Caracas, Venezuela, January 12, 2007—A joint delegation of the Committee to Protect Journalists and Instituto Prensa y Sociedad (IPYS) said today it is alarmed about the lack of transparency in President Hugo Chávez Frias’ decision not to renew the broadcast concession of the privately owned television station RCTV.

This week, as Chávez was inaugurated for his third term, the delegation examined the highly polarized press conditions in Venezuela. Administration officials said they pride themselves on promoting free expression in the context of what they call “socialism of the 21st century.” But journalists told the delegation that the government punishes critical news outlets by, among other things, blocking access to government events and officials, withholding public advertising, filing criminal defamation complaints, and imposing content restrictions.

The dispute over RCTV’s broadcast concession has come to the forefront. In public comments made before and after his inaugural on Wednesday, Chávez said that his administration would not renew RCTV’s concession, which the government said expires on May 28. Administration officials, who say the government has the right to allocate frequencies in the manner it sees fit, have made broad allegations that the station has violated the law. RCTV disputes the government’s assertions and claims that the Chávez administration is simply suppressing critical coverage. RCTV, founded in 1953, is known for its ardent opposition views.

The CPJ-IPYS delegation met with members of private and state-owned media, government officials, media executives, press freedom advocates, lawyers, and scholars during its weeklong investigation. CPJ is a New York-based nongovernmental organization that seeks to promote press freedom worldwide, while IPYS is a regional press freedom group based in Lima, Peru. The delegation included CPJ board member Victor Navasky, a prominent U.S. journalist and publisher emeritus of The Nation magazine; CPJ Americas Program Coordinator Carlos Lauría; CPJ consultant Sauro González Rodríguez; IPYS Executive Director Ricardo Uceda; and IPYS-Venezuela Director Ewald Scharfenberg.

“Despite our meetings with high-ranking government officials, the standards and procedures for concession renewal are ambiguous,” Lauría said. “We urge the government to clearly explain the criteria, to conduct fair reviews based on those criteria, and to give broadcasters the opportunity to present their case in a neutral venue.”

Added Uceda: “We understand the government has the right to assign broadcast frequencies, but this function must be based on clear rules and transparent procedures.”

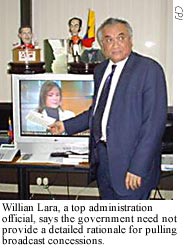

In a meeting with the delegation, Minister of Communication and Information Willian Lara said the RCTV decision was not a politically inspired act of retaliation. Lara said the government did not have to provide a detailed legal rationale because it wasn’t revoking the concession, simply applying a 1987 decree that sets a 20-year term for broadcast concessions.

Lara said RCTV had violated the Law of Social Responsibility in Radio and Television by running, for example, sexually suggestive programming during daytime hours. The social responsibility law, passed in 2004, has been widely criticized by press freedom advocates for its broad and vaguely worded restrictions on free expression. Article 29, for example, bars television and radio stations from broadcasting messages that “promote, defend, or incite breaches of public order” or “are contrary to the security of the nation.”

Other government officials have offered a variety of broad allegations: that RCTV attempted to destabilize the Venezuelan government, that it violated journalistic ethics, and that it participated in the April 2002 coup. José Vicente Rangel, who served as Chávez’s vice president until this week, said the National Telecommunications Commission (CONATEL), the agency in charge of broadcast concessions, had compiled a detailed file of RCTV violations and had followed protocol in reaching a decision.

The delegation sought to review CONATEL’s file, but agency officials did not immediately comply with the request. “We have tried to find evidence that the government followed a clear administrative procedure but we haven’t been able to corroborate the administration’s claim that its decision was based on strict application of the law,” Uceda said.

RCTV has pressed a number of arguments in favor of its concession renewal. Station President Marcel Granier said CONATEL failed to respond to RCTV’s formal request for renewal, as required by law, and thus the concession should automatically roll over. RCTV said it was given no opportunity to respond to the government’s allegations or to make its case for renewal. The station also argues that, under its interpretation of the law, the concession runs until 2022.

The CPJ-IPYS delegation said the absence of explicit criteria for renewal could have implications for other broadcasters.

“I take seriously the government’s talk of the need for diversity of media ownership and the desirability of encouraging cooperatives, small community-owned stations, and experiments in public-private ownership. But I think you can’t achieve that and avoid the appearance of inappropriate politics without a transparent process,” CPJ board member Navasky said. “Although we don’t underestimate the frustrations of dealing with hostile media, we respectfully urge the government to be more committed to the requirements of free expression.”

CPJ and IPYS research shows that the Venezuelan government has enacted numerous restraints against the press in the past two years. In January 2005, the National Assembly drastically increased criminal penalties for defamation and slander while expanding the number of government officials protected by desacato provisions, which criminalize expressions deemed offensive to public officials and state institutions. The social responsibility law, signed in 2004, took effect in 2005.