Vidya Krishnan, a freelance reporter who has covered healthcare in India for 17 years, says she has never seen the kind of harassment and threats that health reporters have received while covering COVID-19.

Krishnan has been reporting on the disease since February, and has highlighted the government’s failure to stockpile protective equipment for health workers. In response, government officials have called her reporting “fake news,” and she has been relentlessly harassed online.

Krishnan was formerly the health editor of The Hindu newspaper, and her first book is set to be published next year, on tuberculosis.

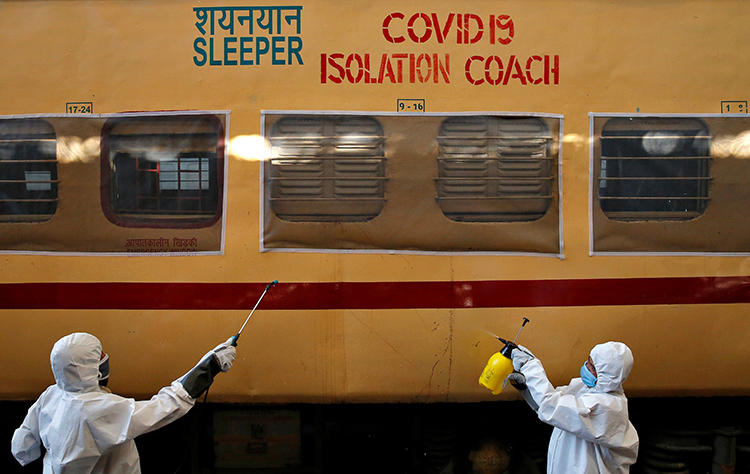

India has instituted a three-week nation-wide lockdown to combat the virus, one of the harshest in the world, according to news reports. According to the World Health Organization, there were 4,067 confirmed COVID-19 cases in the country as of April 7.

Krishnan spoke with CPJ in a phone interview on April 3. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How did you get started in health reporting?

I came to the beat because, in Indian newsrooms, health is a softer beat. Men get the “manlier” beats like national security and politics and all of the lucrative beats, so if you notice in India, most of the health reporters are women. Tangentially, that is the reason now—when there’s so much pressure on science reporters—that women are being trolled, abused, and threatened.

In my 17, almost 18 years of reporting on health, I’ve never seen anything like this. I’ve been called unpatriotic, I’ve been called a traitor, people are asking for me to be arrested immediately for spreading fake news.

Why do you think gendered attacks have increased amid the pandemic?

What is happening now is an amalgamation of patriarchy, of Indian society not being used to authoritative voices which are all female. Indian society kind of expects women to softball a bit, and I genuinely believe one of the reasons that we can finally get our government to start acting on PPE [personal protective equipment] and the shortages is purely because of the unflinching reporting that has been going on over the past two months.

How has reporting on this pandemic been different from other health coverage?

Like everyone says, this is unprecedented for the whole world. But I’m taken aback by how much we do not want to listen to the facts if they are not pleasant. Critical news is not fake news, but that’s the label that’s being given; that you’re either a Muslim sympathizer, spreading fake news, or in my case: there are very graphic photographs of me on social media, of me on a leash like a dog and [Chinese President] Xi Jinping holding the leash and it’s like, “China has funded these critical reporters.”

The government’s current [COVID-19] policy is a national security threat. It’s one of these infectious diseases where no one is safe unless everyone is safe.

It becomes political, and nobody is understanding that doctors are going to go out and die. And once the doctors die, there is no one to save the rest of us.

We’re all at risk, our families are at risk, but even then, nobody wants to hear anything against the [Bharatiya Janata Party]. The most shocking thing is that every other leader in the world is taking press briefings every day—but neither the Indian prime minister, nor the Indian health minister, nor the Indian health secretary has yet to come in front of the media.

This pandemic is coming after six years of the [Narendra] Modi administration tilling the ground and making it completely fertile for unscientific thinking, for promoting cow dung and cow urine and magical remedies and homeopathy as cures.

I’m worried about how the government has responded, particularly the climate it has created of unscientific thinking, of completely holding scientists and researchers in contempt, not investing money in health sector, and now, we are facing something like this and we have no trust in the system and our “magical thinking” is not going to save us. And the messengers of bad news, which are the health reporters, are the ones who are facing the flack for delivering the bad news.

How are you keeping yourself and your sources safe?

I try to base [my reporting] on documents so I don’t pin it on people.

One of the things that I’m genuinely concerned about is the threats in my inbox. I don’t have a correct threat perception for it, because an email is just an email, but then I know from experience and from having common friends with Gauri Lankesh, that she used to get a lot of hate like that, up until someone showed up at her home one day and shot her. I constantly tell myself that’s not going to happen, but that is in my head.

Every time a story is about to go online, I do wonder about judicial harassment because India has invoked this colonial legislation called the Epidemic Diseases Act, which was British-era law during the bubonic plague of 1897, and under that law they anyone, whoever they consider as fake news, can be charged with sedition, can be charged with fueling panic amongst the community, and be jailed. It gives the government sweeping powers and we’ve already seen they’ve gone after The Wire.

I was already worried, but last week the central government went to the Supreme Court requesting media to only report what is vetted by government. But the most frustrating part is when I do reach out to the government for responses, they don’t get back in time to answer and at press briefings they don’t take questions from critical journalists. So how am I supposed to get a version from them when they’re just not putting anything out and not taking questions from critical journalists?

I frankly don’t know how to report at this point and I’m struggling. This is new territory, so you learn how to report with every story.

Have authorities provided adequate information on the virus?

More disturbing for me is that the government has not been transparent. They have two websites—the Health Ministry and the Indian Council of Medical Research—and they’re both working together on the pandemic response. Last week, both websites were putting out different data on the number of infected cases, the number of tested cases, and deaths.

When journalists brought up the difference between these two—the ICMR was putting out a higher number than the Health Ministry—they [the ICMR] just stopped putting the numbers out.

I think the testing figures are a conservative estimate. I definitely think that every data point that’s put out by the Health Ministry: firstly, it’s updated once in two days, and even when it is, it’s a huge underestimation. We are working blind, we don’t have data we can rely on from the government, we definitely don’t have statements we can rely on from the government.

We’re under the world’s harshest lockdown right now and repeatedly the government has said the citizens have to do their responsibility without saying what [the government] is going to do.

Do you have concerns about how the Disaster Management Act, which criminalizes the “act of creating panic,” and the Epidemic Diseases Act are being used?

Absolutely, that’s the whole purpose of [the Disaster Management Act and Epidemic Diseases Act].

Most of my beat colleagues who work for conservative newsrooms, they don’t have the freedom or the years of experience to say “I’m going to do this,” and they have editors who don’t understand the technical beat, and they don’t want to stick their necks out, and then [editors] don’t trust the expertise of the female reporters.

So, a lot of mainstream media, even well-meaning newsrooms, are self-censoring. There’s a very huge sense of self-doubt even when they have all the information. Nobody wants to mess with this government.

Then there is a media gag [the Supreme Court directive for outlets to refer to and publish the official government version], and then doctors have been threatened that they will lose their jobs if they complain about a lack of safety kits. They’re muzzling not just journalists, they’re muzzling people in the health sector who are having to go out and work in hospitals that don’t have enough kits or ventilators or people.

How has the pandemic affected your sourcing?

One of the things that’s coming to haunt this government is that six years ago, one of the first things they did was ban NGOs that receive foreign funding. A lot of public health policy think tanks were gutted, the NGO sector was completely gutted.

And, systematically over six years, the voices in civil society and the voices in the health sector—scientists and health experts aren’t exactly rabble-rousers to begin with—realized the atmosphere is just not suitable to go on record. So Indian-origin doctors and scientists and researchers from outside are still talking, but people within India are worried and very understandably so, because the government goes after them for licenses, cuts their funding, and bleeds them dry.

My challenge is the older, senior doctors aren’t speaking to media, but the younger doctors, who have to go out and care for people without safety kits, are so angry that they’re willing to share information, if not put their name out there. And in that gap is a lot of where my reporting is coming out of.

I don’t use a lot of anonymous sources because you just can get into so much trouble with the media gag and the Epidemics Act so it’s not even worth it. So, stories do take longer, but that’s the only way.

What have been the biggest challenges during this time?

The biggest challenge in front of me is the government verifiably lying. Midway through March they entirely denied the lack of an equipment stockpile—but now they routinely say in the press conferences that yes, we had some shortage issues and have floated new tenders. Meanwhile, in the press conference they used the term “fake news” for Caravan’s reporting, and that unleashed trolls against reporters after the stockpiling story came out.

What do you and other journalists need in order to be able to report freely?

Two things come to mind – one is that my government needs to stop intimidating journalists; it needs to take questions, and not just from their favorite channels.

The second thing is that I’m worried about is the lack of global voices speaking out. This is one of those diseases where we’re all in it together. The pandemic is moving south, and the future course of the pandemic will be decided in the global south. What worries me the most that is that the homeopathy stuff has been allowed to go on for as long as it did, and that countries aren’t being told to test more, more directly. There is no comment on countries that aren’t doing very well, even when journalists reach out and say our government is stonewalling.

I really wish [the World Health Organization] spoke out more. This is happening in a bunch of countries and I feel like there are lots of journalists out there on their own with no one trusting their words, their expertise, and the experts are not wanting to stick their necks out, and it’s a frustrating situation to be in.

CPJ emailed the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and the Ministry of Home Affairs for comment, but did not receive any responses.

CPJ’s safety advisory for journalists covering the coronavirus outbreak is available in English and dozens of other languages. Additional CPJ coverage of the coronavirus can be found here.