Under Haiti’s new transitional government, journalists-especially those who supported former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide-remain at risk in a politically polarized environment.

By Carlos Lauria and Jean-Roland Chery

Nearly five months after the ouster of President Jean Bertrand Aristide, journalists in Haiti still confront great dangers in a country marked by lawlessness. Before the unrest began in September 2003, journalists working for private radio stations were often targeted for their anti-Aristide coverage. But the nature of the threat has shifted, with journalists who supported Aristide now at particular risk, an investigation by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has found.

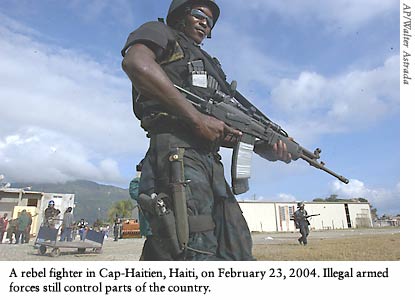

CPJ interviews and research also show the problem is acute in Haiti’s rural northern and central regions, where former rebels have threatened, harassed, and illegally detained journalists. These former rebels–illegal armed groups and former members of the disbanded Haitian military–have become de facto security forces in rural regions where police presence is minimal. Fearing for their safety, a number of journalists in Haiti’s northern and central regions have gone into hiding, according to the Haitian Journalists Association (AJH).

In the last four months, CPJ has documented three cases in which former rebels have illegally detained journalists working for pro-Aristide radio stations. At least one broadcaster has closed its doors, and another suspended news reports for a month while under threat.

The new provisional government has pledged to disarm the former rebels, although it, too, has been accused of taking legal and regulatory steps to stifle pro-Aristide media.

The threats are, in part, a legacy of Haiti’s polarized media environment–one in which news outlets themselves became closely tied to political positions at either extreme. While the targets of attacks may have changed, analysts say, Haitian journalists will never be able to pursue their work freely until all of them can work without the threat of violence.

The New Targets

The New Targets

Georges Venel Remarais, director general of both Radio Solidarité and the news agency Agence Haïtienne de Presse, says that following Aristide’s departure, his radio station did not broadcast news for a month after receiving threats.

“Journalists working for this station have serious problems, especially in the countryside. We are being persecuted, and we feel in danger,” says Remarais. The problem is exacerbated, he notes, because much of the private media are sympathetic to the new transitional government. “The arrests of journalists perceived as pro-Aristide are not reported by the private media. They don’t say a word about it,” he says.

On March 30, Lyonel Lazarre, a correspondent for Radio Solidarité and Agence Haïtienne de Presse in the southern city of Jacmel, was abducted and beaten by a group of former rebels after he reported alleged abuses by police forces in the neighboring town of Belle-Anse. Lazarre was released the next day.

Charles Prosper, a correspondent for Radio Tropic FM in the central city of Mirebalais, was abducted on May 15 by a group of former rebels and detained for two days. The group kidnapped Prosper for broadcasting reports about the volatile political situation and accused him of having ties to Aristide’s Fanmi Lavalas party.

The new government has also taken steps to suppress pro-Lavalas media. On May 18, transitional authorities closed the offices of Radio-Télé Ti Moun, which is owned by the Aristide Foundation for Democracy, an organization that Aristide founded in 1996. Ten days later, police arrested Télé Ti Moun cameraman Aryns Laguerre in the capital, Port-au-Prince.

The new government has also taken steps to suppress pro-Lavalas media. On May 18, transitional authorities closed the offices of Radio-Télé Ti Moun, which is owned by the Aristide Foundation for Democracy, an organization that Aristide founded in 1996. Ten days later, police arrested Télé Ti Moun cameraman Aryns Laguerre in the capital, Port-au-Prince.

Mario Joseph, a prominent Haitian lawyer who defended both Laguerre and Radio-Télé Ti Moun, says the journalist’s arrest and the outlet’s closure were politically motivated.

Minister of Justice Bernard Gousse says that Radio-Télé Ti Moun was closed for financial irregularities that are now being investigated. Station technical director Jean Marie Plantin says no evidence has been presented yet.

“The arrest and the shutdown are illegal. The order to close the stations came from the education minister, Pierre Buteau, who has nothing to do with this issue,” Joseph argues. In the case of Laguerre, Joseph says that he was arrested at his home and detained “only for his job as a Télé Ti Moun cameraman.”

A Polarized Press

Long before Aristide was forced out, the Haitian press was sharply divided. During the 29-year dictatorship of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and his son Jean-Claude “Baby Doc,” which ended in 1986, any attempt to create an independent press was brutally stifled. Even after the fall of the Duvalier regime, it remained difficult for journalists to organize themselves and work freely because an unstable series of short-term rulers prevented the press from getting on its feet.

In 1994, with the return of ousted Aristide, Haitian journalists like Jean Dominique dusted off their microphones. But Aristide’s return sharply divided Haitian society, including the press. The Lavalas government accused the private media of working for the political opposition, while Aristide said the media had ties to wealthy patrons of former dictatorial regimes. Analysts say that the flawed May 2000 legislative elections, which Aristide’s Lavalas party swept, were seminal in further politicizing the private media.

The National Association of Haitian Media, a group of local media owners, actively participated in the Group of 184, an alliance of civil society organizations and political parties that organized demonstrations against Aristide and the Lavalas party beginning in 2003.

Many private radio stations openly promoted the opposition’s agenda, sometimes exaggerating or inventing stories. In early February, rebel leader Guy Philippe accused Aristide of sacrificing children in a voodoo ceremony–a fabrication presented as fact on some private radio stations.

Pro-government media outlets were not objective, either. The weekly Haiti Progrès described Haitians as “joyously” celebrating the nation’s bicentennial on January 1, 2004, virtually ignoring the violent clashes between protesters and police that dominated international news reports.

On February 29, Aristide fled Haiti after appeals from the United States and France to resign for the sake of his nation. The next day, Aristide claimed that he had been driven from power by the United States in a “coup,” an allegation dismissed by the White House as “complete nonsense.” Aristide first fled to the Central African Republican and is now living in asylum in South Africa.

On February 29, Aristide fled Haiti after appeals from the United States and France to resign for the sake of his nation. The next day, Aristide claimed that he had been driven from power by the United States in a “coup,” an allegation dismissed by the White House as “complete nonsense.” Aristide first fled to the Central African Republican and is now living in asylum in South Africa.

In February, as anti-Aristide rebels moved closer to Port-au-Prince, attacks against journalists intensified. On February 22, after effectively taking control of Haiti’s northern region, a group of armed rebels ransacked and torched the offices of the pro-Aristide radio stations Radio Afrika and Radio-Télé Kombit in the city of Cap-Haïtien. Sources told CPJ that both stations, which are owned by members of the Lavalas party, had been calling for violence against the armed groups before the rebels took over their airwaves.

The international press also became a victim of this vicious environment. As tensions increased, more than 200 foreign journalists arrived in Haiti to cover the events. On February 20, three Mexican journalists were attacked with machetes, stoned, and chased by a group of angry government supporters while covering a student demonstration in Port-au-Prince. Many Aristide activists were angered because they saw the international media as foreigners sympathetic to the rebel cause.

“It was a very intimidating atmosphere,” recalls Alberto Armendáriz, New York-based correspondent for the dailies Reforma (Mexico) and La Nación (Argentina) who spent more than a month covering the crisis. “Government supporters burned tires, blocked the roads, and set up checkpoints. They were heavily armed, attacked vehicles identified as press, and harassed foreign reporters covering opposition protests.”

In Port-au-Prince, Armendáriz shared a hotel room with friend Ricardo Ortega, a correspondent for the Spanish television station Antena 3. On March 7, Ortega was fatally shot when gunmen opened fire on demonstrators who were calling for the prosecution of ousted President Aristide and celebrating his departure.

In the same incident, Michael Laughlin, a photographer with the Florida-based daily Sun Sentinel, was shot in the face, neck, and shoulder. Laughlin, as well as several photographers caught in the crossfire, believe that pro-Aristide militants may have targeted journalists. Witnesses said Aristide supporters started the shooting, which killed seven people and wounded dozens, The Associated Press reported.

In the same incident, Michael Laughlin, a photographer with the Florida-based daily Sun Sentinel, was shot in the face, neck, and shoulder. Laughlin, as well as several photographers caught in the crossfire, believe that pro-Aristide militants may have targeted journalists. Witnesses said Aristide supporters started the shooting, which killed seven people and wounded dozens, The Associated Press reported.

Aristide supporter Yvon Antoine and police inspector Jean-Michel Gaspard were arrested in late March and are being investigated for their involvement in the incident.

Better for Some

Provisional Prime Minister Gerard Latortue’s 13-member Cabinet was sworn in on March 17. A former U.N. official, Latortue returned from Florida, where he worked as a business consultant, with promises to improve Haiti.

“Journalists are now free to search, gather, and disseminate information without government interference or fear of reprisal,” says Raymond Lafontant Jr., Latortue’s chief of staff.

And for Port-au-Prince-based private radio stations, which endured years of threats and attacks by Aristide supporters, the climate has certainly improved.

“Journalists in the capital are not threatened and attacked any more; we are working in a safer environment,” says Rotchild François Jr., news director of the private Radio Métropole.

But François points to the dangers outside Port-au-Prince. “There are still problems in northern and central Haiti, where former military are harassing and threatening provincial reporters,” he says.

The prime minister’s chief of staff, Lafontant Jr., acknowledges that illegal armed forces who fought for Aristide’s ouster still control sections of the country but says the government has given the groups a September 15 deadline to dispose their arms or have them seized. The government recognizes the importance of ending the cycle of impunity, he notes.

“For that reason we consider crucial that the investigations into the murders of two prominent journalists in recent years–Jean Dominique and Brignol Lindor–show prompt signs of progress,” Lafontant says. Dominique was killed in April 2000 and Lindor in December 2001; the killers have yet to be brought to justice. On July 1, a ruling by a court of appeals in the Dominique case allowed the stalled proceedings to resume after being blocked in court for almost a year. This ruling finally opens the door for the nomination of a new examining judge, who will conduct another investigation.

An Opportunity Lost

Meanwhile, journalists remain politically divided. The Haitian Journalists Association’s (AJH) June 7 award ceremony seemed to offer a rare opportunity for the country’s press to overcome those divisions. Journalists from across the political spectrum attended the Port-au-Prince event, one of the few times in recent memory that a media gathering drew such a diverse crowd. The awards themselves seemed to honor the same range of viewpoints.

One award went to Radio Hispagnola owner Pierre Elisem, who was shot and badly injured in a February attack by Aristide supporters. Another award, named in honor of Lindor, went to Radio Solidarité correspondent Jeanty André Omilert, who was abducted in April and held for several days by anti-Aristide forces.

One award went to Radio Hispagnola owner Pierre Elisem, who was shot and badly injured in a February attack by Aristide supporters. Another award, named in honor of Lindor, went to Radio Solidarité correspondent Jeanty André Omilert, who was abducted in April and held for several days by anti-Aristide forces.

But what could have been a rare show of unity among Haiti’s fractured press instead revealed the angry divisions that remain.

Critics howled that Omilert had been a lackey of the Aristide government, undeserving of an award named for Lindor. A member of the jury that chose Omilert said he was threatened. And amid the rancor, Omilert eventually rejected the prize.

The divisions themselves pose a danger to journalists, one press leader says.

“Journalists working in a polarized environment become blind,” argues AJH Secretary-General Guyler Delva, who says he is the juror who received three anonymous death threats after the awards ceremony.

“Reporters on both sides think that some colleagues should not have a voice or an opportunity to speak out because of their political background,” Delva says. “This division has created additional risks for Haitian journalists and will be very difficult to overcome in the near future.”

Carlos Lauría is CPJ’s Americas program coordinator. Jean-Roland Chery was a reporter with Radio Haiti-Inter and now lives in New York.