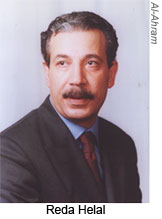

Reda Helal vanished in central Cairo four years ago. Now, even the memory of the prominent state editor has nearly disappeared. Why have the government and the press ignored his case?

CAIRO, Egypt

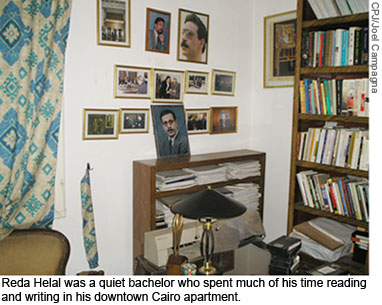

The dimly lit fifth-floor apartment at 34 Ismail Siri St. in downtown Cairo looks almost exactly the way it did four years ago when Reda Helal last set foot in it. The towering bookshelves that line the living room and adjacent office still brim with Arabic and English titles on politics, economics, and religion. A laptop computer rests on the large wooden desk, awaiting its next use.

Despite appearances, Helal, a senior editor at Egypt’s leading daily, the Arabic-language Al-Ahram, seems no closer to returning home than he did on the sweltering summer day of August 11, 2003. That afternoon, Helal was said to have headed home from a routine day at Al-Ahram. And then he simply vanished. No one has heard from him since, and there are few clues as to his fate.

Despite appearances, Helal, a senior editor at Egypt’s leading daily, the Arabic-language Al-Ahram, seems no closer to returning home than he did on the sweltering summer day of August 11, 2003. That afternoon, Helal was said to have headed home from a routine day at Al-Ahram. And then he simply vanished. No one has heard from him since, and there are few clues as to his fate.

“The way he disappeared is baffling,” said Wael Abrashi, editor of the independent weekly Sawt al-Umma, who has followed Helal’s case. “It’s as if the earth suddenly gaped open and swallowed him.”

Despite Egypt’s shoddy human rights and press freedom record, the “enforced disappearance” or murder of a journalist is rare. One involving senior staff at a prominent, pro-government paper such as Al-Ahram–its chief editor is appointed by President Hosni Mubarak–is unheard of. Helal’s family and a few journalists have searched for answers to no avail, and Egypt’s vast security apparatus claims it hasn’t been able to crack the case. The near-total absence of information about his fate has perplexed and unsettled Egyptian journalists.

Joel Campagna tells the backstory of this report in an AUDIO SLIDE SHOW. |

Equally perplexing has been the silence from Helal’s professional colleagues, who have largely ignored his plight over the last four years–a situation perhaps explained by Helal’s unpopular pro-American views, his support of relations with Israel, and by a degree of fear. His own newspaper, Al-Ahram, one of the largest and best known newspapers in the Arab world, has barely published a word about him in three years. In Egypt, and in the region at large, he is a forgotten man.

Irrespective of what happened to Reda Helal and who may have been behind his strange disappearance, his family and a handful of journalists and rights activists are troubled by the Egyptian government’s failure to shed light on the case.

“The responsibility of the mysterious disappearance of our colleague Reda Helal rests on the shoulders of the state and the government,” said Gamal Fahmy, an Egyptian columnist and board member of the Egyptian Journalists Syndicate. “This terrible silence has been going on for years, and it can only make people more suspicious.”

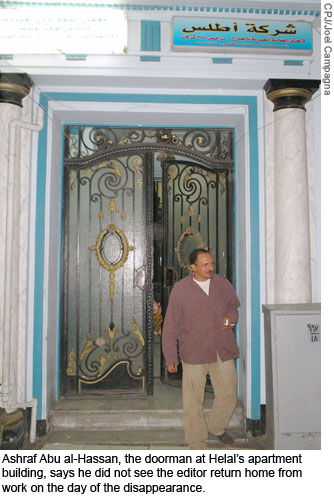

By all accounts, Monday, August 11, 2003, began routinely for Helal. In the early morning, the doorman at the apartment building where Helal had lived alone for five years fetched him the morning newspapers and a pack of cigarettes, just as he did every day. Helal, 45, had been suffering from a bad cold; he later ordered a glass of fresh-squeezed orange juice, which the doorman also delivered to his door. Helal left for work before 10 a.m., probably catching a taxi on busy Qasr al-Aini Street, just around the corner from his flat.

Helal spent the next several hours at Al-Ahram‘s offices on Gala’ Street in downtown Cairo, according to reports in Al-Ahram and other papers. Before leaving the office in mid-afternoon, he ordered lunch, as he often did, from Abu Shaqra, the well-known kebab restaurant located a few dozen yards from his apartment building. At around 2:40 p.m., according to Al-Ahram‘s published account, a driver working for the newspaper drove Helal to his apartment and supposedly dropped him off at the entrance.

It was the last time anyone reported seeing him.

When a deliveryman from Abu Shaqra arrived with Helal’s lunch at about 3:30 p.m. there was no answer at his apartment, and the door, according to published accounts, was padlocked–something the journalist normally did during absences of several hours or more. It took two days before colleagues and family realized something was amiss.

When a deliveryman from Abu Shaqra arrived with Helal’s lunch at about 3:30 p.m. there was no answer at his apartment, and the door, according to published accounts, was padlocked–something the journalist normally did during absences of several hours or more. It took two days before colleagues and family realized something was amiss.

On August 13, colleagues began to wonder why Helal had not shown up for work; he had been charged with seeing that day’s paper to press. “Al-Ahram called me and asked if Reda was with me, and I said no,” Helal’s 43-year-old brother, Sayed, told CPJ. “I asked why and they said he didn’t come to the office.” Sayed, who lives in the Nile Delta city of Mansoura, rushed to Cairo with his nephew Maher. When they arrived, the doorman helped them break the padlock and enter the apartment, which showed no signs of foul play. The only aberrations seemed to be the windows oddly left open in the reception room and the fax and answering machines that were unplugged.

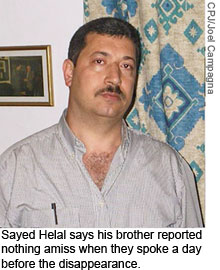

Sayed said he had spoken to his brother only a day before the disappearance and had picked up nothing unusual. He reported his brother missing to the nearby Sayeda Zeinab police station.

Egyptian police and security forces launched what Al-Ahram described as an “intensive” and “high-level” search for the missing editor. Investigators reportedly combed Helal’s apartment for clues and questioned his friends and colleagues. Throughout their investigation, Egyptian security officials have remained tight-lipped, although Al-Ahram offered a glowing account of their early work on the case. “The security investigation team headed by Habib al-Adly, the interior minister himself, and comprising 300 officers has not left a single thread, whether political or criminal, local or international, without tracking it down,” the newspaper reported on August 23, 2003. “But such apparatuses usually work in a secretive and discreet manner … since they believe that what really matters is the conclusions and that announcements may give rise to gossip defaming the innocent.”

In the weeks after Helal disappeared, security officials were quoted as saying that they believed the case was not political, that it could be related to a personal matter, and that they were following a number of leads. The state-backed daily Al-Akhbar published transcripts of voice messages allegedly left on Helal’s answering machine, including several from women, one of whom reminded Helal about an upcoming party being hosted by the U.S. ambassador. But after several months, Sayed Helal was told the investigation was at a standstill, and that it would go forward only if there were new leads.

In the weeks after Helal disappeared, security officials were quoted as saying that they believed the case was not political, that it could be related to a personal matter, and that they were following a number of leads. The state-backed daily Al-Akhbar published transcripts of voice messages allegedly left on Helal’s answering machine, including several from women, one of whom reminded Helal about an upcoming party being hosted by the U.S. ambassador. But after several months, Sayed Helal was told the investigation was at a standstill, and that it would go forward only if there were new leads.

“We only got speculation and hints released by security sources,” said Hafez Abu Seada, secretary-general of the Egyptian Organization for Human Rights (EOHR). “They claimed that some of Helal’s private relations might have something to do with his disappearance. They first spoke about so-called ‘relations with women,’ then they took refuge in silence.”

Egyptian tabloids and pan-Arab newspapers occasionally published dubious, unsubstantiated reports that Helal was seen abroad, that he was in Israel, or that he had been seized by the security apparatus of an unnamed country because of a supposed big scoop he was about to publish. The most widely reported development emerged in July 2005, when the Egyptian Islamic Jihad stated it had killed Helal, a noted critic of Islamic extremism, shortly after abducting him. The claim was buried in a threatening e-mail sent to Egyptian secular writer Sayyed al-Qimni informing him that he would meet the same fate as Helal, whom the group “brought down by bullets.” With few exceptions, journalists, human rights activists, and influential Islamists have discounted the claim’s authenticity, noting that the e-mail was sent long after the disappearance and that Helal, though a tough critic, was not regarded as a top enemy of militants.

Four years on, Egyptian authorities have yet to release details of their investigation, and the case has been essentially forgotten.

“There are lots of contradictions and discrepancies between the different stories about Helal’s disappearance,” said EOHR’s Seada. “There is no clear evidence that he returned to his apartment from work. According to one story, he made it to a neighboring country. …We have not seen, so far, any serious case scenario.”

“There are lots of contradictions and discrepancies between the different stories about Helal’s disappearance,” said EOHR’s Seada. “There is no clear evidence that he returned to his apartment from work. According to one story, he made it to a neighboring country. …We have not seen, so far, any serious case scenario.”

CPJ made repeated requests to meet with officials from the interior and information ministries in Cairo to discuss the case. Those requests, placed through the Egyptian embassy in Washington, were ignored. “The government is continuing its investigation into the case of Reda Helal,” an embassy spokesman told CPJ in August. “So far, that investigation has not produced any significant information regarding his disappearance. However, this is a case that the government is pursuing very seriously, and when the investigation produces any relevant information, the government will make it public.”

A few anomalies in the case raise questions. Although Al-Ahram has reported that its driver dropped off Helal at his apartment building the day he disappeared, there are apparently no corroborating witnesses. Ashraf Abu al-Hassan, the building’s doorman for 10 years, told CPJ that he was on duty the day Helal went missing and never saw the editor return that afternoon. Neither he nor frequent customers at the Zouzou café next door reported seeing any unusual activity that day. Attempts by CPJ to locate the driver, identified as Sayed Abdel Ati, were unsuccessful. Sayed Helal said Al-Ahram rebuffed his requests to speak directly with the driver.

Al-Ahram‘s chief editor, Osama Saraya, did not respond to CPJ’s repeated requests for an interview. In early September, an Al-Ahram secretary told CPJ that Saraya was prepared to comment, but the editor did not respond to CPJ’s subsequent e-mailed questions.

Sayed Helal, for one, believes his brother never reached the apartment building, and that he disappeared on his way home from work.

For all his unpopular political views, Reda Helal was not the sort of crusading journalist one would expect to be in danger because of his work, according to his family and colleagues. A career pro-government journalist, he joined Al-Ahram in the mid-1980s and subsequently wrote for other Arabic-language newspapers. In the early 1990s he spent time in New York as correspondent for the newspaper Al-Alam al-Youm and later returned to Egypt to join the upper echelons of Egyptian state media, where he was promoted to deputy editor–a post that effectively made him gatekeeper of what could and could not appear in Al-Ahram‘s pages. He wrote a weekly column and was a prolific author, publishing several books on economics, U.S. politics, Islam, and U.S.-Islamic relations.

At Al-Ahram, colleagues described Helal as a factotum of then-chief editor Ibrahim Nafia, someone who would do Nafia’s bidding at the Egyptian Journalists Syndicate. There, he was known to challenge independent journalists and to support government sympathizers in syndicate elections.

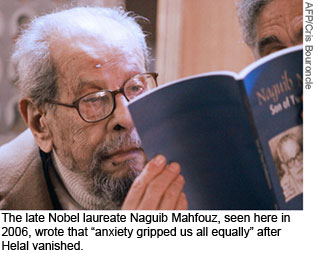

Friends and neighbors describe Helal as a quiet bachelor with a self-deprecating wit, a private man who spent long hours in his apartment reading and writing. Like many journalists, he had a large network of professional contacts, ranging from the U.S. Ambassador C. David Welch to Naguib Mahfouz, the Nobel Prize winner in literature whose weekly salons in the Cairo neighborhood of Garden City were frequented by Helal.

Friends and neighbors describe Helal as a quiet bachelor with a self-deprecating wit, a private man who spent long hours in his apartment reading and writing. Like many journalists, he had a large network of professional contacts, ranging from the U.S. Ambassador C. David Welch to Naguib Mahfouz, the Nobel Prize winner in literature whose weekly salons in the Cairo neighborhood of Garden City were frequented by Helal.

In the pages of Al-Ahram, Helal was known as a liberal writer critical of Arab nationalist thought and militant Islam. Unlike most Egyptian columnists, he supported the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq and was a strong backer of Egypt-Israel relations. As a result, Helal’s writings earned him few admirers among the country’s nationalist-oriented press. “Reda was virtually the only ‘liberal’ writer of such stature in Egypt–a highly placed editor and prominent columnist in the regime’s flagship daily,” said Raymond Stock, Mahfouz’s biographer and a friend of Helal. “He constantly attacked the Islamists, though he also stood out against virtually the entire trend of anti-Western thought that dominates the secular opposition here, too.”

After the September 11 attacks on the United States, Helal admonished those who rationalized terrorism, calling them the “Bin Lakins”–a play on the Arabic word lakin, or “but”–for only mildly condemning Osama bin Laden with caveats. Helal also criticized nationalist and Islamist discourse, which he blamed for the Arab world’s lack of democracy, among other ills, and Arab intellectuals who sympathized with deniers of the Holocaust. “It is not in our interest to deny the Holocaust, because we are not responsible for it, and we should not sympathize with those who should be blamed for it,” he told the Al-Ahram Weekly in 2000.

In his last column for Al-Ahram–published the day before he disappeared, under the headline “The Crisis of Democracy in the Arab World”–Helal criticized recent elections within the Egyptian Journalists Syndicate. Using the elections to draw a broader critique of democracy in the Arab world, he wrote that even free and fair elections can bring to power “non-democrats, whether they are Islamists or fascist nationalists.”

Still, his commentaries offer few clues about who may have targeted him. “I don’t think his politics played a role in this,” said brother Sayed, echoing a sentiment widely held by journalists. While his political positions may have generated some animosity, he said, Helal reported no threats and had no obvious enemies.

“The strange thing is that he had good will with key persons in power in Egypt,” remarked Al-Ahram reporter Karem Yahya. “He was not an opponent of Mubarak or an opposition figure. His political views [such as calling for normalization of relations with Israel and supporting certain U.S. policies] were being discussed in official circles, even if they were widely criticized.”

Many journalists agree that Helal’s disappearance was skillfully enacted. “The feeling is that whoever did it was professional,” said Yahya, who suggested foreign intelligence agents were behind the disappearance. Others said the job was done closer to home.

According to the Egyptian Organization for Human Rights, 53 people have disappeared in Egypt between 1992 and 2006, many of them suspected Islamist militants. The Helal mystery brings to mind another high-profile case from more than a decade ago. On December 10, 1993, Libyan dissident Mansour Kikhia vanished from his hotel while in Cairo to attend a human rights conference. At the time, speculation was rife that he had been seized by Libyan agents, but, as in Helal’s case, there was little evidence to go on.

It would later emerge that Kikhia was seen leaving his hotel with two men claiming to be Egyptian security agents, and drove away with them in a car whose license plates bore the markings of Egyptian security. U.S. officials, investigating because Kikhia’s wife was a U.S. citizen, told The Washington Post in September 1997 that Egyptian agents had carried out the abduction and Kikhia was transferred to Libya, where he was secretly executed in 1994. An infuriated Mubarak denied involvement. The Egyptian government’s investigation remains under wraps.

Whatever role Egyptian security may or may not have played in Helal’s disappearance, many observers find it difficult to believe that the authorities have no information about the editor’s fate. Egypt’s multilayered security apparatus is among the most sophisticated and omnipresent in the region, employing thousands of agents and informants. The area where Helal was said to have gone missing is regarded as one of the most secure in the entire city.

“We have submitted a number of requests to the public prosecutor to keep us informed about the outcome of the investigation, but so far, there is no response,” columnist Fahmy said. “We cannot believe that the ubiquitous and swelling security services have no explanation and cannot provide us with an answer.”

“There was no serious investigation at all,” said the EOHR’s Abu Seada. “No statement about serious efforts to find out how he disappeared and where he was held and why he was abducted was made public. We only got speculation and hints released by security sources.”

Nearly as troubling as the Egyptian government’s silence has been that of Egypt’s normally combative press. Al-Ahram and other newspapers closely reported Helal’s disappearance for several weeks in late summer 2003. By the following January, coverage had all but stopped, and public expressions of solidarity by journalists were nonexistent.

“The response to Reda is weak and shameful,” said Yahya, the Al-Ahram journalist who is also co-founder of a small group within the Egyptian Journalists Syndicate called Journalists for Change.

Journalists attribute the press’s indifference to Helal’s political positions and the political currents of nationalism and Islamism that dominate Egypt’s Press Syndicate, which had little sympathy for Helal’s views. But some journalists contend that fear has also played a role, and that journalists, especially at Al-Ahram, are simply frightened to take on a case that has the markings of an enforced disappearance directed by security services.

“Maybe he is not so popular because of his politics,” Yahya said. “But I think this is secondary. I think people here are scared, especially with the mysterious circumstances.”

Finally, in September 2006, the press freedom committee of the Egyptian Journalists Syndicate organized an event spotlighting the Helal case and calling on the authorities to reveal information about their investigation. During the event, which was attended by CPJ, several journalists apologized to Helal’s brothers for their long and strange silence on the case. Conspicuously absent were participants from Al-Ahram.

Finally, in September 2006, the press freedom committee of the Egyptian Journalists Syndicate organized an event spotlighting the Helal case and calling on the authorities to reveal information about their investigation. During the event, which was attended by CPJ, several journalists apologized to Helal’s brothers for their long and strange silence on the case. Conspicuously absent were participants from Al-Ahram.

“The negligence on the part of the journalists is obvious,” noted Wael Abrashi. “But it’s much more obvious,” he added, as far as Helal’s Al-Ahram colleagues are concerned.

On August 11, 2007, the silence continued as the fourth anniversary of Helal’s disappearance passed largely unnoticed. Before his death, Nobel laureate Mahfouz wrote a short, dream-like narrative about a missing man, whom biographer Stock identified as Helal. In “Dream 151”–included in the compilation Dreams of Departure translated by Stock–the author writes: “Under the tree we would sit with him, for evenings of both enjoyment and of learning, when once he excused himself in order to take his medicine. He went up to his flat–but didn’t come back. When one of us went to check on him, he found the apartment locked up tight from the outside. So began a fruitless search for him in all his haunts, as anxiety gripped us all equally–those who loved him, and those who hated him, and those who were indifferent to him, as well. Meanwhile, at our mosque, the imam led the Prayer for the Absent on the soul of the one who was no longer seen.”

Joel Campagna is CPJ’s senior program coordinator responsible for the Middle East and North Africa. Kamel Labidi, CPJ’s regional representative in the Middle East, contributed to this report.