kurdistan. Awene, the region’s other leading independent paper with a circulation of about 15,000, publishes critical stories spotlighting corruption–such as an October investigation that accused a Kurdish businessman of pocketing $38 million in government money earmarked for army vehicle purchases. Other papers include the newly launched Rozhnama, a critical daily founded by Mustafa. New Radio is the region’s first non-party radio station; although it has received some KRG and U.S. aid, the station has aired critical programming. The most strident political criticism, however, is published in online magazines, among them the Sweden-based Kurdistanpost,which features opinion pieces and political satire from local writers and intellectuals in the Kurdish diaspora. Nabaz Goren, 29, a contributor to several newspapers including Hawlati and Awene, was abducted and assaulted in a manner strikingly similar to the October 2007 attack on Kurdistanpost‘s Rashid. Five Kalashnikov-wielding men wearing military uniforms forced Goren into a pickup truck as he left the Writers Union Club in downtown Arbil in April 2007. “They pulled a gun to my head and told me to get in,” Goren told CPJ at an Arbil café. Goren was blindfolded and driven for a half-hour before being dumped in a remote area, where he was beaten with a metal rod and rifle butts. As in the Rashid case, he was warned to stop working. “We are here to wise you up not to write,” one of the men said. “If you continue, we will continue.” Goren suffered a broken ankle, cracked teeth, and heavy bruising. Goren said he is unsure what triggered the assault but noted that he had published critical articles about several officials, including an article that mocked Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani’s official motorcades. “When the prime minister leaves his home, life stops!” he wrote. “Neither a citizen, nor a car, nor a bird, nor a breath can move so that His Highness … can pass.” In another article he accused President Masoud Barzani of being such a poor administrator that he “could not tie his own shoelaces.” Goren said he also argued with and wrote a critical article about a KDP media officer in the days leading up to the attack. Many journalists see an official hand behind the assaults. Aso Jamal Mukhtar, a 41-year-old cameraman, said he believes government retaliation was at work when assailants targeted him near Sulaymania’s Azadi Park in May 2007. Mukhtar, who works for Mustafa’s soon-to-be-launched Chaw TV and whose brother Kamal runs Kurdistanpost from Sweden, was assaulted by three men as he left the office of his former employer, the government-run Education TV. “It was dark and I found a car blocking my way,” Mukhtar said at a Sulaymania pizza parlor not far from the scene of the attack. “Three people with masks got out of the car quickly. Two had sticks in their hands and the third a pistol. They attacked the car and pulled me out.” He escaped with cuts and bruises. Mukhtar said PUK officials had complained to him on numerous occasions about Kurdistanpost, accusing him of writing for the site and insisting his brother stop critiquing Kurdish officials.

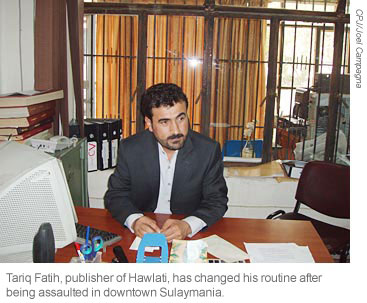

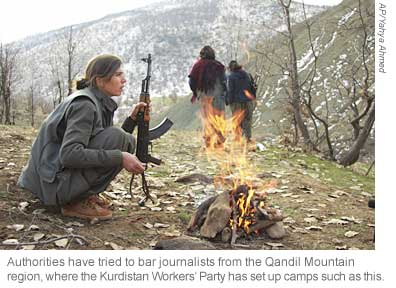

To an extent, the attacks and intimidation have accomplished their goal, leading some journalists to alter their work schedules to avoid being out at night. Tariq Fatih, 37, the publisher of Hawlati, said he began limiting his nighttime activities after being assaulted by several unknown men in a downtown Sulaymania restaurant. Twana Osman, former editor of Hawlati and now an adviser, said officials have passed along “friendly” advice to the paper, warning staffers to avoid going to clubs at night and to vary their travel routines. Amid recent tensions between Turkey and the Iraqi Kurdistan-based Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), security authorities have systematically barred journalists from the rebel stronghold in the Qandil Mountain area. Border skirmishes and Turkish shelling have been reported since late 2007, with Turkey launching an eight-day incursion into Iraqi Kurdistan in February. Some journalists attempting to cover the story were reportedly assaulted by these security forces. More routinely, police and security forces known as asayish have arbitrarily detained journalists or jailed them on court orders issued in connection with criminal defamation complaints. In other cases, security forces have harassed journalists covering public protests and confiscated their equipment, as was the case during 2006 antigovernment protests in the town of Halabja. Ahmed Mira, the youthful, clean-shaven editor of the investigative monthly Livin, runs his magazine from a small office on the top floor of a commercial building near Sulaymania’s bustling central market. Mira, a former school teacher, had his own run-in with asayish after his magazine ran a cover story speculating about President Jalal Talabani’s health and possible power struggles within the PUK over his succession. Headlined “Legacy of a Sick Man,” the article said Talabani’s purportedly declining health had caused political tensions “because there are many in the PUK waiting for zero hour in order to succeed Talabani.” The reaction was swift. Other prominent detentions include Hawlati writer Hawez Hawezi, who was arrested by security forces twice in 2006, the first time in March after he wrote an article referring to Barzani and Talabani as pharaohs who should leave the country if they cannot reform it. Two months later, he was detained again and held for several days after he wrote a piece describing his ordeal at the hands of security forces. His colleagues at Hawlati said he has since fled to Syria because of safety concerns. In November 2007, asayish agents detained Mosul-based reporter Faisal Ghazaleh of the PUK’s KurdSat TV. Ghazaleh said he was severely beaten with batons while interrogators made vague allegations that he had cooperated with terrorists by filming their attacks. A court ordered his release the following month after investigators failed to produce evidence of a crime, he said. “All those arrested were done so by laws that exist,” PUK media representative Azad Jundiyani, a harsh critic of the independent press, told CPJ. “We need to change the law and we will not have the problem of arresting journalists.” The laws cited by Jundiyani date back to the Baath era and enable government officials to harass, prosecute, and silence inconvenient independent journalists. After gaining de facto autonomy in 1991, Iraqi Kurds began repealing or replacing Iraqi laws deemed “incompatible with the welfare of the people,” but left intact the 1969 Penal Code and Code of Criminal Procedure. The penal code–which allows for pretrial detention and prison time for a wide range of expression-related “offenses”-has been used repeatedly by officials seeking to crack down on critical members of the press. Article 433, which criminalizes defamation and allows fines and imprisonment for offenders, is one of the most commonly used statutes. (Printing an offending comment in a newspaper is considered an aggravating circumstance.) Other articles of the penal code stipulate penalties for vague offenses such as publishing false information or insulting public servants, “the Arab community,” or a foreign country.

Since then, a rash of other criminal cases has targeted independent newspapers, particularlyHawlati. Just months after Qadir’s conviction, a criminal court in Sulaymania sentenced Twana Osman and Asos Hardi, the paper’s former editors, to six-month suspended jail terms for publishing an article alleging that KRG Deputy Prime Minister Omar Fatah ordered the dismissal of two telephone company employees after they cut his phone line for failing to pay a bill. Earlier, Hardi had been sentenced to a one-year suspended term for humiliating an aide to Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani by publishing an open letter from an artist who said the prime minister’s office never paid for artwork it took.

Hawlati says that at least 50 criminal complaints have been brought against it by government officials and citizens since its launch. Another case was added to the docket in January when Jalal Talabani launched a criminal lawsuit against the paper after it translated and reprinted excerpts from an article by U.S. scholar Michael Rubin of the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute. The article was highly critical of Talabani and Barzani, concluding that “the unreliability of [Iraqi Kurdistan] leadership makes any long-term U.S.-Kurdish alliance unwise.” What appears to have set off Talabani was Rubin’s assertion that the two leaders had amassed fortunes while in power. Concerns about the severity of the existing Baath-era media laws appeared, at least initially, to spur the KRG to craft more liberal legislation in 2007. In an eye-opening move, however, the KRG parliament in December significantly stiffened restrictions in the draft that had been under discussion for much of the year. The bill, which was published in the daily Rozhnama on January 6, stipulated fines between 3 million Iraqi dinars (US$2,450) and 10 million Iraqi dinars (US$8,200), and six-month newspaper suspensions for vague offenses such as disturbing security, “spreading fear,” or “encouraging terrorism.” Given the tenuous financial situation of independent papers-several operate at losses or barely break even-the elastic language of the bill could allow pro-party judges to put critical newspapers out of business. Similar fines were in order for those who “insult religious beliefs,” “tarnish common customs or morals,” or publish anything “related to the private life of an individual-even if it is true-if this insults him.” Parliament’s approval of the press bill triggered a storm of criticism from Iraqi Kurdish journalists and CPJ, leading President Barzani to veto the measure and send it back to parliament for revisions

“There is more pressure on us now,” said Rozhnama Editor Ednan Osman, citing not only the number of attacks but the aggressive tenor of government officials. “The political situation is complicated and the security situation is dangerous. These parties only want to hear their own opinions.” Iraqi Kurdish officials have argued that building a democratic society takes time and that missteps are inevitable. Yet the current trend appears to be toward a growing suppression of the press, which conflicts with the KRG’s lofty rhetoric of being the “Other Iraq” where stability and freedom abound. If Kurdish officials are serious about their public support for democracy and the rule of law, they should take a decisive stand against violent attacks on the press, put an end to spurious criminal prosecutions and the arrests of reporters, and do away with restrictive laws used to clamp down on the press. Parliament’s debate on the new press bill will be a good barometer of the government’s intentions. Joel Campagna is senior program coordinator responsible for the Middle East and North Africa at the Committee to Protect Journalists. |

|||

|

Recommendations to the Kurdistan Regional Government The Committee to Protect Journalists calls on Regional President and KDP head Masoud Barzani, Iraqi President and PUK head Jalal Talabani, Regional Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani, and the Kurdistan Regional Government to immediately adopt the following recommendations:

|

|||

But the increasing assertiveness of the independent press has triggered a spike in repression over the last three years, with the most forceful attacks targeting those who have reported critically on Barzani, Talabani, and other high-level officials, a CPJ investigation has found. At least three journalists have been seized and assaulted by suspected government agents or sympathizers, while a number of other reporters have been roughed up and harassed. To date, no one has been arrested for the attacks and officials of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), the semi-autonomous governing authority, have yet to provide answers. Critical journalists who have spoken out against Kurdish leaders have been detained by security forces and prosecuted under Baath-era criminal laws that prescribe steep penalties. In the past year, the KRG parliament has pushed for harsh new legislation that would set heavy new fines and allow the government to close newspapers.

But the increasing assertiveness of the independent press has triggered a spike in repression over the last three years, with the most forceful attacks targeting those who have reported critically on Barzani, Talabani, and other high-level officials, a CPJ investigation has found. At least three journalists have been seized and assaulted by suspected government agents or sympathizers, while a number of other reporters have been roughed up and harassed. To date, no one has been arrested for the attacks and officials of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), the semi-autonomous governing authority, have yet to provide answers. Critical journalists who have spoken out against Kurdish leaders have been detained by security forces and prosecuted under Baath-era criminal laws that prescribe steep penalties. In the past year, the KRG parliament has pushed for harsh new legislation that would set heavy new fines and allow the government to close newspapers. “When you face social and political problems you have two choices: You either make changes or you close the mouths of the journalists,” Nawshirwan Mustafa, a media owner and former PUK leader, told CPJ during an interview in his vast hilltop headquarters in Sulaymania. Mustafa, a charismatic and well-financed figure who split with the PUK to launch his own newspaper and television station, said he fears hard-line partyofficials have decided to pursue the latter course.

“When you face social and political problems you have two choices: You either make changes or you close the mouths of the journalists,” Nawshirwan Mustafa, a media owner and former PUK leader, told CPJ during an interview in his vast hilltop headquarters in Sulaymania. Mustafa, a charismatic and well-financed figure who split with the PUK to launch his own newspaper and television station, said he fears hard-line partyofficials have decided to pursue the latter course. Shortly after the 1991 Gulf War, Saddam’s army crushed an incipient revolt in Iraqi Kurdistan a month after it began. In April of that year, U.S. troops entered northern Iraq and established a safe haven over a large swath of the region in response to a humanitarian crisis triggered by the exodus of thousands of Kurds fleeing Saddam’s army into the mountains. Iraqi aircraft were barred from operating in a “no-fly” zone patrolled by U.S. and British fighters. By October 1991, Saddam decided to withdraw his army and government administration from much of the Kurdish region, ushering in de facto autonomy for Iraqi Kurdistan, which came under the control of Masoud Barzani’s KDP and Jalal Talabani’s PUK. The parties established a power-sharing agreement, and parliamentary elections were held in 1992.

Shortly after the 1991 Gulf War, Saddam’s army crushed an incipient revolt in Iraqi Kurdistan a month after it began. In April of that year, U.S. troops entered northern Iraq and established a safe haven over a large swath of the region in response to a humanitarian crisis triggered by the exodus of thousands of Kurds fleeing Saddam’s army into the mountains. Iraqi aircraft were barred from operating in a “no-fly” zone patrolled by U.S. and British fighters. By October 1991, Saddam decided to withdraw his army and government administration from much of the Kurdish region, ushering in de facto autonomy for Iraqi Kurdistan, which came under the control of Masoud Barzani’s KDP and Jalal Talabani’s PUK. The parties established a power-sharing agreement, and parliamentary elections were held in 1992. In 2000, after a period that saw a bloody war between the PUK and KDP followed by a truce, the region’s first independent newspaper, Hawlati(Citizen), was founded by a group of intellectuals from the PUK-dominated city of Sulaymania. Motivated by the absence of media that could hold the parties accountable, they launched the paper with a handful of staffers and a $3,000 investment. Hawlati quickly became the region’s most popular newspaper by casting for the first time in the local press a critical eye on the governing practices of the ruling parties. With a distinctly populist tone, its news and opinion pieces challenged the political domination of the parties, government nepotism, and the lack of public services. Today, the twice-weekly Hawlati is considered the most widely read newspaper in Iraqi Kurdistan with an estimated circulation of about 20,000.

In 2000, after a period that saw a bloody war between the PUK and KDP followed by a truce, the region’s first independent newspaper, Hawlati(Citizen), was founded by a group of intellectuals from the PUK-dominated city of Sulaymania. Motivated by the absence of media that could hold the parties accountable, they launched the paper with a handful of staffers and a $3,000 investment. Hawlati quickly became the region’s most popular newspaper by casting for the first time in the local press a critical eye on the governing practices of the ruling parties. With a distinctly populist tone, its news and opinion pieces challenged the political domination of the parties, government nepotism, and the lack of public services. Today, the twice-weekly Hawlati is considered the most widely read newspaper in Iraqi Kurdistan with an estimated circulation of about 20,000. Officials who spoke with CPJ denied responsibility for the attacks, saying, for example, that the military uniforms worn by the assailants are publicly available. In a written response to CPJ’s concerns in February, KRG foreign relations head Bakir said the attacks were under investigation. “Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani and all relevant authorities in the Kurdish region take these attacks seriously,” the letter said. “The protection of the right to free speech is a priority of this government.” He added: “It is my hope that the investigations will run their course and the perpetrators brought to justice.”

Officials who spoke with CPJ denied responsibility for the attacks, saying, for example, that the military uniforms worn by the assailants are publicly available. In a written response to CPJ’s concerns in February, KRG foreign relations head Bakir said the attacks were under investigation. “Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani and all relevant authorities in the Kurdish region take these attacks seriously,” the letter said. “The protection of the right to free speech is a priority of this government.” He added: “It is my hope that the investigations will run their course and the perpetrators brought to justice.”

KRG courts are packed with loyalist judges who have predictably handed down harsh verdicts against journalists, according to CPJ’s analysis.”Judges are appointed by the parties,” said Asos Hardi, a former Hawlati editor who now heads the weekly Awene. “So you can imagine it is very hard for them to make an independent decision when one of the parties is involved.” The December 2005 court proceedings against the online writer Qadir were notoriously unfair; he was convicted and sentenced in a hearing that lasted less than an hour.

KRG courts are packed with loyalist judges who have predictably handed down harsh verdicts against journalists, according to CPJ’s analysis.”Judges are appointed by the parties,” said Asos Hardi, a former Hawlati editor who now heads the weekly Awene. “So you can imagine it is very hard for them to make an independent decision when one of the parties is involved.” The December 2005 court proceedings against the online writer Qadir were notoriously unfair; he was convicted and sentenced in a hearing that lasted less than an hour.