The writer spent months trying to find a colleague secretly jailed in the Gambia. Then he took the witness stand.

The shock of “Chief” Ebrima Manneh’s arrest set in gradually.

We were in our Banjul newsroom on July 7, 2006, working on the next issue of the Daily Observer, when two plainclothes officers with the Gambian National Intelligence Agency (NIA) approached Chief. I knew one of the officers as a Corporal Sey. They told Chief, a subeditor and reporter at the paper, that he was needed at the Bakau police station for questioning. He went along voluntarily, leaving his bag behind and saying he was confident he would be back soon. As the hours passed, we called his cell phone, to no avail. Worry set in, and we informed his family.

Chief has been spotted only a handful of times since—and not at all in many months—while the government has officially denied knowledge of his detention. My own reporting on his disappearance took me across much of the country over a period of months. I was able to confirm his location at various times through my sources, but the police shuffled him from place to place, a step ahead of me and the others concerned about his fate.

Though he was never charged with a crime, Chief’s arrest stemmed from his decision to republish a BBC story critical of President Yahya Jammeh’s democratic credentials on the eve of an African Union summit in Banjul. Editors at our pro-government paper overruled Chief’s decision, pulling the printed copies that carried the story and withholding them from distribution.

I worked with Chief for almost eight years, and he had become a good friend. Chief, whose nickname was that of the traditional ruler, started as a freelancer at the Observer and rose through the ranks, along the way introducing a popular weekly column called “Crime Watch.” As his absence stretched from days into weeks, journalists throughout the country became concerned. The government maintained an official silence even as police hid Chief from view.

Throughout my reporting, it was difficult to get information. Many people were scared to talk, thinking that they might be the next victim. When I arrived at the offices of possible sources, they would tell me they were busy. “See us again, but don’t call or record us,” they would say. It occurred to me that I could be targeted, too, but I tried to push that to the back of my mind and remember that I had a job to do.

I learned from prison, police, and NIA sources that within the first four weeks of his confinement, Chief was moved from the Bakau station to NIA headquarters in Banjul, to the nearby Mile Two Central Prison, and then back to the NIA. By September, I had tracked him to a police station in south-central Sibanor, only to be told he had been transferred to Fatoto Prison in far western Gambia.

In mid-December 2006, reporter Yaya Dampha of the opposition daily Foroyaa saw Chief briefly in Fatoto Prison. After Foroyaa reported the sighting, I learned from an inmate there that Chief had been moved yet again, back to Mile Two, then on to a facility in western Sare Ngai. The press freedom group Media Foundation for West Africa quoted an eyewitness as having seen Chief in July 2007 at Banjul’s Royal Victoria Teaching Hospital, where he was being treated for high blood pressure.

But the trail grew fainter by the month. Chief’s father met with then-Director General Harry Sambou of the NIA and Ousman Sonko, secretary of state for the interior, and was told that the government was not holding his son.

By November 2007, I had become presidential correspondent for the Observer and was still pursuing the case when I got a call from a friend in Dakar, Senegal. Come here, he said vaguely, and bring all your personal documents. There was an important opportunity, he suggested. I was confused and put him off, saying that I couldn’t leave work so suddenly. He was persistent, though, and said he could arrange for me to get some time outside the Gambia. He enlisted a female friend to call my boss, Dida Halake, who was then the paper’s managing director. Pretending to be secretary to the Gambian High Commissioner in Dakar, the woman asked that I be allowed to cover a conference in Senegal. The ruse worked. Halake gave me the green light.

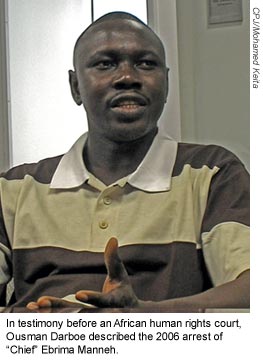

My friend greeted me when I arrived in Dakar on November 23. He wanted a favor: my testimony. The Media Foundation was presenting a case to the Community Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States. The group was asking the regional human rights court to declare Chief’s arrest illegal and to order his immediate release. They needed me to describe the circumstances of his arrest and my subsequent efforts to find him. Kwame Karikari, the Media Foundation’s chief executive, urged me to help. The case, he said, could be dismissed without my testimony.

I was reluctant. I thought of all of the repercussions—for me, my wife, and my two children. I said no. As the meeting went on and the Media Foundation pressed further, I recognized that, as Chief’s friend and colleague, I had an obligation to do anything I could to help set him free. I agreed to be a witness, and we made plans to travel to Abuja, Nigeria, where the court proceedings were being held.

I was reluctant. I thought of all of the repercussions—for me, my wife, and my two children. I said no. As the meeting went on and the Media Foundation pressed further, I recognized that, as Chief’s friend and colleague, I had an obligation to do anything I could to help set him free. I agreed to be a witness, and we made plans to travel to Abuja, Nigeria, where the court proceedings were being held.

Everything in my life abruptly changed. I called my wife and asked her to come to Dakar with our children. For the next two months, they would stay with my colleague Amie Joof-Cole, a former Radio Gambia broadcaster working in Dakar, while our lives were being rearranged.

On November 26, 2007, I testified before a three-judge panel at the Community Court. For 45 minutes, I detailed Chief’s arrest and described what I had learned about his placement in various prisons and police stations. Yaya Dampha testified as well.

Some good news followed. My family and I reunited in January of this year, and we resettled in the United States (in a town I keep secret for security reasons). I am homesick and miss my aging father, but we are living happily. In June, the Community Court ordered the Gambian government to release Chief immediately and to pay his family damages of US$100,000. His arrest, the court determined, was unlawful.

But the Gambian government has ignored the court’s ruling, just as it ignored the inquiries of Chief’s family and friends. Some people suspect Chief may even be dead, given the lack of recent information about his whereabouts and health.

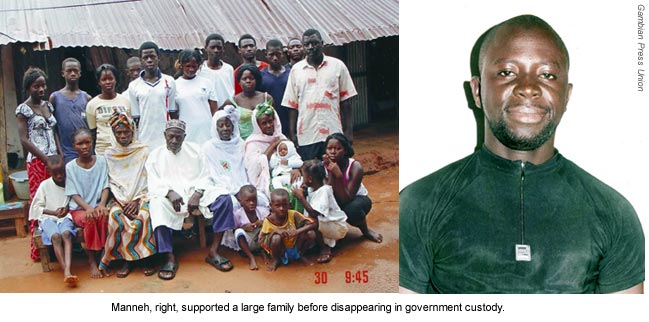

Chief’s disappearance continues to affect me deeply. He was the breadwinner in his family. At the time of his arrest, he was planning to be married and to finish construction of a new home. I would do whatever I could if my actions could reunite him with his family. I would testify again if my words could set him free.

Ousman Darboe was news editor and coordinator for the Observer Business Magazine, and later presidential correspondent for the paper.