To request a printed copy of this report, e-mail [email protected].

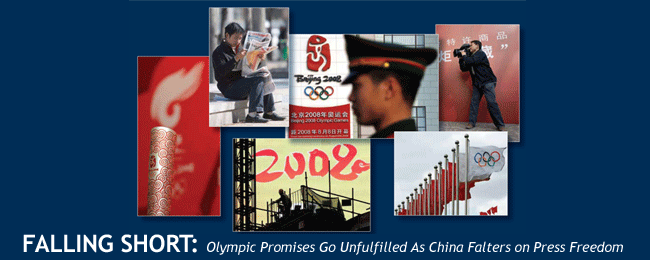

10. Opportunity Dissolves: Foreign Media Still Obstructed

Despite new rules that were supposed to allow greater freedom, officials continue to interfere with foreign media. Dozens of journalists are barred from covering the Tibetan unrest.

When the Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued liberalized reporting rules for foreign media in January 2007, it was an encouraging step. The temporary regulations, which are set to expire in October 2008, state that foreign journalists no longer need advance permission from provincial authorities for every interview they conduct, and that reporters are free to visit “places open to foreigners designated by the Chinese government.”

In practice, however, the government continues to interfere with foreign reporters. During the first 16 months under the new “Olympic regulations,” the Foreign Correspondents Club of China (FCCC) recorded more than 230 cases of obstruction or detention of foreign journalists and harassment of their sources. In some cases, journalists were able to resolve problems by contacting the Foreign Ministry in Beijing, but more often, local authorities simply ignored the new rules.

This was most evident after March demonstrations in the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, led to riots by ethnic Tibetans and protests in Gansu, Qinghai, and Sichuan provinces. More than 50 foreign journalists were turned away by police when they tried to enter areas where disturbances were reported, according to complaints compiled by the FCCC. Local officials invoked emergency powers to simply override the Olympic reporting regulations—a step that could not have been taken without the consent of the central government in Beijing.

FCCC records reflect a litany of obstruction: Police detained a Finnish Broadcasting Co. crew outside the monastery town of Xiahe, Gansu province. Authorities twice turned back a reporter for U.S.-based National Public Radio in Gansu—and then followed her car for more than 200 miles. Police blocked a crew from the American television network ABC from filming in a Tibetan neighborhood in Chengdu, Sichuan province. When the crew cited the Olympic rules allowing foreign reporters to travel and interview anyone who consents, an ABC reporter said, a police officer “simply shrugged and hailed us a taxi.”

Two weeks after the rioting erupted, authorities finally allowed a small number of handpicked foreign journalists into Lhasa—but access was limited to an official tour that was closely managed by government minders.

Foreign news coverage of the unrest, incomplete as it was, sparked a backlash in China. Official statements demonizing Western media and alleging bias in news coverage of the Tibetan crisis fostered a hostile environment, the FCCC said. At least 10 foreign correspondents reported receiving anonymous death threats, and numerous other journalists said they received harassing phone calls, e-mails, and text messages. The tensions prompted the FCCC to issue security tips to its members and to warn that “interference and hate campaigns targeting international media may poison the pre-Games atmosphere for foreign journalists.”

Bracing for the 21,500 accredited and 5,000 to 10,000 unaccredited foreign journalists who will descend on Beijing for the Games, China’s Olympic planners have issued police an English phrasebook.

It gives some indication of the welcome that foreign journalists will receive. In a section titled, “How to Stop Illegal News Coverage,” the practice dialogue features a police officer confronting a reporter who tries to cover a story on the outlawed religious group Falun Gong.

GUIDELINES FOR REPORTERS ON THE GROUND

Although authorities have tried to be more media-friendly for the Olympics, they are still determined to control information.

“Excuse me, sir. Stop, please,” says the officer politely but firmly, before explaining in impressively advanced English: “It’s beyond the limit of your coverage and illegal. As a foreign reporter in China you should obey China law and do nothing against your status.” “Oh, I see. May I go now?” says the visiting reporter hopefully. “No. Come with us,” the officer is told to reply at this point. “What for?” “To clear up this matter.”

Usually, detentions are more inconvenience than hardship for foreign journalists. The interrogators are generally polite and freedom usually comes after two to six hours of questioning. Unpleasant as it is to be taken away by police, there have been few long-term repercussions in recent years. No foreign journalist has been expelled from China in more than five years.

In late March, Jonathan Ansfield of Newsweek filed an account of his experiences trying to cover the ethnic Tibetan riots on his blog. His advice to colleagues if they are detained: “It cannot hurt us to put up a little fight. … Stipulate your ‘rights’ and any ‘violations’ thereof. Counter questions with questions or non-answers. Yes, apologetic kowtowing does speed the process, if you have no other leg to stand on. Otherwise, I say, try a few histrionics. Look tough. Make a wisecrack. Go a little batty. A modicum of brusqueness may discourage police from taking advantage of a detention-type situation. Not that anything is ever guaranteed. (Disclaimer: Such funny stuff is not recommended for Chinese passport-holders.)”

Ethnic Chinese and other Asian reporters, in fact, have been treated harshly. Ng Han Guan, an Associated Press photographer, was clubbed and his camera smashed by plainclothes security personnel when he took a picture of a colleague being manhandled by police after the Asian Cup final in Beijing in 2004. BBC producer Bessie Du and cameraman Al Go were strip-searched by police after they visited a riot scene in Dingzhou village, Hebei province, in 2005.

Chinese sources face particularly severe repercussions. It is as if there is a circle of fire around foreign correspondents in China—one that protects the reporters but threatens anyone they come near. Among the high-profile victims in recent years have been human rights activist Hu Jia, peasant rights advocate Chen Guangcheng, and legal rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng, all of whom are either in prison or re-education camps, or have been intermittently held in detention. All three men regularly spoke to the media, local and foreign, and knew the chances they were taking. Hu, a high-profile advocate and prolific writer, was sentenced to three and a half years in prison in April for, among other reasons, comments he made during two interviews with foreign media. Visiting journalists must realize the potential cost to Chinese citizens who agree to speak with them.

Journalists’ assistants are vulnerable as well. New York Times researcher Zhao Yan served three years in prison, ostensibly for fraud. But his supporters say the charge was a fig leaf to cover the real reason for his punishment—a 2004 Times story that correctly predicted former President Jiang Zemin was about to step down as head of the Central Military Commission.

Under the Olympic guidelines, foreign news outlets operating in Beijing, Qingdao, Shanghai, Tianjin, Shenyang, and Qinhuangdao are supposed to hire local assistants through authorized service organizations. Elsewhere, reporters should contact the provincial foreign affairs office. But with thousands of visiting reporters looking for temporary translators, fixers, and coordinators for the Games, many Olympic hires are bound to be unregistered. And many will be enthusiastic young people with little journalism experience.

Foreign news teams should be careful not to put them in jeopardy. Although several news organizations use Chinese assistants as contributing reporters, these assistants cannot legally be credited with exclusive bylines. Reporters who ask Chinese hires to arrange meetings with activists or to organize a visit to an AIDS village must realize that they could be putting their Chinese colleagues at risk. These assistants might not be punished until after the Games, when the world’s attention has moved on.

Reporters from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan have seen the government lift, at least for now, the requirement that they obtain prior permission from provincial authorities for reporting trips outside Beijing. Reporters based in Hong Kong say they are still expected to get special approval from the central government or the official Xinhua News Agency to cover stories on the mainland, but nobody has paid heed to this stipulation for years. Hong Kong journalists foresee few problems covering the Games but say difficulties may arise if they try to cover sensitive topics. The depth of that quandary was illustrated by the case of Ching Cheong, a Hong Kong resident and veteran correspondent with The Straits Times who served nearly three years in prison on spying charges that he adamantly denied. Ching was released in February.

Watching China prepare for the Games, it is clear the government wants the event to be flawless. That preoccupation has led to overly aggressive attempts to control the media. Past experience has shown that China tends to err on the side of heavy-handedness when it comes to media control and threats to the country’s image as a unified nation. Reporters traveling to China should be aware of the risks to people they interview or hire, as well as the dangers they face themselves.