Governments use copyright laws and Twitter bots to curb criticism on social media

By Alexandra Ellerbeck

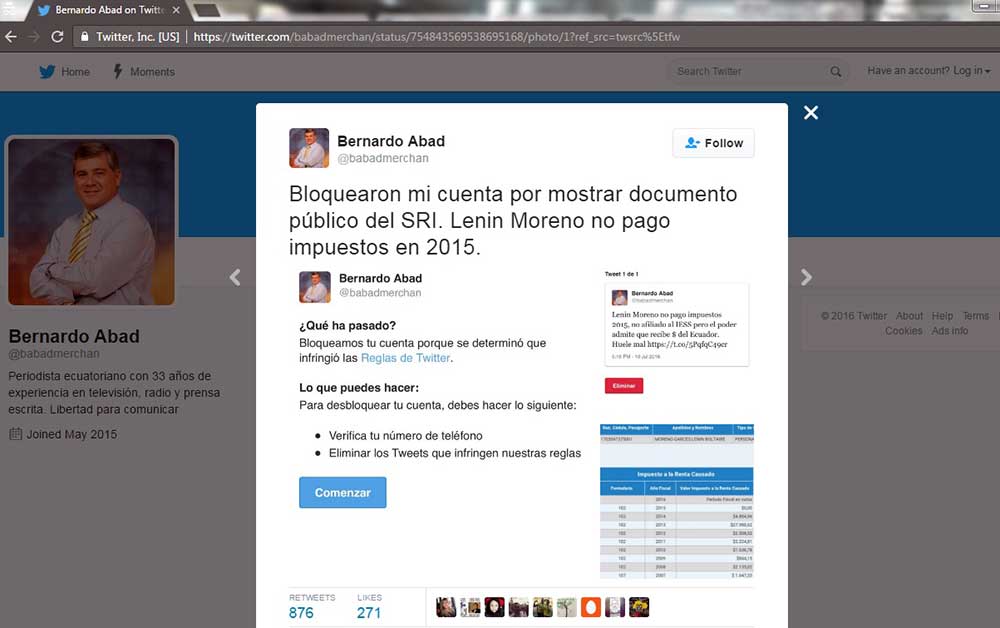

On July 10, 2016, Ecuadoran journalist Bernardo Abad tweeted that the former vice-president of Ecuador, Lenin Moreno, had not paid income taxes for the year before. A week later, Abad received a message from Twitter saying his account had been blocked for violating its terms of service. Within 24 hours, at least five others’ accounts were temporarily suspended after they tweeted about Moreno’s taxes. By the end of the week, nine accounts had been temporarily suspended, according to the freedom of expression advocacy group Fundamedios. Twitter declined to comment on the suspensions.

Free speech organizations have argued that Ecuador’s disappearing content and suspended accounts are the direct result of a government campaign to censor critical information. The groups claim this is part of a broader global pattern – that censoring or drowning out critical voices is no longer the exclusive activity of authoritarian governments such as China and Russia, but is also being done in Ecuador and Mexico.

Moreno, who was lauded for his work on disability rights in Ecuador after he was shot in the back during a carjacking and paralyzed from the waist down, later served as the U.N. Special Envoy on Disability and Accessibility in Geneva. He is the likely candidate to run for president on the ticket of the ruling party after President Rafael Correa’s term ends next year. Much of the Twitter chatter concerned a recent report by the investigative news site Fundación Mil Hojas (“1,000 Pages Foundation”) that revealed Moreno earned more than US$1 million during two years in Geneva when he was working as a special envoy there. Moreno said in a Facebook chat message that the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations exempted him from paying taxes on this money because he was a special envoy.

The nine Twitter suspensions that followed reports on Moreno’s taxes coincided with eight more account disruptions (suspensions or forced removal of tweets) in July 2016 among activists who criticized the government in other ways, according to information provided by Fundamedios. Moreno denied making takedown requests for any of the disruptions, and Twitter did not respond to a request for comment. After Fundamedios, CPJ, and other organizations appealed to Twitter, the accounts were restored.

Ecuadoran free expression groups have long complained that opposition activists and critical journalists risk having their Twitter accounts suspended due to fishy copyright or terms of service complaints. Fundamedios says it documented at least 806 notifications against 292 accounts filed between mid-April and mid-July of 2016, most of them by a single Spanish company called Ares Rights that has routinely filed requests on behalf of Ecuadoran government agencies or politicians.

CPJ has been unable to independently verify those numbers, but reports of censorship on social media have been widespread in Ecuador. In 2013, Buzzfeed received a copyright notification from Ares Rights filed on behalf of Ecuador’s National Intelligence Secretariat after the media outlet published leaked documents alleging that the agency had purchased surveillance equipment. Ares Rights has also filed a number of takedown requests on behalf of the Ecuadoran Secretary of Communications (SECOM) against free speech organizations and opposition media outlets, despite the fact that the government agency has denied any contractual relationship with the company in the past. SECOM did not respond to requests for comment.

During the Arab Spring six years ago, social media was seen as an organic expression of popular opinion that was capable of undermining governments and sparking revolutions. While the narrative of the social media revolution has become complicated in the years since, the general idea was, and in many places still is, that social media provides a snapshot of the public’s conversation. It is this assumption that leads to controversy when social media platforms step out of the background and appear to exert editorial influence.

But it is not just the platforms that are influencing content: The governments that these networks of citizen journalists were supposed to check have become increasingly sophisticated in using social media for surveillance, censorship, and propaganda. Governments and high-profile political figures are, for better or worse, increasingly shaping the debates taking place on platforms like Twitter and Facebook, whether through armies of propaganda artists in Russia, China, and Mexico, the surveillance and removal of accounts as part of the United States’ counterterrorism efforts, or the suspension of critical Twitter accounts in Ecuador.

Twitter publishes annual transparency reports about the number of takedown demands the company receives from government agencies or courts throughout the world. Between January and June 2016, those reports found that Russia had 1,601 requests, Turkey had 2,493 and the U.S. had 100, though Twitter said it did not comply with the vast majority of the removal requests. Ecuador only had one request, with which Twitter said it did not comply, in contrast with the frequent complaints of allegedly politically motivated copyright and privacy violation complaints, which are harder to detect or to link directly to the government.

***

On December 1, 2014 journalist Erin Gallagher was blogging about a major protest in Mexico City. She had been following the case of a group of missing Mexican students since September 26, 2014, when the 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College disappeared on their way to a protest in the capital Mexico City. A flawed investigation, and indications that the military might have been involved, stoked existing frustrations with violence and corruption in the country and sparked a series of massive protests. Gallagher covered the demonstrations remotely from her home in Pennsylvania for the website Revolution News by talking to activists and following social media. She said she was following the protest-linked hashtag #RompeElMiedo (“Break the Fear”), when something strange happened.

“I had been following the protest live all day long and into the evening, and then all of a sudden the hashtag I was following was flooded with spam,” Gallagher said. “When you run into it online in real time, you know that there’s something strange happening. It’s obvious that it’s not organic information.” Posts connected to the hashtag were filled with nonsense, random words or symbols, to the point that it became unusable.

Gallagher said that she realized she had run into political bots — automated social media bots programmed to influence online discussions. Researchers who study online bots confirm that there is evidence that trolls or bots manipulate social media in Mexico in order to change trending topics, threaten journalists, push out propaganda or divert online discussions that are critical of certain political figures.

“I would say that Mexico is the benchmark for the worst and most manipulative use of bots,” said Sam Woolley, the project manager of Politicalbots.org. “Bots are used as a roadblock,” he said. “A bunch of information would be tweeted at activists with the goal of disrupting conversations or having a chilling effect.”

Nicknamed Peñabots for their tendency to send messages in favor of Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto or his party, experts told CPJ that bots were now being used by all political factions in Mexico. Gallagher said the general assumption that bots are active in Mexico’s political discussions is so widespread that some legitimate expressions of support for the government may be mischaracterized as spam.

Bots are not always easy to identify. Although there are some indicators, such as the frequency of messages, the coherence of messages, and the relationships between bots, it can be hard to definitively identify automatic accounts, especially for casual observers. And bots are becoming increasingly sophisticated. “For any detection system you write, I can write a bot that gets around it,” said Tim Hwang, a researcher at the New York City-based research institute Data and Society. “I think it will be an arms race. Campaigns of manipulation will get more sophisticated.”

In Mexico, Woolley said that it is increasingly common to see bots combined with human commentators. A bot account might initiate a discussion, but then a human will take over if anyone else becomes engaged in a back-and-forth.

Hwang and Woolley are both quick to point out that politically oriented bots are not always bad. They can be used to connect political activists, provide information, or track incidents. For example, there is a bot that tracks every shooting by a police officer in the United States. Still, they are subject to being abused.

Even harder than identifying political bots is figuring out who is paying for them and where they come from. In March, Bloomberg cited jailed Colombian hacker Andrés Sepúlveda as saying he was hired by Peña Nieto’s campaign for president in 2012 and that one of his tasks was to manipulate online opinion by managing fake profiles and an army of 30,000 Twitter bots. Although Bloomberg said that parts of Sepúlveda’s narrative coincided with technical attacks and propaganda that took place during the election campaign, not every detail of his story was independently corroborated. The Office of the Presidency did not respond to requests for comment.

Political manipulation is hardly centered in Ecuador or Mexico. A survey of 65 countries in the 2015 edition of Freedom House’s report, “Freedom on the Net,” found that 24 of them employed the use of pro-government commentators to manipulate discussion. In China, a group of government workers known as the “Fifty Cent Party” posts pro-government propaganda and coordinates smear campaigns against critics, while armies of government-linked commentators have viciously attacked journalists in Russia. Even the United States has researched social media manipulation for counter-terrorism efforts.

Manipulation is also not limited to Twitter. Woolley and Hwang said there are bots and paid trolls on Facebook and other platforms as well. The open structure of Twitter simply makes it easier to detect.

For journalists, manipulation of social media means that some discussions are lost while others are added under false pretenses. These are difficult territories to chart. Even as Ecuadoran journalists persistently republish, again and again, censored content, and Mexican journalists soldier on in the face of trolling and threats, governments and political operatives continue to expand and adapt their efforts to thwart public debate and opposition.

Alexandra Ellerbeck, CPJ’s senior Americas and U.S. researcher, previously worked at Freedom House and was a Fulbright teaching fellow at the State University of Pará in Brazil.