As a child, I never thought about becoming a journalist. I never really felt pulled toward any particular field. I just loved to feel free and try new things, especially when it came to hard work.

I had just finished my final examinations in July 2007 and was preparing to get a bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Baghdad University when I got a phone call from a friend of mine who worked as a journalist in Baghdad. My friend told me there was a good job opportunity with The New York Times. I didn’t know much about the Times; I wasn’t a big fan of watching news on television and the paper itself had never circulated in Baghdad.

But I liked the idea of being a journalist because it meant that I could practice my English with native speakers again after working for the U.S Army for nearly two and a half years, from 2004 until 2006.

On a hot day in mid-July 2007, I met one of The New York Times‘ correspondents along with my friend, who knew him through her work as a journalist. Stephen Farrell is an enigmatic character full of energy–he drinks Red Bull more than water. Mr. Farrell helped me and guided me, but sometimes my stubborn mind wouldn’t comply. I think it was the cultural gap between us; it takes a long time to understand somebody’s culture.

The meeting that day was in what was supposed to be one of the safest places in Baghdad: the Palestine Hotel. The room was gloomy, but I was optimistic about this new job. Farrell looked satisfied with my qualifications, and I felt very proud to be considered for such a position at the age of 20. I was able to do multiple tasks; translating, reporting, and writing in one job.

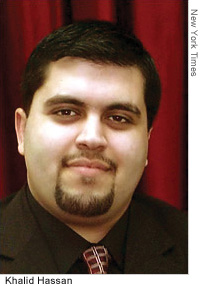

I started work a couple weeks after that interview. As I walked to the front gate of the bureau, I noticed a black banner that marked the death of an Iraqi journalist for the Times who had been shot by gunmen near his home while heading to work. Khalid Hassan was 23, only three years older than me. I had to wonder what fate seemed to be telling me as I walked into the bureau. “I’m here to replace a dead journalist nearly my age. Am I next on the list?” I was thinking as I inspected the new place and the pale faces around me.

Over the next few days, I found myself watching Arabic television news that and translating reports for the Western staff at the bureau. I was learning and, most important, trying to control myself when I was angry because a journalist needs forbearance, especially in Iraq.

I felt that I should do more than sit in the bureau watching and translating the news behind a computer screen. I thought I might learn more as a journalist and as an Iraqi if I could go out more and report from the street. I started to track the deaths in my city–there were too many explosions. I was trying to convey the truth to the whole world and find the answers to my questions about who was behind those explosions; I never found a clear answer.

One day, an explosion ripped through Sadoon Street in central Baghdad. It wasn’t far from our bureau so I accompanied Michael Kamber, an American photographer with The New York Times, to the site. In these situations, you have to deal with angry people, stupid security forces, or the possibility of a secondary explosion, in addition to many other things.

Iraqi police forces and American soldiers were all over the place. We parked 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) from the explosion site and walked the rest of the way. No civilians or pedestrians were allowed to wander around; we as journalists would face many difficulties in getting such permission as well. Mike found his way to the Americans while I talked to Iraqi eyewitnesses.

After I finished with the witnesses, I tried to make my way to Mike, but the Iraqi police blocked me even though I told them I was a journalist. I tried to go through anyway, but a police officer punched me in the face. I punched him back. I found myself in the middle of the other Iraqi police officers who were trying to beat me without knowing who I was and what I was doing there. It stopped only when Mike told the Americans that I was with him. One of the soldiers grabbed my shirt and pushed me away from the Iraqi police officers. The Iraqis couldn’t do anything more once the Americans intervened.

At the Times building in Baghdad, I found another family. It was like a small Iraq: Iraqi Shiites, Sunnis, and Christians worked together with Westerners in peace. I was always hoping to have the same life in Iraq, with people getting along and living in peace.

As an Iraqi journalist working with foreigners, I felt a big burden–I was responsible for the whole crew of drivers, local guards, and journalists. In my job, I would deal with militants or even insurgents. I had to be very careful. I had to learn what I should say, how I should say it, and what I shouldn’t say.

People on the streets were another obstacle. One day I visited a mosque just a few feet from our bureau with Johan Spanner, a Danish photographer for the Times. I could sense that the sheikh of the mosque wasn’t comfortable with our being there. “Why aren’t you pleased with our presence?” I asked.

He replied: “I know who you are and I know what you want. You are here with some Jews looking for trouble.” I got very angry at the sheikh and kept explaining who we were and what we wanted. We just wanted to photograph children being taught the Quran at the mosque. Johan admonished me later for being angry at the sheikh; he was right, because in some places that anger would cost you your life.

I lived this double life for almost two years. I couldn’t stand it anymore because it’s not only dangerous but a lot of people don’t appreciate what you do or don’t understand it. Yet I learned many things about teamwork and responsibility. The worst part was witnessing the death of many of my own people. I saw death in so many ways that I wasn’t afraid of it at all; in fact, I was tempting death through my job.

Coming to America is another chapter of my life. Here I am in Tucson, looking for a job and adjusting to the American style. I sometimes feel like an old veteran who needs nothing from his life but relaxation. Other times I yearn for action and excitement. I’m not staying here forever, but I’m going back to Iraq only when there are no Iraqi or American soldiers on the street at all.

Mudhafar al-Husseini worked at The New York Times in Baghdad for two years, reporting news stories and writing blog entries as well as acting as a fixer and translator for other reporters. Before that, from 2004 to 2006, he was a translator for the U.S. Army in Iraq. He graduated from Baghdad University in 2007 with a degree in English literature. Now living in the United States, he is updating us on this new chapter in his life.

Read al-Husseini’s previous entry here. To read all his “Finding Refuge” entries, click here.