Late on the evening of September 16, 2000, 31-year-old Ukrainian investigative journalist Georgy Gongadze left a colleague’s house in Kiev and headed home to where his wife and young daughters awaited him. He never made it.

“Those first couple of days were really blurry,” his wife, Myroslava Gongadze, recently recalled. “I was in a sort of limbo and didn’t know what to do.” Days after her husband’s disappearance, local officials ruled out a political motive despite his sharp criticism of the Ukrainian government. In mid-November, a burnt, headless body was identified as the journalist’s, and within weeks, an opposition leader leaked taped recordings of what appeared to be conversations between then-President Leonid Kuchma and other high-ranking officials on possible ways of “dealing” with Gongadze. So Myroslava Gongadze, a lawyer by training, decided to step in. If she, who was so personally affected by the murder did not take the lead, she said, no one else was going to fight for the truth.

Using her legal knowledge, a network of media contacts and a steadfast drive, Gongadze worked with a group of local and international journalists and human rights organizations to build a legal case and a public campaign. Fifteen years on, four former officials have been convicted of murder while the European Court of Human Rights has ruled that the Ukrainian government is liable for the journalist’s death. Despite her success, Gongadze says that there have been times when she has been ready to quit. “I have wanted to change my name, to disappear, to change my life, to become a different person. And then I realize that this is it. This is me.”

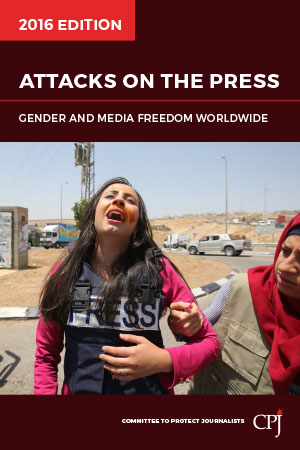

Since I began working for the Committee to Protect Journalists in 2005, I have met and worked with a number of other women from around the world who, like Myroslava Gongadze, have become prominent figures in press freedom campaigns. They are the mothers, wives, daughters, sisters, girlfriends, and colleagues of journalists who go missing, are held hostage, injured or imprisoned, or who have been killed. Though they have male counterparts, a majority of the impromptu campaigners that I have encountered are women. They come from different countries and backgrounds, while their individual battles are strongly rooted in personal stories. Yet they share an unrelenting commitment to truth and justice that transcends those particular experiences.

Is gender the root of their commitment? The frequency of cases such as Gongadze’s would seem to point in that direction. But in speaking with her and others who have waged similar fights, gender seems not to play a predictable role. The women recognize a pattern, but they also raise contradictions in their analysis of what has driven them to the forefront of campaigns in some of the world’s most visible attacks on journalists.

In November 2015, I interviewed four women whose lives were fundamentally transformed by a single devastating event that, within days–hours in one case–had turned them from wife, mother, or friend into a kind of combatant. My goal in interviewing them was to dissect battlefield stories and strategies in order to understand the role that gender had played. I spoke with Gongadze; with Sandhya Eknelygoda, wife of missing Sri Lankan political cartoonist Prageeth Eknelygoda; with Diane Foley, mother of American freelancer James Foley, who was taken hostage and brutally murdered in Syria; and with Soleyana S. Gebremichael, a founding member of the Ethiopian Zone 9 bloggers collective, several of whose colleagues spent more than a year in jail.

Of the four, only Eknelygoda told me that gender was key to her struggle. The other narratives were less clear-cut. Foley and Soleyana both said gender does not drive the kind of battle they have waged. Temperament and commitment do. In fact, Foley said, her son “is the hero. Jim is the one who keeps me going,” adding that she developed a passion for justice from him.

For Gongadze, it is not the fighters’ gender that is at play, but rather the gender of those on whose behalf they are fighting. “I guess it’s mostly the men who are journalists who get into danger,” she said. The numbers CPJ collects on journalist murders support that assertion: Of the 1,175 journalists killed since CPJ began tracking these cases in 1992, 93 percent were male. “Then who is left to fight for them?” Gongadze asked, answering almost immediately: “Their women.”

When Prageeth Eknelygoda, a fierce critic of the government of former Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa, failed to come home on January 24, 2010, a few days before the country’s presidential election, Sandhya Eknelygoda rushed to the local police station to report him missing. Officers laughed at her, saying he was probably with another woman or had staged his own disappearance, Eknelygoda said, but she persevered. Later that month, she met with the senior superintendent of police, and when he, too, dismissed her concerns, she filed a complaint with the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka. Faced with silence, Eknelygoda began to write letters to high-ranking officials. When those went unanswered, she filed a habeas corpus asking for Prageeth’s whereabouts or for his body. And when this effort also failed, Eknelygoda reached out to the international community and began a series of public appearances around the world to highlight her husband’s case.

In January 2015, Sri Lanka held early presidential elections and the opposition candidate, Maithripala Sirisena, surprisingly defeated Rajapaksa, who was seeking a third term. By this time, Eknelygoda’s quest had blown up into a global mission for truth not only for her husband and other journalists, but also for thousands of disappeared Sri Lankans for whom she has become a de-facto spokeswoman. Almost immediately after being elected, Sirisena pledged to reopen the files of missing and killed journalists, and by the time I spoke with Eknelygoda in 2015, five army officers and two civilians had been arrested in connection to Prageeth Eknelygoda’s disappearance.

Armed men kidnapped Jim Foley, an American freelance journalist, in Syria on Thanksgiving Day as he was making his way to Turkey. His whereabouts were unknown until August 19, 2014, when the militant Islamic State group posted a video online showing the journalist’s brutal beheading as a warning and reprisal of the government of U.S. President Barack Obama. At the request of Foley’s parents, Diane and John Foley, his disappearance had not been made public until January 2013, when they launched a vocal campaign seeking his release. Almost immediately, Diane Foley became a voice for the families of other American hostages.

After her son’s brutal killing, a devastated Foley decided that she would not give up her fight. “I could not let someone so extraordinary die,” Foley told me over the phone on her way home from Washington, D.C. after having testified before the U.S. Congress. Within three weeks of her son’s murder, she had filed the necessary paperwork to start the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation, which champions causes that her son was passionate about: support for American hostages, greater rights for freelance journalists, and better education for underprivileged youth.

So far, Foley and her foundation have had a hand in important changes to two of these three issues. In February 2015, a coalition of news executives, press freedom groups and individual journalists, including CPJ, agreed to a set global principles for freelancers’ safety. To date, the principles have been signed by 78 organizations. Four months later, the Obama administration announced changes to U.S. hostage policy. According to news reports, the change in policy will allow government officials to communicate and negotiate with groups holding hostages and help American families seeking to do the same, while an interagency hostage recovery “fusion cell” will coordinate efforts to free American captives. Though encouraged by the progress, Foley says she will only believe there has been real change when an American hostage has come home.

* * *

Ethiopian authorities in Addis Ababa rounded up six young bloggers who were part of an independent collective know as Zone 9. On that day, Soleyana, one of the group’s founding members, was traveling outside the country. From Nairobi, Kenya, Soleyana stayed informed of the day’s events in real time through her friend and colleague Zelalem Kibret, until he, too, was detained. That evening, having reached each of her friends’ families by phone, Soleyana worked with Zone 9 cofounder Endalk Chala, who was also abroad, on a press release calling for the government to release their colleagues from prison, she told me from her new home in Maryland. She said they subsequently launched a formidable social media campaign with the hashtag #FreeZone9Bloggers.

In July 2015, more than a year after the Zone 9 arrests and weeks before President Obama visited Ethiopia, Ethiopian authorities released two of the bloggers. Three months later, the rest were freed. In November, CPJ awarded Zone 9 with an International Press Freedom Award.

Soleyana and the other women I interviewed had a clear goal from the beginning, but their campaign strategies, they told me, have been built ad-hoc. The week after her husband’s disappearance, with no action or clear answers from local authorities, friends convinced a disoriented Myroslava Gongadze to hold a press conference. Accompanied by her four-year-old twins, Gongadze told journalists that her husband hadn’t come home. She then voiced a call to action. “I said that they needed to support me; that the journalistic community needed to support me. I said it’s him today, you tomorrow,” she said. “But there was no real strategy until I realized that there was not going to be justice in Ukraine. Then, I had a strategy and I called for a special investigation with support from [the International Federation of Journalists, Reporters Without Borders] and CPJ. We did reports on the progress of the investigation. And we analyzed all the possibilities for international justice.” Gongadze eventually filed a suit with the Strasbourg, France-based European Court of Human Rights, claiming the government had failed to protect her husband and to properly investigate his murder. In 2005, the court found the Ukrainian government liable for Georgy Gongadze’s death and awarded his wife 100,000 euros, about U.S. $118,000 at the time, in damages.

Media attention, whether intentional or impromptu, good or bad, has also played a pivotal role in these campaigns. Charismatic in their own way, each woman has found and fostered an intricate relationship with the media. For Gongadze and Eknelygoda, their husband’s colleagues have been crucial. Local journalists, they told me, have been among their closest allies, while local and international media have helped not only broadcast their calls for justice, but have continuously highlighted their work.

“There are many sympathizers to my work in the media, and of course there are others who are not cooperative,” Eknelygoda told me via Skype from her Colombo, Sri Lanka kitchen with her teenage son acting as our translator. “But I have many friends in the media who understand me and give publicity to Prageeth’s case. There is a lot of support for me as a person and for the cause that I am fighting. There is also comfort and satisfaction in the fact that the media continue to be sympathetic. It is so important to give the case exposure in the media.”

Soleyana’s case is a little different than the others in its approach to the media. For most of the 18 months that her six friends spent in prison, Soleyana worked with two other bloggers–Endalk, who lives in the U.S., and Jomanex Kasaye, who managed to escape Ethiopia and has since settled in Sweden–publicizing the case mostly on social media. “Our strategy was to highlight the journalists as human beings: family members, friends, etc. –not as politicians,” she said. “We wanted to show their human side, and we used social media to tell their stories so that other young people in the country could relate to them.” The end goal of their social media campaign, Soleyana said, was to keep the international community and the Ethiopian public informed and engaged in their calls for the bloggers’ release.

Though Soleyana says responsibility for the campaign, like the blog that led to the imprisonments, was shared with Endalk and Jomanex, Endalk said Soleyana’s charisma helped make a strong yet likeable public case for the release of their colleagues. “She is happy to engage anyone online or offline,” Endalk said. As part of her strategy, Soleyana also highlighted the Zone 9 case at meetings with international groups and high-ranking officials, including Obama and U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry.

In Endlak’s view, Soleyana was the force that kept the group going. “Gender is very important and I think it is directly related to her role in the blog and the campaign,” he told me. “Before we even started, before the arrests, Soli was very good at organizing stuff and she had a very important leadership role in putting the group together. She is so demanding and her standards are so high, she is always asking us to produce things. Even when we remind her that this is voluntary work, she keeps pushing. And this role continued after the arrests.”

Despite growing external strategic support, which Gongadze, Eknelygoda and Soleyana credit as necessary to their success, their campaigns could not have survived the long haul without what is best described as a kind of religious devotion on their part. When I asked Gongadze how she referred to the work that she had been doing, she said: “Finding justice for Georgy was just my life. I had no name for it.”

All four women said they were driven by devotion, passion and strong personal feelings–concepts that are hard to define, as Gongadze told me. The role of gender is likewise difficult to gage. Foley noted that women can be very passionate, “but so can men.” Eknelygoda insisted that, “women feel a different way about relationships than men do. There is a clear difference in the way in which men and women even think about these situations. Men tend to give up after some time, but women continue to fight.”

The fight itself, regardless of what drove it, has exacted a toll on all of them. Eknelygoda and Soleyana quit their jobs almost immediately to devote all their time to the campaigns. In both cases, this decision meant having to rely heavily upon external financial support. Soleyana said she had to apply to international organizations for emergency grants, which she administered, to pay for campaign costs and basic needs for the families of those who were imprisoned. Eknelygoda received similar support, but financing her years-long campaign while supporting her family, she told me, echoing Gongadze, has made a difficult road to justice even harder.

Some of her greatest difficulties have been financial, Eknelygoda said. During a 2012 interview, a clearly pained Eknelygoda had told me that fearful friends and family had abandoned her and her two sons after her husband’s disappearance. Having quit her part-time clerical job and lost her husband’s income, she was forced to turn to donations from concerned individuals and to emergency support from international organizations, including several grants from CPJ’s Journalist Assistance Program. In 2015, as the legal case continued to require most of her time, Eknelygoda said she was paying her bills through the proceeds from a small catering business that provides what she calls rice packages at small events, allowing her to continue devoting most of her time to her activism.

There have been other bumps on the road, she said. Perhaps the roughest, which have shaken her to the point of questioning her devotion, have come at the hands of local authorities who until recently ignored and disregarded her systematically while countering her campaign with unsubstantiated claims. In 2012, then-Attorney General Mohan Peiri told United Nations officials that Prageeth Eknelygoda was hiding in a foreign country and that the campaign to solve his disappearance was a hoax. Six years on, the pain associated with financial, political, and social isolation remains raw for Eknelygoda.

Stories like Eknelygoda’s–of degradation at the hands of local authorities–are not uncommon. In my 10 years of reporting on press freedom violations, I have repeatedly been told of similar disregard for family members, many of them women, who are seeking support or information about a loved one. This group includes Gongadze who, recalling the day she reported her husband missing, said local police officers “were just laughing at me, telling me to go away.” With a knowing smile, she said officials told her that her husband probably left her for another woman.

Part of Diane and John Foley’s decision not to make their son’s disappearance public until January 2013 was based partly, Foley has frequently said, on encouragement from the Obama administration to remain quiet in order to protect her son. “I trusted much too long and we failed. We were duped,” Foley said. According to her, authorities failed to conduct a proper and timely investigation into her son’s kidnapping; gave her and her husband little or misleading information about their son’s situation; and refused to negotiate with her son’s captors while warning her and her husband that they could face prosecution if they paid the ransom. “Though I do not blame anyone,” she said, “we did let policy get in the way of helping.”

Despite her disclaimer, Foley feels that the government failed her son, and that so did the media and organizations dedicated to protecting journalists, including CPJ. She believes that despite the initial media blackout, people active in the field could have more actively supported her quest. “Jim had vanished and a lot of journalists knew war zones and knew Syria. They could have helped because they knew more than the government, but they didn’t call us. They never come forward with information,” she said. As Foley explained her attempts at accountability, it was apparent that she felt a deep sense of isolation rooted in her campaign–not dissimilar to the feeling Eknelygoda also described.

Beyond personal hardships, these women shared other considerable obstacles. Most notably, they have all faced direct threats. Since going public with her quest for her husband’s whereabouts, on several occasions Eknelygoda has received phone threats from unidentified individuals who accuse her of being a traitor. Foley said she has been harassed on social media by people who consider her open criticism of the U.S. government an attack on the American way of life. Both have been shaken, but neither has considered the threats serious. The threats against Gongadze and Soleyana, on the other hand, forced them into exile.

“Right away I started to receive threats,” Gongadze said. In the months after her husband was killed, Gongadze became aware that her every move was being tracked, she told me, adding that he too had been trailed.

Colleagues with connections to Ukraine’s security apparatus, Gongadze said, told her that her phones had been tapped and warned her not to discuss anything important. “So, at that point, I sent my girls to live with my parents,” she said. “I asked a friend to take them, and nobody knew where they were. They had taken my husband and I did not want my kids at risk because I had decided to go public.”

Then, Gongadze said, a local politician handed her an alleged recording of President Kuchma telling his chief of staff to do something to stop her and the editor of Ukrainska Pravda, her husband’s outlet. In the recording, the man purported to be Kuchma urged the other official to stop Gongadze’s activities, which he said had become a nuisance, she told me. Though Gongadze says she did not know how the recordings were made, she began to seriously fear for her life and that of her children. A member of the opposition had earlier leaked another set of secretly recorded tapes in which Kuchma, who served as president of Ukraine from 1994 to 2005, is overheard plotting with other high-ranking officials, including his chief of staff, on different ways to get rid Georgy Gongadze. Kuchma was indicted in 2011 on abuse-of-office charges related to the Gongadze case, though he rejected accusations that he had a role in the journalist’s murder. However, according to press reports, he did not deny that the voice in the first set of tapes was his, though he claimed the recordings had been doctored.

Gongadze and her daughters left Ukraine for the United States, where they were granted political asylum in 2001.

Soleyana also traveled to the U.S., leaving East Africa a month after the April 2014 Zone 9 arrests. Until then, she had remained in Nairobi, Kenya, where hundreds of other exiled Ethiopians, including dozens of journalists, live. Fearing the long arm of the Ethiopian government, Soleyana and Jomanex, who had fled on the night of the arrests, decided to leave East Africa.

Soon after Soleyana left the region, her mother’s Addis Ababa home was raided in what she described as a fruitless effort by Ethiopian authorities to find solid evidence linking Zone 9 to terrorist organizations. Despite a lack of evidence, in July 2014, an Ethiopian court charged Soleyana with terrorism in absentia. She was acquitted, also in absentia, a year later. “At that point,” she said, “it became clear that I was not going to go home.”

Self-imposed exile has given Gongadze and Soleyana the security and space to continue their work. Leaving Sri Lanka for short periods of time and speaking publicly at the international level has also given weight to Eknelygoda’s campaign and, in a way, afforded her protection. Eknelygoda is now an award-winning international figure who can open doors that six years ago would likely have been slammed shut.

The quest for justice has become so entwined with all the women’s lives and identities that even after some form of resolution, they continue to define themselves through their quest. In all four cases a commitment that began as personal has developed into a mission for justice and greater change.

Despite the shift in the campaign, and in the way that she is perceived, Eknelygoda sees her new goal and role as an extension of the mission she set out on the day her husband did not come home. “When I was fighting individually [for Prageeth], what I determined first was to not let the case of a disappearance be disappeared,” she said. “Now I work to represent the voices of the voiceless using my voice. Those are the reasons that I am where I am now.”

Asked about her husband’s possible fate, Eknelygoda said she fears she will never know the truth, but that she finds solace in knowing that her continued advocacy will in some way keep him alive. “Whatever they say, whatever the truth is, he is alive for me, he is alive in my fight,” she said.

María Salazar-Ferro is CPJ’s Journalist Assistance Program coordinator. She covered the Americas region for CPJ for four years and has written reports on exiled and missing journalists and impunity in journalist murders. She has represented CPJ on missions around the globe.