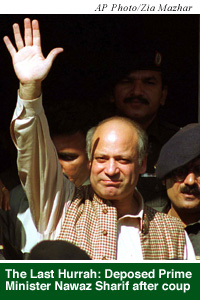

When Pakistan’s Gen. Pervez Musharraf unseated Prime Minister Muhammad Nawaz Sharif in a military coup on October 12, 1999, the common sentiment in Pakistan was that it was no great blow to democracy. Pakistani journalists, many of whom had been jailed, threatened and systematically harassed under Sharif, certainly shed no tears when Sharif was deposed. Of course, Musharraf’s unconstitutional assumption of absolute power was completely antidemocratic, but because he was replacing a leader who had himself taken to ruling like a despot, few seemed to mind about the technicalities.

In his two and a half years in power, Sharif had made a reputation for himself as a bully–not least because of the heavy-handed way he dealt with journalists who dared to criticize his government. Sharif was not unique in exploiting official power to silence his detractors. Pakistan has suffered a host of thin-skinned rulers, virtually all of whom, whether democratically elected or self-appointed, have used the available state machinery to try to control the press. But the Sharif administration did so with particular zeal and efficiency. His government ratcheted up the pressure on independent journalists, coupling more oblique strategies of muzzling the press with increasingly aggressive, public shows of retribution.

In February 1997, Sharif led his Pakistan Muslim League party to a landslide electoral victory, claiming his two-thirds majority in the National Assembly gave him a “heavy mandate” to rule the country as he saw fit. A protégé of Pakistan’s last military ruler, Gen. Zia ul-Haq, Sharif then proceeded to cast aside virtually every democratic check on his power. Among his challengers, he engineered the dismissal of a chief justice, forced a president to resign, and compelled an army chief to step down. He packed the courts and bureaucracy with loyalists, and rammed through constitutional changes eliminating the president’s authority to dismiss the prime minister.

As each democratic institution in turn was brought under Sharif’s personal control, the press became one of the few remaining checks on his power. “With the judiciary, bureaucracy, opposition, and parliament cowed by Prime Minister Sharif’s growing power, Pakistan’s lively and assertive press has become the only platform for substantive criticism of government policies,” wrote the Far Eastern Economic Review‘s Islamabad bureau chief, Ahmed Rashid, in a January 14 article for the Hong Kong-based weekly. “But even this avenue of expression may soon be blocked. The government is mounting what appears to be a concerted campaign to curb the country’s independent press.”

But in the end, the independent press survived while Sharif did not. In fact, it was the hammering that Sharif took in the press–which widely reported his administration’s alleged corruption, mismanagement, and abuses of power–that softened up public opinion for General Musharraf’s coup. While many Pakistani journalists were delighted to see Sharif go, they remain wary of the country’s new leader, because they realize that they continue to operate in an institutional vacuum.

The struggle of the press in Pakistan is a parable of the dangers that journalists face when the press is strong while other democratic institutions are weak. Pakistan is not the only example of this phenomenon. In Peru, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and Indonesia, for example, the press has also outpaced the development of the judiciary, the legislature, and even political parties. The reason is that unlike other pillars of democratic government, the press can develop independently, without government support or an institutional bureaucracy. And because it is decentralized, the press is often extremely difficult to control.

But journalists who work in such an environment are vulnerable to state repression. In a more fully developed democracy, journalists who expose government corruption can count on other institutions to step in and take up the cause. An independent attorney general could open an investigation; a congressional committee could hold hearings; political parties could use the allegations to force a leader from power. But in Pakistan, with no institution strong enough to challenge the administration, the press could count on little protection from Sharif’s wrath.

| Still standing

The press in Pakistan, despite more than four decades of government efforts to control it, is remarkably vigorous and aggressive. Though the airwaves remain a state monopoly, print media are, by comparison, virtually unregulated. (Go to footnote 1.) According to the Karachi-based Pakistan Press Foundation (PPF), 542 daily newspapers were published in Pakistan as of 1997. Though these papers vary widely in quality, the sheer volume and diversity of the country’s print media are impressive. “We have a very vibrant press here–no thanks to the government,” said PPF’s founder Owais Aslam Ali, during an interview in September, only a few weeks before Sharif was deposed. “It is not a compliant press. It is not a ‘press as an arm of development.’ It is the press as troublemaker. The role of watchdog is taken quite seriously.” The strength of the press is particularly remarkable in a country that has spent more than half its life under military dictatorships. Most recently, General Zia–who ruled Pakistan from 1977 until 1988–brutally suppressed media, imposing strict censorship controls and jailing journalists who tried to assert their independence. Many of the country’s senior journalists made great professional sacrifices during the Zia years, and guard their freedom all the more fiercely because of this history. The press’s centrality to public life has been critical considering the corruption and intermittent collapse of other institutions of civil society. Given a weak parliament, an often politically compromised judiciary, and a ramshackle higher education system, “the Pakistani press has been the forum where actual debate on issues of national importance has taken place,” noted Nasim Zehra, senior correspondent for the Islamabad edition of the national English-language daily The News. “It has in fact replaced what think tanks and political parties in other countries would do. Columnists engage in major debates and discussions on issues ranging from national security to the social sector.” |

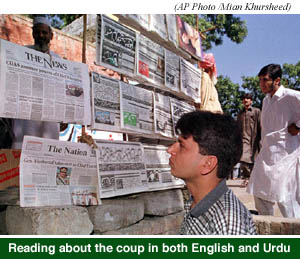

| Urdu versus English

The Pakistani press is not a monolithic body. Newspapers that publish in Urdu, the national language of Pakistan, have a far broader reach than the English-language papers, and they are typically subjected to greater pressures by the state. According to London’s Financial Times, the combined circulation of Pakistan’s entire English-language press is no more than 150,000 in a population of 134 million. Not surprisingly, Sharif initially focused his energies on controlling the Urdu-language press, while pointing to the relatively unfettered English-language press as evidence that the Pakistani media was operating freely. Whereas “in the English press, you have lots of freedom, comparatively, in Urdu, we have less,” noted Anwer Sen Roy, editor of the Urdu-language daily Kainaat, published in Karachi. “The Urdu papers are basically grassroots papers–with big circulation, and big impact . . . Even a single-column story creates some reaction.” One reporter whose stories appeared in both the English-language Fontier Post and its sister paper, the Urdu-language Maidan, both of which are published in Peshawar, said stories that had been ignored by government agencies when they ran in The Frontier Post created substantial controversy when they appeared in Maidan. “When English papers write, the government doesn’t bother, but whenever things are published in the Urdu-language press, they take serious note of this,” said the reporter. “When Maidan started publishing stories, the chief editor received threats that he may be killed or arrested by certain agencies.” (Go to footnote 2.) Afrasiab Khattak–chair of the Lahore-based Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, one of the country’s largest, most respected non-governmental organizations–told CPJ that Sharif generally gave the English-language press greater leeway for two reasons: “One, because the readership of the English press is very limited. Only the better-educated follow the English press, so the government doesn’t bother,” he said. “And, two, by allowing the English press to publish everything, the government gives the impression of freedom of the press to the world at large–particularly to the embassies in Islamabad. It’s sort of a window-dressing.” Despite the pressures, “there is more pluralism in the Urdu press than in the English press,” noted Ali of the Press Foundation. The English press is generally considered to be skewed toward a liberal, secular elite, while the Urdu press addresses the masses–and includes scandal sheets as well as serious journals, religious papers as well as party organs. In the southern province of Sindh, there is also a flourishing Sindhi-language press, which, like the Urdu press, varies tremendously in both content and quality–with politically progressive papers existing alongside publications that thrive on blackmail and extortion. |

| Press control: a primer

It is precisely because political leaders recognize the power of the press that they have spent so much energy trying to control it. Sharif distinguished himself among Pakistan’s democratically elected premiers only by the scale of his campaign against the independent press, not by its character. The primary institutional form of control is the “press advice system,” in which government officials constantly tell Pakistani newspaper publishers and editors how to behave and what to publish. The system was refined in the late 1970s, under General Zia. While it was supposed to disappear with Pakistan’s return to democracy in 1988, its basic mechanisms seem to have been preserved and were perpetuated by federal and provincial information ministries a decade later. The Sharif government used the press advice system extensively. Veteran journalist Zamir Niazi has spent a lifetime documenting attacks against the press in Pakistan. In his book The Web of Censorship, the mechanics of Zia’s system are outlined by A.S. Ghanvi, Director of Information under Zia. Press advice was handed down by the principal information officer in Islamabad, and processed by the staff of the press information department, whose job it was to “ensure that nothing against the directives crept into the press,” said Ghanvi. Information department staff sent written notices to the newspapers alerting them to the directives, and telephoned editors when necessary. “Sometimes we were asked to see that a certain story got full coverage or was played down and on which page,” said Ghanvi. That is quite similar to one senior editor’s account, from September 1999, of receiving daily calls from various Sharif administration officials–many of them from the information ministry–requesting that certain items be emphasized and others muted or eliminated altogether. “If a government requests to black out an item, we cannot accept, because this is our death,” said the editor, who works for the Urdu-language daily Jang. “But we can compromise. If a news [item] has a value of five columns on the front page, we can make it double-column on the front. Or if the threat is very high, we can make it single-column on the back.” Perhaps more startling than this journalist’s admission of editorial compliance with the government’s requests is his attitude toward the press advice system. “To some extent, we don’t feel hurt by their requests, because they are our client also,” said the editor. “They give us business–they give us advertisements.” Almost all the journalists interviewed by CPJ mentioned the press advice system as one of the most insidious threats to the profession. Under Zia, the system was buttressed by strict censorship regulations specifying that whoever “contravenes any provision of this regulation shall be punished with rigorous imprisonment which may extend to ten years, and shall be liable to fine or stripes [lashes] not to exceed twenty-five.” Though the system maintained under the Sharif administration was informal and without such prescribed penalties to ensure compliance, it seemed to have some effect. One prominent editor privately confided to the Far Eastern Economic Review‘s Ahmed Rashid that she had a rule of thumb: she would do what she was told one night out of five. “Other editors are playing the game much more,” Rashid told CPJ in September. “They’ll do it four out of five nights . . . And the more this goes on, and the more the press agrees to go along with it, the government thinks this can happen every night. It’s appalling.” Journalists also believed that the budget for the information ministry was substantially increased under Sharif, in order to help the minister and his staff woo journalists–and even place friendly journalists on newspaper staffs. Sharif did not rely exclusively on the press advice system to stifle independent reporting. As criticism of his administration mounted, he turned to cruder means, using intelligence operatives to infiltrate newsrooms and press unions. In early 1999, a major and a colonel from one of the intelligence agencies openly approached the Karachi Union of Journalists to request membership, according to one local journalist involved with union activities. With so many spies doubling as reporters, and journalists moonlighting as government agents, “now the biggest problem is lack of trust in each other,” he said. A colleague in Lahore echoed this sentiment: “The newsrooms are full of informers. You can’t trust anyone,” he said. The sheer number of nearly identical accounts of intelligence infiltration and intimidation gives credence to these journalists’ claims. Imtiaz Alam, current affairs editor at The News, said that he could literally observe the mechanics of the government’s spying operation from his private office, which has a window looking out onto the newsroom. “It’s all very obvious–because they do it at such an extensive scale,” he said. Alam said that he regularly witnessed newspaper staffers retrieving computer print-outs of his stories and making copies to distribute. “These copies are sent to various places, and then different feedback starts. We start getting calls. It happens everywhere.” In the two years preceding the coup, investigative reporter Amir Mir, a special correspondent for The News‘ investigative unit and a frequent contributor to the respected English-language publications Newsline and The Friday Times, wrote numerous stories exposing corruption and mismanagement in the Sharif administration. He also wrote unflattering stories about Shahbaz Sharif, who served as chief minister of Punjab Province during his brother’s term as prime minister, (Go to footnote 3) and Sen. Saif-ur-Rehman, one of Nawaz Sharif ‘s closest political advisors. In November 1998, Mir started receiving a series of anonymous phone calls. He said the most common threat he received was the warning that if he didn’t “stop writing against the prime minister, his brother and Saif-ur-Rehman, we will break your legs.” Mir also said that he was being routinely followed by agents from the Intelligence Bureau (IB). Under the Sharif government, the head of the IB reported directly to the prime minister. Journalists told CPJ that Sharif regularly used the IB to collect information about those whom he felt posed a threat to his administration–including members of the press. The administration was especially hostile to detailed reporting about the economic meltdown that resulted from Sharif’s May 1998 decision to match nuclear tests in neighboring India. The United States, which had backed Pakistan heavily during the Cold War, imposed crippling economic sanctions. Meanwhile, a threatened freeze on aid from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund sent foreign investors fleeing. An Islamabad-based reporter who covers economic affairs told CPJ that he was being followed almost weekly by IB agents. They would often flag down his car when he was returning from an interview and ask to whom he had been speaking and what he had discovered. He also received several anonymous phone calls warning him not to write stories that might harm Pakistan’s international standing. On a few occasions, they called my editors, friends, and senior colleagues,” he said. “Basically the message was, ‘You should be careful.’ “ Journalists also reported enormous pressure to toe the line on India. Relations between Pakistan and India, which have fought three wars since gaining independence in 1947, are typically strained. Tensions worsened after the tit-for-tat nuclear tests in May 1998. They approached the breaking point in the summer of 1999, when India and Pakistan fought a brief, undeclared war over Kashmir, a Muslim-dominated territory that both countries claim. Journalists told CPJ that during the conflict in Kashmir, which was at its most intense in the six weeks between the end of May and mid-July, any critical coverage risked being tagged “anti-state.” It was only after the fighting had ended that most journalists felt free to air criticism of Sharif’s decision to withdraw Pakistan-backed forces from Kashmir in the face of overwhelming international pressure. Reporting on Afghanistan was also sensitive [See “No Man’s Land, below] as the Sharif government maintained its close links with the country’s ruling Taliban militia while quietly promising Washington that it would use these connections to secure the extradition of Osama bin Laden, whom the U.S. accuses of having organized the August 1998 bombing of its embassies in Tanzania and Kenya. Bin Laden has been living in Afghanistan as a guest of the Taliban, whose repressive government has been recognized by only three countries in the world, including Pakistan. Some journalists who have written about the costs of Pakistan’s foreign policy received letters from the army-dominated ISI, warning them that their articles may “be helping the enemy in her evil designs”–a reference to India–and urging them to exercise greater restraint in the future. |

| Cracking down: the Jang Group

While the intelligence agencies worked mainly to encourage self-censorship, the administration also pursued several high-profile campaigns to demonstrate the high cost of disobedience. In the summer of 1998, in the wake of the economic crisis, the Sharif administration began focusing its offensive against the Jang Group of Newspapers. The Jang Group is a powerful media company that publishes one magazine and six newspapers–including the Urdu-language daily Jang, with a circulation of about a million, and the English-language daily The News. By October 1998, the income tax department had served the group with tax notices totaling more than 720 million rupees (about US$13 million). The company’s bank accounts were frozen, and its newsprint shipments blocked. On December 14, when the Jang papers ran stories about a financial scandal involving the Sharif family’s Ittefaq group of companies, the Jang Group’s Rawalpindi office was raided by authorities from the Federal Investigations Agency. Several journalists complained that their phones had been tapped, and that they were being followed by intelligence agents. Over the course of the showdown, the government used the income tax division, the customs authority, the intelligence agencies, the police, and its leverage over the courts to bring the publishing house to heel. This multi-pronged assault was engineered by the Accountability Bureau, an agency ostensibly established by the Sharif administration to investigate political corruption across the board, but regularly used by the prime minister to target his political opponents. In July 1998, Sen. Saif-ur-Rehman, who headed the bureau, held the first of a series of private meetings with Jang’s publisher, Mir Shakil-ur-Rahman (no relation), in which he asked the publisher to fire or demote more than a dozen senior journalists, promote the administration’s political agenda, and stop publishing news of the various scandals dogging Sharif and his allies. Evidence of the senator’s demands surfaced in January 1999, when Shakil-ur-Rahman released tape recordings of their conversations. In one of the press releases issued by Shakil-ur-Rahman during the crisis, the senator is quoted as saying, “These are the prime minister’s words, not mine. I have been ordered by him to convey all this to you.” By early February 1999, the Jang Group was running skeleton editions of its flagship papers, Jang and The News. Each typically runs around two dozen pages, but both were down to just four pages. With cases pending before the Income Tax Appellate Court and the Supreme Court, Shakil-ur-Rahman opted for closed-door negotiations with members of the administration. On February 9, the Supreme Court hearing was adjourned, and a spokesman for the Jang Group announced that “all controversial matters would be resolved amicably.” Though many journalists were disappointed that the Jang Group did not fight on, they understood that the system was stacked in the government’s favor. In particular, the Supreme Court’s political independence was far from assured after a series of cases in which the bench’s political allegiance to the Sharif administration appeared to trump constitutional considerations. “It would have been possible for us to continue our fight if there had been some faith in our judiciary,” said one prominent editor from the Jang newspaper. Exactly what Shakil-ur-Rahman agreed to in those closed-door sessions was not known, but many journalists at the Jang papers told CPJ that self-censorship was rife in the newsroom. And while Shakil-ur-Rahman did not dismiss any of the journalists singled out by the Sharif administration, several reporters were told to “lie low” for a time, and others urged to pursue less controversial stories. CPJ obtained an internal memorandum signed by Shakil-ur-Rahman and circulated among the newspaper staff in May 1999:

One of the most talked-about changes at the Jang Group was that the distinguished Dr. Maleeha Lodhi–then editor of the Islamabad edition of The News, former ambassador to the U.S. under Benazir Bhutto [and current ambassador to Washington under General Musharraf]–was no longer publishing anything in the paper under her own byline. Though newspaper management denied that Lodhi had been “banned” from writing as a result of pressure from the administration, her colleagues said it was highly unusual for her articles to appear in competing publications such as Newsline and The Friday Times, but not in her own newspaper. The Jang confrontation made the value of preserving an “open marketplace of ideas” clear to opposition groups, which staged impressive demonstrations in support of press freedom at the height of the crisis. A Karachi demonstration led by former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto included members of her Pakistan People’s Party, as well as followers of the Islamist party Jamaat-i-Islami and those of the ethnic-based Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM). None of these strange bedfellows had ever demonstrated any particular tolerance of free speech themselves, but opposition parties are typically great friends of the press when they are out of power. The Jang battle highlighted for many the awesome powers in the hands of the state. “The government has all the means to pressurize the press here,” explained Idrees Bakhtiar, Karachi-based correspondent for the BBC. “They control the advertisements. They control the newsprint. If a newspaper doesn’t toe their line, they can shut them down.” Such methods were used commonly–at both the federal and provincial level–to reward some papers and punish others. Many newspapers were forced to close when deprived of the government ads that were their staple. But the Jang papers had seemed invincible. Though they also rely on government ads, their circulation is so large that many expected them to survive without state support, at least for a limited time. But with all the state’s machinery working together, the big company was no better off than its smaller, poorer cousins. |

| The Sethi case

With the powerful Jang Group now partially tamed, Sharif turned his sights on Najam Sethi, the editor of the influential English-language weekly The Friday Times. By targeting the paper, a political weekly with a domestic readership estimated at around 50,000, Sharif demonstrated not only his government’s intolerance of criticism from any quarter, but also an awareness of the English press’s role in shaping the perceptions of the international community. Ultimately, Sharif’s lack of interest in maintaining a facade of democratic “window dressing” for the benefit of foreign diplomats and international investors backfired. Instead of masking the problems besetting his administration, Sharif inadvertently drew international attention to his autocratic tendencies. It was one of the more serious miscalculations of his political career. Sethi was arrested at his home in Lahore on May 8, beaten and gagged by government agents, secretly transferred from Lahore to a detention center in Islamabad, and held incommunicado for more than a week. The government eventually revealed that Sethi was being held by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency on suspicions that he had conspired with Indian intelligence operatives and might be guilty of treason. Sethi’s arrest followed his work with a BBC documentary team that was investigating corruption charges against Prime Minister Sharif and his family, but was also connected to The Friday Times‘ history as an independent political weekly that was often scathingly critical of Sharif’s policies. Sethi is a well-connected member of the Pakistani elite–not the sort of person one would have thought vulnerable to being brutally abducted in the middle of the night. As in the Jang Group case, the government’s persecution of Sethi was a signal that it would not spare anyone. At the time of Sethi’s detention, one journalist warned CPJ that the government was “trying to force a purge in the media of all liberal elements . . . And there are only about a dozen of us who would have to stop writing to make the press totally tame.” The Friday Times does not carry government advertising, making it less susceptible than the dailies to this major source of leverage. But the Sharif administration proved it had countless other means to encourage editorial compliance. The week after Sethi’s arrest, government agents seized the entire print run, and scared local printing presses so badly that none were willing to reprint the issue, according to Jugnu Mohsin, Sethi’s wife and the publisher of The Friday Times. (Go to footnote 4.) While the government ultimately released Sethi without charge on June 2, he was subjected to ongoing harassment for several months. Immediately following Sethi’s release, more than two dozen cases of tax evasion were filed against him. Sethi was also placed on the government’s Exit Control List, preventing him from traveling abroad. And on July 15, a politician from Sharif’s ruling Muslim League party filed a petition with the chief election commissioner seeking to disqualify Sethi from voting or running for public office on the grounds that he did not “fulfill the requirements of a Muslim” and was opposed to the “ideology of Pakistan.” Although the government ultimately backed down in both of these high-profile cases, many journalists felt that substantial harm had already been done. Within the Jang company, there was an overwhelming sense that the newspapers could not afford to antagonize the government again. “There’s a hanging sword on our necks,” said Anjum Rashid, Jang‘s senior editor in Lahore, speaking of the numerous cases against the Jang Group that had never been formally withdrawn. “They can be made live at any time,” said Rashid. “So we are behaving.” |

| Sharif in extremis

Nawaz Sharif’s efforts to control the press were part of a desperate bid to hold on to power. Though his moves to strengthen the prime minister’s hand at the expense of all other branches of government had made him one of Pakistan’s most powerful leaders ever, his autocratic style also isolated him, both internationally and at home. In mid-July, when Sharif acceded to U.S. demands to withdraw Pakistan-backed forces from Kargil, on the Indian-held side of Kashmir, he was widely condemned at home as a puppet of Washington who had too easily given up Pakistan’s hard-won tactical victory. Many analysts mark this moment as the beginning of the end for Sharif, as his handling of the Kargil crisis not only alienated powerful sections of Pakistan’s military establishment, but also exposed inherent contradictions between Pakistan’s foreign and domestic policies. Pakistani journalists played a key role in hastening Sharif’s downfall. Over time, press reports on the prime minister’s political errors, personal corruption, and abuses of power undermined his popular support, and emboldened the military to step in. By the time of the October coup, Sharif had few friends left. The October 12 coup took place just hours after Pakistan Television announced Sharif’s dismissal of General Musharraf as army chief. Musharraf was on a commercial flight from Sri Lanka at the time; he has accused the prime minister of plotting his murder by preventing the plane, which was dangerously low on fuel, from landing in Pakistan. The plane landed in Karachi only after the army seized control of the city’s airport. On December 8, prosecutors charged Sharif, and six others, with kidnapping, attempted murder, and treason. Clearly, many of Sharif’s press critics would have preferred him to be removed by more democratic means. While General Musharraf went out of his way to say that civil liberties would be respected under his rule, he also made it clear that the press should “play a positive and constructive role.” At year’s end, most journalists, like most citizens, were going along with Musharraf, and the balance of media coverage was overwhelmingly supportive of the army takeover. But some journalists challenged the legitimacy of the coup and questioned the administration’s policies, without apparent repercussions. Still, there have been a few incidents that belied the army’s claims to respect press freedom. A week after the coup, local newspapers reported that the names of 20 journalists had been added to a list of citizens prohibited from traveling outside Pakistan. (Go to footnote 5.) On October 21, a truckload of soldiers visited the Lahore offices of a leftist political weekly, questioned them about their reasons for publishing an issue headlined “No to Martial Law,” and asked for information about the weekly’s publisher and printer. On January 26, Musharraf ordered all high court judges to swear an oath never to challenge decisions made by his administration. Many journalists feared that the general’s next demand might be the unquestioning loyalty of the press. The national English-language newspaper The Nation expressed its fear that the press, which was “similarly promised freedom, could become the regime’s next target.” While Musharraf has announced his intentions to uphold secular values, there are factions within the military and the intelligence agencies that actively support religious extremists at home and abroad. Islamist political groups have retaliated violently when angered by the lack of attention paid by a media outlet or put off by the type of coverage they received. While there have been no serious attacks thus far, journalists know that if they had few protections under Sharif, they have none under Musharraf. The free press in Pakistan has weathered many storms, and should be expected to outlive this regime. But journalists will continue to be vulnerable to political persecution for as long as the democratic foundations of the state remain weak.

|

|

| (1) Local broadcast media are not permitted to produce independent news and public affairs programming, but the increasing popularity of the satellite dish has meant that a growing number of Pakistanis are able to access news produced by organizations such as BBC, CNN, and even neighboring India’s Star TV (owned by Rupert Murdoch). Because satellite television is sometimes watched in communal settings, this is not exclusively an elite phenomenon–though televisions, let alone satellite dishes, remain unaffordable for the vast majority of Pakistanis. Certain programs produced by the BBC are also carried on the state-run broadcast network. (Return to main text) (2) The chief editor and publisher of these papers, Rehmat Shah Afridi, was in fact arrested by Pakistan’s Anti-Narcotics Force (ANF) on April 2, only a few months after Maidan‘s launch. The paper had featured reports about the involvement of ANF officers in the drug trade. Reporters at Afridi’s papers said high-ranking officials in the Sharif administration had told the publisher that he could expedite his release by shutting down Maidan. Afridi was also politically at odds with the Sharif government, and had used his papers to expose the administration’s weaknesses, which, his supporters believed, contributed to his arrest. By December, Afridi was still in prison for alleged drug possession, though no formal charges had been submitted in court. (Return to main text) (3) Shahbaz Sharif was taken into military custody along with others in the administration’s inner circle in the immediate aftermath of the coup. He has been charged with treason and attempted murder for allegedly conspiring with his brother to assassinate Musharraf. (Return to main text) (4) In a remarkable turn of events, the fundamentalist Jamaat-i-Islami party ultimately provided both the printing press and the paper for that week’s issue of The Friday Times. Though the secular ideals and politics espoused by The Friday Times are generally anathema to the Jamaat-i-Islami, its information secretary told the weekly’s news editor, Ejaz Haider, that he supported the paper’s efforts to expose government corruption. (Return to main text) (5) One reporter, a stringer for the American newsmagazine Time, was taken off the list after the weekly published an editor’s note describing his case and asking authorities to send a “signal to the world that, this time, military rule is not the same thing as repression.” (Return to main text) |

|

Kavita Menon is CPJ’s Asia program coordinator. |