Like the death of a loved one.

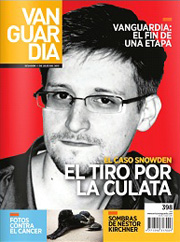

That’s how Juan Carlos Calderón, editor of the newsmagazine Vanguardia, described the June 28 closing of the newsweekly that for eight years published hard-hitting investigations about public officials and faced frequent government harassment. Yet the final days of Vanguardia were almost as controversial as its stories.

The editorial staff publicly criticized ownership’s decision to shutter the newsweekly in the wake of the June 14 passage of a restrictive new communications law. President Rafael Correa alleged that Vanguardia‘s demise stemmed from irresponsible journalism and cratering circulation. Amid confusion, labor disputes, and a last-minute order to stop the presses, the final edition was published online rather than in print on July 1.

Vanguardia‘s closure was a huge blow for Ecuadorian journalism, Mauricio Alarcón, director of projects for the Quito-based press freedom organization Fundamedios, told CPJ. He described Vanguardia as the only print media outlet in Ecuador dedicated to investigative journalism. Recent high-impact stories examined allegations of corruption against former Central Bank President Pedro Delgado, a cousin of Correa who has since fled to Miami, as well as government oil sales to China that had been shrouded in mystery.

But the magazine has paid a steep price for its critical reporting of the Correa administration, which has led Ecuador into a new era of media repression by pre-empting private news broadcasts, enacting restrictive legal measures, smearing critics, and filing debilitating defamation lawsuits, according to CPJ research.

In apparent reprisal for its investigations, police raided Vanguardia‘s offices in 2010. Authorities have confiscated the magazine’s equipment on three occasions, as well as its archives, and the ownership was hit with government fines as well as tax investigations.

“There is not a single government entity that did not collaborate in this persecution,” the magazine said in its farewell editorial, “The Censorship of Vanguardia.” According to the editorial, the final blow was approval of the communications law, which creates a state watchdog entity to regulate media content and is filled with ambiguous language demanding that journalists provide accurate and balanced information or face civil or criminal penalties.

One provision, which prohibits supposed “media lynching,” would have been especially problematic for Vanguardia reporters. “Lynching” is defined as “the dissemination of concerted and reiterative information … with the purpose of undermining the prestige” of a person or legal entity. Of course, in-depth reporting often requires publishing a series of stories that would easily be construed as harassment by the government’s new media watchdog.

“We will never tolerate any of this,” said the editorial. “To continue publishing under these new conditions “would be undignified and contrary to the values that we defend.”

Calderón and his editorial staff disagree. They published a separate note to readers in the final online edition stating that the decision to close was premature and “not equal to the challenges” that the country and the media face under the new communications law. Calderón told CPJ that Vanguardia should have soldiered on because it remains unclear how and to what degree the new restrictions will be enforced. If the rationale that Vanguardia could no longer publish was really true, he added, then all Ecuadoran newspapers and newsmagazines would have to shut down.

Vanguardia operated on a tight budget, Calderón said, leading him to believe the shutdown may have been business related as well. But he pointed out that the magazine had been redesigned just a few weeks ago, so the closing took the editorial staff by surprise. Although all the stories for the final edition were ready, Calderón added, the order to print was suddenly cancelled, the magazine’s Internet servers were temporarily blocked, and the locks on the office doors were switched–although it was unclear by whom. Calderon told CPJ that the magazine’s print circulation was about 7,000 copies and that it had about 40,000 readers of the online version.

Francisco Vivanco, an Ecuadoran lawyer who owned Vanguardia and who is also president and a principal owner of the Quito daily La Hora, did not respond to phone calls or emails from CPJ last week seeking further comment about the closing. Vivanco is now involved in a legal dispute with out-of-work Vanguardia journalists over severance pay.

“This isn’t the way to fight the communications law–by sinking the boat,” Calderón said. “The thing to do is to give the good fight, to publish despite the new conditions.”