By Ivan Karakashian

A Yemeni editor’s decision to reprint cartoons of Muhammad sparks government reprisals. Other cases abound.

| When Yemen Observer Editor Mohammed al-Asaadi gathered his editors February 1 for their regular meeting to pick the top story for the next edition, the choice seemed clear. Thousands of Palestinians were demonstrating in Gaza, a retail boycott of Danish goods was gaining momentum, and Saudi Arabia and Syria had just withdrawn their ambassadors to Denmark. The issue that sparked the discontent–a Danish newspaper’s publication of cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad–had become the talk of the world.

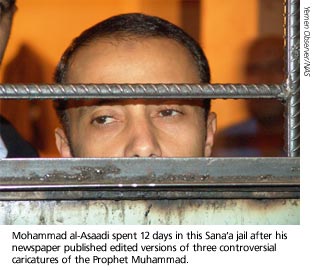

Sidebar:Worldwide, Arrests and Shutdowns The February 3 issue included a front-page news story, along with commentary and sidebars on three inside pages. The Observer‘s main editorial decried the drawings as an insult to Islam. The obscured cartoons ran on page 11, next to a photo of people boycotting Danish goods. The issue was distributed widely, and for three days there was no adverse reaction. Then al-Asaadi received a phone call informing him that the Ministry of Information had suspended his paper’s license to publish. “A friend of mine called from Rome and told me Reuters reported that our license was suspended,” al-Asaadi said in an interview with the Committee to Protect Journalists. “I had no idea because the Ministry of Information did not tell me the paper was closed.” But closed it was, he soon learned, as it remained for three months. The prosecutor for press and publications in Sana’a summoned al-Asaadi and Faris Abdullah Sanabani, the paper’s publisher and a media advisor to President Ali Abdullah Saleh, for questioning on February 11. Sanabani was relieved of responsibility, but al-Asaadi was detained for printing materials deemed offensive to the Prophet. The prosecutor told al-Asaadi’s lawyer that the journalist was being held for his own protection. Al-Asaadi spent the next 12 days in a poorly ventilated basement cell, along with a dozen or so other detainees. At night he found it difficult to breathe amid clouds of cigarette smoke. Having never spent a day in prison before, the experience shocked him; he kept a daily journal as a means of coping. The attorney general later charged al-Asaadi with insulting the Prophet under both the penal code and the press law and released him on bail. At least 14 private lawyers recruited by Sheik Abdul-Majid Zindani, chairman of Islah Shura Council, filed complaints against al-Asaadi and called, at least indirectly, for his execution. Yemeni law permits private individuals to take a criminal case to court if they believe their civil rights have been infringed. Al-Asaadi faces severe jail time and a possible death sentence for his editorial decision. The controversy began last September when the Danish daily Jyllands-Posten published 12 caricatures of Muhammad, one of them depicting the Prophet wearing a bomb-shaped turban with a lit fuse. The publication caused anger in the Muslim world, where many consider depictions of Muhammad to be blasphemous. The cartoons gained greater attention after they were reprinted in the January 10 edition of Magazinet, a small Christian evangelical weekly based in Norway, and then republished by publications across Europe and the World Wide Web. By February, protests, some of them violent, were reported in several cities. Throughout the Muslim world, a number of publications printed versions of one or more of the cartoons for various reasons: to denounce them, to mobilize protests against them, or to appeal against the violence they spurred. Many of the publications were targeted as a result, becoming easy prey for governments seeking a pretext to retaliate against the press, curry favor with Islamists, and deflect public attention from domestic problems. Worldwide, the Committee to Protect Journalists found that at least nine publications were closed or suspended and 10 journalists were criminally charged. Punitive actions, including censorship orders and harassment, were reported in 13 countries, CPJ found. In Syria, merely commenting on the cartoons drew government retaliation. Adel Mahfouz was charged by the Damascus prosecutor’s office after writing an article on the news Web site Rezgar advocating peaceful dialogue as a means of protesting the cartoons. Mahfouz was charged with insulting public religious sentiment under the penal code. If convicted, he faces up to three years imprisonment. The Syrian government was eager to exploit the debate for internal political gain, said Bernard Haykel, associate professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic studies at New York University. “It is a minority Alawite regime that needs to burnish its Islamic credentials and therefore would have used the occasion of the caricatures to do just that,” Haykel said. The case, he said, also distracted attention from major challenges facing Bashar al-Assad’s regime, notably its withdrawal from Lebanon and alleged links to the 2005 assassination of former Lebanese prime minister Rafiq al-Hariri. Yet nowhere was retaliation as severe as in Yemen, where the government sought to make censorship a popular cause. Muhammad Shaher Hussein, the deputy information minister, said his agency wanted to ease public tensions when it suspended the Observer and two other publications–the private weekly Al-Hurriya Ahliya, and the Arabic-language Al-Rai Al-Aam–for reprinting the cartoons. The suspensions appeared to contravene Yemen’s own press law, which states that only a court has jurisdiction to suspend or revoke a publication’s license. Prime Minister Abdelqader Bajammal finally lifted the bans on May 2. “They can get away with breaking their own law because they appear to be responding to public demand,” said Sheila Carapico, a professor of political science and international studies at the University of Richmond. The Danish caricatures are “something on which the public and government can pretty much agree,” Carapico said. “It’s a distant enemy, an amorphous enemy, it’s not something they can really do anything about–and so it has all the advantages of symbolic politics that are really policy neutral.” Yemeni authorities filed criminal charges against three other journalists: Abdulkarim Sabra, managing editor and publisher of Al-Hurriya; Yehiya al-Abed, a journalist for Al-Hurriya; and Kamal al-Aalafi, editor-in-chief of the Arabic-language Al-Rai Al-Aam. They were charged with violating Article 103 of the Press and Publications Law of 1990, which prohibits “printing, publishing, circulating, or broadcasting … anything which prejudices the Islamic faith and its lofty principles or belittles religions or humanitarian creeds.” They also face penal code charges. “The government sees us becoming more independent and increasingly writing about sensitive issues against the government’s interests,” al-Asaadi said. His newspaper, while often sympathetic to the president, has also reported on alleged corruption in the Yemeni foreign service. “The message to the Yemeni press,” al-Asaadi said, “is that the government can mimic these circumstances and carry out the same sort of measures when the press does something they don’t like.” But the press itself played into the hands of governments through sensational and superficial coverage, al- Asaadi and other journalists told CPJ. “We are responsible for what’s happening to us. We played a role,” said al-Asaadi, who cited his own case as an example. “During my initial arrest, the Yemeni press didn’t provide further information or try to clarify the context, reporting simply that I had published the cartoons.” During al-Asaadi’s first hearing in the General South-West Court in Sana’a on March 8, prosecution lawyers seemed to call for al-Asaadi’s execution by recounting a story in which Muhammad praised a companion for killing a woman who had insulted him. The prosecution team stated further demands in a second hearing on March 22. “When the Yemen Observer published the pictures they were aware of the anger caused by them,” according to a statement read in court by the prosecution. “We demand the punishment of its editor-in-chief, the permanent closure of the paper, and for Mohammed al-Asaadi to be banned from writing for newspapers forever.” The prosecution team also seeks financial compensation–for itself–because of the psychological trauma the Yemen Observer allegedly caused, according to the statement. Context is at the root of the case: The defense wants the cartoons to be judged as part of the Observer‘s full coverage, including the accompanying text and the placement of the drawings. The attorney general and prosecution team have argued that al-Asaadi should be judged on the published drawings alone. Beyond the legal battles, al-Asaadi fears for his life because of the nature of the charges. Lengthy intervals between court dates increase the risk, as accusations linger without resolution. Some members of Parliament chimed in to demand severe punishment, apparently believing that the Observer printed all of the drawings in their original form. “When we clarified to members of Parliament they withdrew their position and cooperated with us. Religious scholars sympathized with us after we explained our position,” al-Asaadi said. “But there was a campaign of provocation in the beginning, forcing one to worry about his life.” Likewise, al-Asaadi worries about the 35 employees at the Yemen Observer. “I actually feel depressed and kind of frustrated from the situation,” al-Asaadi told CPJ. “The suspension of the paper, no work, fears of any silly behavior from fanatics, the uncertain end of the ordeal–it has had a negative impact on my family.” Sanabani, the publisher, said the Observer maintained an Internet presence throughout the suspension, but it lost considerable money during the three months that the print version was banned. The Observer, a nine-year-old publication, sold 8,000 copies before the suspension, primarily to foreign diplomats, business people, and officials with non-governmental organizations. Al-Asaadi believes the judge will not order his execution or even imprisonment once attorneys present his defense. Still, the ordeal has left him broken. “I chose this profession out of passion and belief to contribute in bringing about a change for the best of this society,” al-Asaadi said. “After years of dedication, I am facing death threats in all corners of the streets for nothing but practicing my job and calling for understanding. I have to explain to every individual that I am innocent.” |

|

|

Here is a rundown of reprisals worldwide in the cartoon controversy. Except where noted, the actions came in response to publishing versions of one or more of the cartoons. • Countries where reprisals were reported: 13 Algeria: Two editors criminally charged. |

|

| Ivan Karakashian is research associate for CPJ’s North Africa and Middle East program. |

The English-language weekly decided to reprint three of the drawings, in black and white and reduced size, with large X’s overlaid on each, as part of multiple-page coverage of the controversy. The editors wanted to denounce the cartoons, explain to the mainly foreign readership of the Yemen Observer why they elicited outrage among Muslims, and to show readers exactly what was under protest. The decision to reprint a small selection was unanimous among the editors, some of whom objected only to obscuring the drawings with X’s. Al-Asaadi, described by colleagues as a devout Muslim, insisted on the markings to make clear the paper’s view that they were inappropriate.

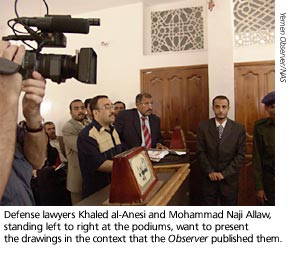

The English-language weekly decided to reprint three of the drawings, in black and white and reduced size, with large X’s overlaid on each, as part of multiple-page coverage of the controversy. The editors wanted to denounce the cartoons, explain to the mainly foreign readership of the Yemen Observer why they elicited outrage among Muslims, and to show readers exactly what was under protest. The decision to reprint a small selection was unanimous among the editors, some of whom objected only to obscuring the drawings with X’s. Al-Asaadi, described by colleagues as a devout Muslim, insisted on the markings to make clear the paper’s view that they were inappropriate. Mohammed Naji Allaw, a lawyer with the National Organization for Defending Rights and Freedoms, is helping defend al-Asaadi. “The intention of the Yemen Observer was to criticize the Danish press,” Allaw told CPJ. “He did not intend to insult the prophet; he did not intend to republish the cartoons in their support. … Al-Asaadi was defending the prophet, and he should be found innocent.”

Mohammed Naji Allaw, a lawyer with the National Organization for Defending Rights and Freedoms, is helping defend al-Asaadi. “The intention of the Yemen Observer was to criticize the Danish press,” Allaw told CPJ. “He did not intend to insult the prophet; he did not intend to republish the cartoons in their support. … Al-Asaadi was defending the prophet, and he should be found innocent.”