When will the United States stop compelling reporters’ testimony?

Commentary by Frank Smyth

WASHINGTON, D.C.

What kind of country forces journalists to name their sources, and what signal does it send worldwide? By most accounts, U.S. prosecutors have targeted more journalists this year than in decades, with federal judges ordering them to reveal confidential sources or face fines and jail. The Justice Department denies mounting a coordinated campaign. But there is no denying that authorities are demanding that journalists break one of the bonds that maintains a free, independent press.

For years, federal prosecutors and judges avoided calling journalists to testify in court, pursuing criminal and civil investigations by other means. But in Boston last March, a federal judge issued a contempt ruling against a correspondent for NBC’s Providence affiliate who refused to say who passed him an FBI surveillance tape during a corruption probe. The judge levied a $1,000 daily fine.

For years, federal prosecutors and judges avoided calling journalists to testify in court, pursuing criminal and civil investigations by other means. But in Boston last March, a federal judge issued a contempt ruling against a correspondent for NBC’s Providence affiliate who refused to say who passed him an FBI surveillance tape during a corruption probe. The judge levied a $1,000 daily fine.

Later this year, five reporters were held in contempt for refusing to comply with subpoenas in a civil lawsuit filed by former U.S. nuclear scientist Wen Ho Lee, who alleges Privacy Act violations in his case against the government. His lawyers wanted to determine which officials leaked confidential personnel files to the press, and a federal judge fined the reporters.

But the big blow came this summer, when Time correspondent Matthew Cooper was held in contempt and at least four other reporters were subpoenaed in a federal investigation into which administration officials leaked the name of a CIA operative. A government official’s willful disclosure of an undercover CIA officer is a crime.

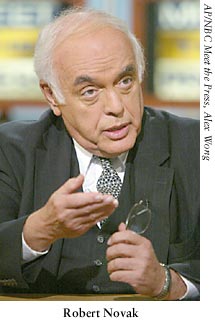

Here is where politics loom large–and the government’s strategy raises questions. Chicago U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald, a rising star in the Justice Department who was named special prosecutor to the case, put the initial squeeze not on syndicated columnist Robert Novak, who broke the story, but on several reporters peripherally involved, including two who never even wrote about it.

Here is where politics loom large–and the government’s strategy raises questions. Chicago U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald, a rising star in the Justice Department who was named special prosecutor to the case, put the initial squeeze not on syndicated columnist Robert Novak, who broke the story, but on several reporters peripherally involved, including two who never even wrote about it.

Novak named Valerie Plame as the CIA operative on July 14, 2003. Plame is married to former U.S. diplomat Joseph C. Wilson IV, whom the Bush administration sent to Niger to investigate allegations that Iraq was attempting to buy enriched uranium.

Novak’s column, which cited two unnamed administration sources, appeared eight days after Wilson wrote an op-ed in The New York Times challenging the government on the uranium issue. Other reports surfaced later with Plame’s identity, most suggesting that administration officials had leaked the name in retaliation against Wilson.

Justice Department spokesman Mark Corallo notes that Attorney General John Ashcroft typically  approves press subpoenas but says, “Pat is acting in his own capacity” as special prosecutor in the CIA case. Fitzgerald’s office won’t discuss his strategy, but he’s used aggressive tactics in other cases, with Ashcroft’s approval.

approves press subpoenas but says, “Pat is acting in his own capacity” as special prosecutor in the CIA case. Fitzgerald’s office won’t discuss his strategy, but he’s used aggressive tactics in other cases, with Ashcroft’s approval.

This summer, Fitzgerald obtained a subpoena for the telephone records of two New York Times reporters to learn whether government officials had leaked suspicions about an Islamic charity in Illinois. Times journalists queried the charity before a government raid, and prosecutors suspect charity officials of destroying documents before the FBI arrived.

In San Francisco, U.S. prosecutors sent letters to journalists from The San Francisco Chronicle and The San Jose Mercury News asking them to turn over documents and confidential sources for stories about alleged steroid use by professional athletes– including the source of grand jury transcripts, excerpts of which were published in the Chronicle.

Justice Department guidelines state that “the department’s policy is to protect freedom of the press, the news-gathering function, and news media sources.” Only in “exigent circumstances, such as where immediate action is required to avoid the loss of life, or the compromise of a security interest” may a journalist be compelled to testify. Even then it should come only after “the express approval of the attorney general.”

“We still follow our procedures on every case that comes through,” Corallo says. But thousands have signed a petition by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press in protest. Taken together, the cases send a message that the government is more willing to compel disclosure of confidential sources. Particularly troubling is the Plame case, where several journalists targeted were not involved in the story that gave rise to the potential crime.

“We still follow our procedures on every case that comes through,” Corallo says. But thousands have signed a petition by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press in protest. Taken together, the cases send a message that the government is more willing to compel disclosure of confidential sources. Particularly troubling is the Plame case, where several journalists targeted were not involved in the story that gave rise to the potential crime.

The world is taking notice. Many governments routinely compel journalists to cooperate with investigations, compromising their independence and obstructing their ability to gather news that officials want kept secret.

Press advocates won a significant international victory in The Hague in 2002, when a war crimes tribunal ruled that journalists should be compelled to testify only when “the evidence sought is of direct and important value in determining a core issue in the case … and cannot reasonably be obtained elsewhere.”

The U.S. government used to abide by an even higher standard. Today, it’s not clear where it will stop in compelling reporters’ testimony.

Frank Smyth is CPJ’s Washington, D.C., representative.